In late 2017, actor Justin Baldoni summoned his courage and opened his heart, taking to the TED stage to deliver his talk on redefining masculinity. He used the platform to honestly examine the pressures that he has felt since childhood, and how they have impacted his life, often for the worse.

“I’ve been pretending to be a man that I’m not my entire life,” he said. “I’ve been pretending to be strong when I felt weak, confident when I felt insecure and tough when really I was hurting.” A self-proclaimed feminist, Justin then laid down a challenge for men, “Are you brave enough to be vulnerable? Are you strong enough to be sensitive? Are you confident enough to listen to the women in your life?”

Justin initially rose to fame by portraying heartthrob Rafael Solano in the CW satirical romantic dramedy ‘Jane the Virgin.’ And in a career trajectory has taken him from half-dressed hunk, to bonafide film director, activist and business entrepreneur, Justin is the master of his own ship, navigator of his own course. The Ted Talk has been viewed almost ten million times, and Justin’s candor has propelled him onto a purposeful new path. His three million-plus social media followers are now engaging in this much-needed conversation around masculinity, in which he has become one of the leading modern, male voices.

Now, nearly three years on from that life-changing talk, he releases his equally fearless book, ‘Man Enough: Undefining My Masculinity’, on April 27. Here, he exercises absolute transparency and reveals his fears, struggles and insecurities. No topic is off limits, and the revelatory book covers tough subjects like pornography, white privilege, bullying, and being objectified in his acting career (and that’s just for starters). Justin walks that fine line of triggering the male reader, whilst deftly encouraging us to stay with that feeling, exercise self-awareness and do the necessary work. He promotes – and lives – a life of being “comfortable with the uncomfortable.” For someone who looks to have it all on the outside, ‘Man Enough’ intimately exposes us to the depth and breadth of this perfect-looking man’s anxiety up close, and thus inspires us as readers to examine the hard truths of our own conscious and subconscious behavioral patterns.

‘Man Enough’ follows on the heels of a web-based show of the same name, where Justin hosts heart-to-heart conversations with other men from all backgrounds, their intention being to undefine the traditional roles and traits of masculinity, thereby allowing men to realize their potential as humans and their capacity for connection. Justin succeeds in presenting an elegant case on a provocative subject marred in centuries of conditioning, whilst prompting questions that wake us up to the work necessary to living an authentic life.

Previously to this work around masculinity, Justin had already shown his dedication to telling important, impactful stories. He created and directed the award-winning documentary series ‘My Last Days’, which is a moving show “about living, told by the dying,” and directed two thought provoking feature films in the last two years, ‘Five Feet Apart’ and ‘Clouds’. He’s also co-founder and co-chair of Wayfarer Studios, which produces purpose-driven content, and the Wayfarer Foundation, launched to bring love and compassion to people experiencing homelessness.

He is also a husband, a father-of-two and a man of deep faith, namely the Baha’i Faith, a new religion born in the 19th century. Its tenets take their lead from teaching the essential worth of all religions, the unity of all people, explicitly rejecting racism and nationalism. At the heart of Baha’i teachings is the goal of a unified world order that ensures the prosperity of all nations, races, creeds and classes.

Mr Feelgood co-founder John Pearson sat down with Justin to discuss his journey from TV heartthrob to becoming an author and a bold contemporary pioneer demystifying masculinity; how he tackles and faces his fears, and what changes men can commit to in order to create a better future.

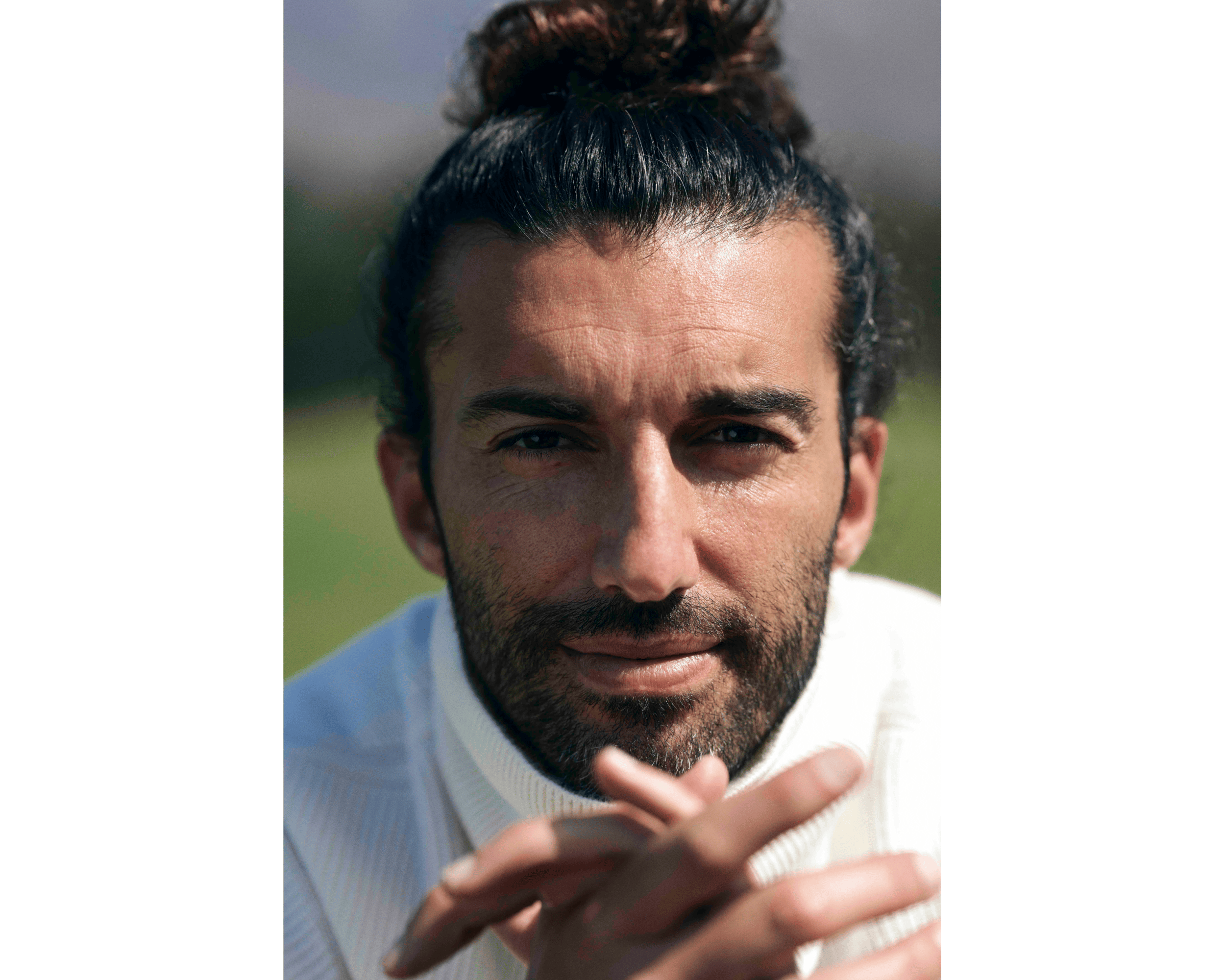

Justin Baldoni // 📸: Kurt Iswarienko

We’re very inspired by you and your story as a family man and a modern man. What inspired you to tackle the masculinity issue as the subject of ‘Man Enough’? Was there a particular event or catalyst, or how did it come about?

It was not one event, it was all events. I think it was my life, a combination of a lot of things. It’s a combination of growing up and being behind, skinny, shorter and not ‘alpha’, whatever that means. And then having athletic ability, getting stronger and bigger, and still not being accepted by the very guys I wanted to be accepted by. Trying to figure out how to be with women and whether or not I should be who I really am — which is sensitive and rather emotional — or if I should be tough and stoic, and what’s going to make women like me. Then it’s trying to figure out in success: Who am I? Am I somebody who needs to walk all over somebody to get ahead, or am I a servant leader?

Putting on all these different outfits and masks and trying to figure out which one I am, all the while not feeling like I’m any of them. It was all of those things together, basically what every man goes through, but not every man admits.

It’s constantly looking out at the external world feeling like you’re not enough, you’re less than, you’re not doing something right. You’re not this enough or that enough, versus just looking in the mirror and recognizing that who I am, as I am, is enough. Why can’t I accept that? Why can’t I be that? What are these invisible forces that are making me talk over women or doubt myself or puff out my chest when I’m around certain people? It was all of them together.

I think that, coupled with my faith, growing up as a Baha’i, being encouraged to question and ask questions about everything, the independent investigation of truth, which is something we believe in. My spiritual values, understanding that I have a body but I’m not my body. I think it was an amalgamation of a lot of things. As I asked questions, I looked and realized that masculinity was a part of it, and I wanted to talk about it.

Justin Baldoni // 📸: Kurt Iswarienko

How will all your research, your learning, affect the way you raise your son and your daughter? How does it inform that?

I think every time you learn something, you become aware, right? You’re only responsible for what you know. For me, I’m becoming aware of a lot, so the bar is becoming much higher day by day of the kind of man I want to be, the kind of children I want to raise. What I try to do is, as I learn something or I’m educated by something or I’m given feedback by someone — mostly women in my life — I try to implant it here in my heart, and then do what I can to practice putting that into action.

It’s as simple as if I recognize that I have a resistance to doing the laundry, then I need to try to figure out why, and at the end of the day, just do the laundry. It can be that simple. If I recognize that I tend to interrupt women or talk over my wife, then I need to then make more of an effort to not, and then if I do do it again, to immediately apologize and say, “Oh, I did it again.” It’s just being aware. Once you’re aware, you have a responsibility, and it’s your ability to respond to the thing.

Justin Baldoni with wife Emily

How do the teachings of your Baha’i Faith deal with masculinity and why is it so relevant right now, in this time we’re living in?

In the Baha’i Faith, masculinity isn’t so much tackled per se, but there’s a lot of very interesting writings that really make you think and question. As an example, in the Baha’i Faith we’re told that if you have two children, a boy and a girl, but you can only afford to educate one, then you educate the girl, because if you want to change the world, then it starts with the education of women. As a man, we’re told that the equality of women and men are like two wings of a bird, but it’s not until those wings are truly equal that the bird can fly. We’re told that it’s not until women have achieved true equality in all arenas of life that humanity can ever find peace.

In terms of masculinity, you look at that and you go, ‘If the system that’s in place is telling me that I’m getting all the opportunity and that women are not truly equal, even if it appears that we are or even if people are saying that we are, then spiritually I have to look at how I’m contributing to that or how I’m benefiting from it.”

Baha’u’llah also says that we’ve been living in a masculine age, but the future will be much more permeated with feminine ideals. It’s debatable what is feminine and what is masculine, but I think he was just speaking to what we consider feminine and masculine, because you have to talk to the person where they are. What we consider masculine is strength and toughness and rigidity and force, right? Power. What we consider feminine today are qualities like compassion and empathy and patience and kindness, even though we know that those should be masculine qualities as well.

What he’s saying is that the future will be an age more with the qualities of compassion and kindness and love and empathy, these things that women tend to be a little better at than men, if you look at the whole. I’m not saying that men don’t have these qualities or that men don’t have them at birth. I think we’re just taught to not have them, and women are taught and reinforced to have them.

Justin Baldoni // 📸: Kurt Iswarienko

On your travels and your journey and through what you’re contributing to culture and society, have you noticed men’s views on masculinity changing? If so, when and how?

Yeah. I think what I’ve learned, and one of the reasons why I ended up writing the book, was after my TED Talk went fairly viral, I noticed that women were publicly sharing and commenting on it. Men were publicly bashing it, but privately writing me. We have this thing where it’s like we want to change, but we don’t know how. We want to be open to things, but we can’t be publicly open to things because that then will be looked at, and that thing will define us. We’re afraid of losing our standing.

I believe men want to be vulnerable, but don’t know how. Vulnerability is a really tricky thing, right? Vulnerability means that you’re open to attack. If you’re open to attack, well, that’s the thing as men we’re told that we have to be ready for. We have to protect our women, we have to protect ourselves, we have to protect our communities, protect, protect, protect. Well, if we’re told we have to protect, then we’re not allowed to be vulnerable. It’s that simple.

I think what I’m seeing right now is a lot of men secretly, privately, wanting to change, to be open, to listen, to hear, to learn, to read. Looking for help, because it’s not working for them. Wanting deep friendships, yet not knowing how to have them. Wanting better relationships with the women in their lives, wanting to treat people better, but not knowing how to do it.

The younger generation is coming up and they’re saying, “I don’t want to be like that.” They’re looking at masculinity in a totally different way, which is very exciting. I think every generation is going to come and get better and better and better, but like anything, something has to explode and blow up and be broken for it to be fixed.

You’re seeing a lot of men recognize that they’re not happy. They’re not happy, because even in success, even if they achieve the material success that they thought they wanted, happiness isn’t waiting for them on the other side. It’s not under the rainbow the way they thought it was, and we have to figure out why that is.

Until we recognize that vulnerability exists within us and that accepting who we are, as we are, is enough, then nothing will ever change. We’ll just keep looking and searching for that pot of gold, only to find that it’s not there.

‘Man Enough’ is available from April 27th, published by HarperOne

Who are the female heroes in your life and what have they taught you?

Well, my wife Emily is my hero, that’s for sure. She’s held a mirror up to me since we met, and has taught me so much about myself, as I’ve done for her, but she has reminded me of my worth and my enoughness, yet also challenged me to remove the armor that I put on throughout my entire life. The armor that I put on to go out into the world into battle, and that I put on to protect myself, to make myself feel better, to help me fit in, to make myself feel wanted and liked, to make myself feel enough. She’s helped me take that armor off so that I can actually have a connection, not just with myself but with other people and with her. That’s not always a fun, easy process. That’s one of the beautiful things about marriage. She’s always the one reflecting it back to me.

Another one of my heroes is one of my best friends, Noelle. We grew up together, and she is somebody who’s always, with love, constantly desired for me to be better by asking me to look at certain things, or the way I say things or the way I treat somebody or the way that I respond in an interview or something. She questions me. She’s not afraid to say, “Hey, I know you didn’t mean this, but you said this.”

My mom obviously is always going to be one of my heroes. Despite the complex relationships we have with our parents, she was the person who introduced me to God. She was the one that taught me faith and lived by it, and I’m so grateful.

My Nana Grace, who passed about 18 years ago, I think she was my first friend, and she’ll always be one of my heroes. She was the nurturer in my life, and she taught me that’s also okay, that she was happy doing that. She taught me those beautiful, innate, feminine qualities of that nurturing, and that I could also be that, because I didn’t have a grandpa on that side. I learned how to cook from her. I learned a lot of these things from my nana that I take into my world as a man, which I think is really great.

Justin Baldoni // 📸: Kurt Iswarienko

Do you have a preference between acting, writing, directing, or sharing your philosophy about managing a healthy and happy life? And how do you balance all of these?

I don’t balance them well! Nobody does. The more you do, the bigger your team has to become, the more people it takes to help you remember to drink water. There’s no such thing as balance. It’s about making priorities day by day, in the moment. What am I making a priority for today? How am I going to get through this? How am I going to do all of this?

I don’t really have a preference. I think my preference changes. I think I get bored doing the same thing over and over and over again, that monotony. They say if you love what you do, you don’t have to work a day in your life, but I don’t believe that at all. I love what I do, but I still will find myself wanting a change every once in a while. So long as I’m able to share my experience in a way that is helpful to another person, as long as I’m able to do that and be of service, then I don’t really care what I do.

I always joke that if this all went away, I could open a restaurant and cook and be happy doing that for five years, and then I might find something else I want to do. I think that there’s just too much to do in life. Life’s short. We have only so much time here and we’ve got to make the most of it. At the moment, I’m getting a chance to talk about things that can hopefully be helpful to other people. It’s certainly helpful to myself while I’m talking about them, and that might change in a few years.

Justin Baldoni at the premiere of his film ‘Five Feet Apart’ with stars Cole Sprouse and Haley Lu Richardson

Do you find as an actor you’re more likely to be cast as a specific strong and handsome masculine stereotype, given how you look physically, over being offered more vulnerable roles?

Oh, yeah. I joked about that in my TED Talk, that I was always cast as a certain kind of man, yet never felt like I was that man. What we’ve found as I’ve gotten older is that chances are I’m not going to get that role, because now people know me more as a person than as an actor. It’s almost less believable to see me in those types of roles, although now I actually want to play some of those types because it allows me to tap into a different part of me.

I’m very interested in playing darker characters and things like that. But generally, as I was starting out, even in the character [Rafael] I played on ‘Jane the Virgin’, he was very different than me. But he ended up becoming very similar to me after five years. Obviously you always start from who you are on the outside in the casting world. It’s our job as actors to take our inward, our internal lives, and bring them to the characters.

Justin Baldoni // 📸: Kurt Iswarienko

Do you ever mess up? Because you’re human and I’m sure you do, everyone does. And when that happens, how do you go about making reparations, forgiving yourself and moving on?

That’s a great question. The entire book is me messing up. I think that if I had a superpower — or two — it would be asking for help and admitting when I’m wrong. Those are the two things that I know most men struggle with. When I mess up, one of the things that I like to do is immediately apologize, as soon as I recognize I’m wrong or as soon as I can get past my ego. Then once I do that, I really make an effort to not repeat the mistake, even though I always do. Then I just have to believe or hope that the more I acknowledge those mistakes, the more the people around me trust that It’s something that I’m working on.

Justin Baldoni // 📸: Kurt Iswarienko

You vibrate at a different level because you’re pushing through these boundaries, but it feels like growth and progress. Are there any particular books or favorite authors that have helped to guide you in your journey?

Yeah, there’s a lot, I mean, there’s so many. I’m reading ‘bell hooks’ right now. And I read a book in therapy that was so simple. It’s called ‘The Knight in Rusty Armor.’ It’s around 45 pages, and that book changed my life. My therapist gave it to us as an exercise, and it’s so simple yet so profound. That’s how I framed my book. The knight who didn’t know. The knight who was known for his armor, and yet didn’t know how to take it off.

Justin Baldoni // 📸: Kurt Iswarienko

What’s the single most important change men of all ages can commit to in order to make for a better future? It’s a big question, I know…

There’s not just one thing, but if there was, it has to tie into awareness. I would say to become aware of the invisible forces at play that influence behavior. What is my resistance to helping more with the kids? What is my resistance to cleaning up the kitchen? What is my resistance to doing or folding the laundry? What is my resistance? Why did I interrupt my wife? It’s like being willing to look at the reason and ask yourself why. I think we have to start there.

You can’t just say, “Do the work.” You can’t just say, “Do the laundry.” I think you have to ask yourself the reason why there’s resistance so that you can become aware. Then once you become aware, you change your behavior. You do it, right? That’s how it stays planted in the brain. That’s how we pave new neural pathways.

Asking why. I think that’s the simple version, asking why to ourselves.

Justin Baldoni with fellow cast members of ‘Jane The Virgin’

During the process of writing your book, were you disciplined? What was your routine?

It was hell. It was during the pandemic. It was while I was finishing editing my last film. It was all over the place because every day was different, because our kids were at home and we were all locked in together. I met with tons of resistance as I was working on this book. I would start at 6pm at night and go till two in the morning. It was all kinds of things. It was crazy.

It took a year. A year, but in that year, I also produced and directed a movie. I started my company, I started the studio. It was all of these things together. But I would say that the major lifting was done between February and October.

How do you maintain your positive and generous attitude?

Being surrounded by people who want what’s best for me versus ‘yes’ people. Being surrounded by people that will tell me when I’m wrong and will challenge me. And faith, believing in something greater than myself. Having a north star and having my feet hopefully firmly planted on the ground. Also, it’s not always positive. We all have doubts. You wake up feeling shitty. But you want to make every day better than the day before, and then you keep going.

Justin Baldoni // 📸: Kurt Iswarienko

Grooming by Brent Lavett using Lavett and Chin

From top, Justin wears roll neck sweater by Buck Mason; black t shirt by All Saints, hat by Satya Twena; white pants by SMR Days; check shirt by Faherty. Justin’s own jeans, watch, jewelry and flip flops.