The best — and sometimes the worst — thing about being a journalist is getting a front row seat to history being made.

As an entertainment reporter in London during Amy Winehouse’s reign as the queen of Camden, I saw her perform live many times, from small impromptu pub gigs to iconic large shows. I met her and many of the main players in her story, and was excited to be in the orbit of this once-in-a-generation star.

But with privilege comes responsibility which, in retrospect, was taken too lightly by many who played their part in this tragedy. I was part of the media machine that participated in her rise and fall, turning the twists and turns of her tumultuous life into a real-life rock and roll soap opera. And I have felt uncomfortable about that ever since — feelings which returned to the surface when I watched Back to Black, the new biopic which was released in the US this weekend.

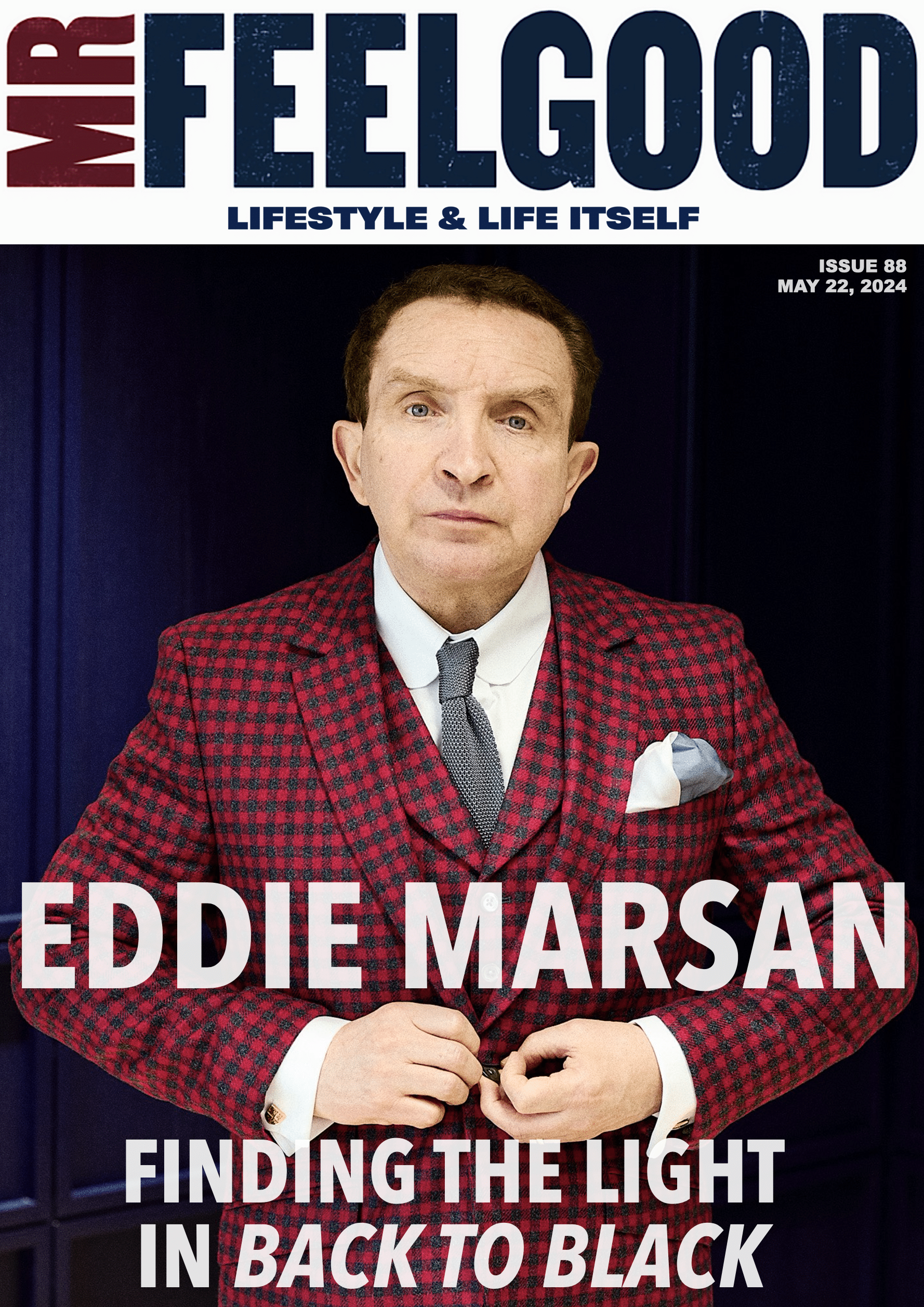

Newspaper journalists — as I was in Amy’s noughties heyday — face justifiable criticism over their pursuit of celebrities; especially troubled ones like Amy, who died of alcohol poisoning in July 2011, aged 27, following a long battle with alcohol and drug addiction. But while the press are certainly on the frontline, the scrutiny shouldn’t end there. Anyone who shares another person’s story has responsibility to their subject, and it’s while carrying that weight that Eddie Marsan agreed to take on the part of Amy’s father Mitch in Back to Black, directed by Sam Taylor-Johnson, and starring Marisa Abela in the lead role.

The movie has been criticized for its tone, which hits more celebratory notes than the Oscar-winning 2015 documentary Amy, which cast Mitch and the singer’s husband Blake Fielder-Civil as the villains of the piece, blaming them for her fatal descent. But for Eddie, playing the role of Mitch had to be approached with empathy. And overall, the movie is careful not to blame anyone for her death (even newspaper journalists!) instead painting Amy as a strong-willed artist whose lust for life — and love — took a dangerous turn into a terminal addiction.

Growing up in Stepney, East London — the same working class area of the English capital as Mitch — Eddie left school at 15 with little in the way of academic qualifications. But through hard work, talent and decency he has grown to become one of the most respected British actors of his generation, working with the best directors in the business including Martin Scorsese in Gangs of New York (2002), Mike Leigh in Vera Drake (2004), and Steven Spielberg in War Horse (2011). He’s perhaps best known for his powerful performance as Terry, a boxing gym owner living with Parkinson’s disease, in Showtime’s hit series Ray Donovan. And he recently hit our screens playing the second US President John Adams in Franklin on Apple TV+, the story of Benjamin Franklin with Michael Douglas in the title role, also starring Daniel Mays, who we profiled in Mr Feelgood earlier this year.

Eddie brings all that experience, and his natural compassion, to the role of Mitch in Back to Black — just as he does to our conversation below. He discusses how respect for Mitch and his plight shaped his approach to the film, and how the critically-acclaimed 2015 documentary that preceded it “almost destroyed” Amy’s grieving dad. And he believes this version — with no clear villains and victims — is a more accurate portrayal of Amy’s life and the challenges facing the families of addicts.

What do you think the movie says about Amy’s addiction, and addiction more broadly?

I don’t think it shied away from it. I think the film is a brilliant celebration of her, and told from her perspective. So you could see why she fell in love with Blake, and how much she loved her dad.

The documentary that came out [Amy, in 2015] had a certain narrative that blamed Mitch and Blake. But once we started to make the drama, we knew we had to engage empathy. And once you engage empathy, to understand the characters within the story, you realize that you couldn’t make a film version of the documentary. Because people aren’t all villains or victims, people are complex.

I think one of the hardest things for the film was that people were so attached to the narrative of the documentary, and this film challenges that narrative. So they think that we sugarcoated things, but we didn’t. Amy loved her dad and she loved her husband. The family tried nine interventions, tried to get her into rehab nine times. She came from a very loving family, but she was an addict. And so I’m very proud of the film, that it shows that she was loved.

It’s a very uncomfortable narrative, because there’s no villain and there’s no victim. But that’s more true to addiction, I feel.

I thought there was something unspectacular about her alcohol and drug abuse in the film, which I thought was quite realistic. Her addictions just sort of crept up on her.

When you make dramas like this, you can forget that they were kids. But it doesn’t infantilize Amy, they were also in control of their own lives. It doesn’t make her the victim of other people’s manipulation. And I think that’s a more accurate portrayal of the situation as it was. In speaking to people who worked with Amy, you couldn’t tell her what to do. She wasn’t forced to go on stage, she wasn’t forced to do anything.

You’re a dad of four kids. I thought the movie raised interesting points about Mitch’s helplessness, and how much any parent can intervene in a situation like this. The script emphasizes that line in Rehab, ‘My daddy thinks I’m fine.’ And that was true to an extent, perhaps Mitch didn’t push her too hard towards rehab in the early days of her addiction, but experts do say you have to wait for the addict to be ready.

Mitch was just a cab driver. His daughter was a pop star, and she was an addict. He just thought that if you kept her busy, and kept her focused on the music, that would keep her alive. He felt that if they would have put her in rehab at that time, she could have lost her contract with Island and gone down a black hole. So he told the manager to keep her working, not because he was making any money out of it, but because he thought that was the best way to keep her healthy. Then later they realized they had to put her into rehab. But that’s just a man figuring it out. So many parents who are dealing with kids who have addiction try so many things before they put them in rehab.

We live in a world now, especially with social media, where there’s villains and victims and no nuance. No-one’s portrayed as a human being anymore. And as a father-of-four myself, I don’t know if I would have been any more successful in Mitch’s situation. I honestly don’t.

What contact did you have with Mitch, and how did you find him as a man?

Sam [Taylor-Johnson, the director] introduced me to him. When I first went in, he said, “Here’s another Stepney boy!” because we both grew up in Stepney, East London. We spoke for ages, had lunch and dinner a few times. We both love jazz, so we talked about that. I would get him to give me family photographs, ask him to give me an outline of where he went to school, where he was brought up. I asked him to give me a playlist of his favorite songs. And then I asked him to record Fly Me to the Moon for me because I had to sing it in a film. So he was my main source of reference, and he was brilliant. The poor man didn’t know what hit him because I asked him so many questions. But that’s the way I work, I’m not a very academic person and more visceral in the way I take in information.

How is he doing, 13 years on from losing his daughter?

Well, they do a lot of really good work with the foundation. I think the Amy Winehouse Foundation is a means by which they can deal with the grief and find some kind of purpose to their lives. I think that helps the whole family, because they’re creating a more positive narrative.

I think the documentary broke him. It almost destroyed him. He told me a story that he was on a plane, walked to the toilet, and everyone on the plane was watching the Amy documentary, and he realized that everybody on that plane hated him. This is a man who is still recovering from the death of his daughter.

Amy was an icon and the whole nation felt they had a claim to her. But when you get to know the family, you realize that she’s someone’s daughter who died at the age of 27. So for me, and for those of us who had more direct dealings with the family, the empathy kicks in. I think they’ve been really hard done by. I think that she came from a loving family and they were in an impossible situation. Rehab centers are full of people who have died from addiction, but come from loving families. The idea that you have to find a villain behind this might sell tickets and win awards, but I think it’s a load of bollocks.

How did your own experiences as a father affect how you approached the role?

When they approached me to do the film, I knew there was a prevailing narrative because of the documentary, and I wasn’t sure I wanted to do a film that mirrored that. I spoke to a friend of mine who knew Mitch well, and he said he was a good man. I wanted to portray a man who loved his daughter but made mistakes, because that’s what I am. I’ve got four kids I love with all my heart, and I make mistakes every day. I’ve got no time for this righteous indignation that people have, where they judge people. I don’t think it’s reflective of life in general.

In taking on the role of Amy, Marisa Abela has had a bit of a taste of what intense media scrutiny can feel like, and it’s not all been positive.

When we were making the film, there were real paparazzi taking photographs, and within 40 minutes there would be pictures online and comments about how terrible the film is, and who is this girl playing Amy… People feel such an ownership over Amy. I knew some really intelligent journalists, whose writing I like, who were writing negative things about the film without even seeing it. They just hated the idea of it. Marisa had to keep getting up every day, and giving her best. I felt very protective of her.

I’d love to hear a bit more about your path to becoming such a successful actor; how you went from a working class East London upbringing to Hollywood and movie premieres and all that kind of thing, and what wisdom you have learned along the way.

I left school at 15 and started working for an East End bookmaker who also ran a menswear store. I used to work there on a Saturday selling clothes while I was doing an apprenticeship as a printer. I also used to dance a lot, and I was in a club in Hackney and some bloke asked me and my mate to be extras in the film. I saw Jamie Foreman do a scene and he was brilliant, and it inspired me to want to become an actor. It took me years to get into drama school. I tried them all but had no academic point of reference, and didn’t pass the audition for any of them. I eventually got into Mountview and the man I worked for, Leslie Bennett, paid for me to go to drama school for the first year, and I won a scholarship for the second year.

Then I came out of drama school and because I was an East End boy from a council estate, every part I was offered was a drug dealer, mugger, skinhead, or racist. And I realized very early on, I didn’t want to be a professional caricature, I wanted to be an actor. So I went back and started studying in the evenings with voice and movement coaches. Because this industry is run by people who have a more privileged background, I didn’t want them to define who I was. I wanted to be as diverse as I could. My main inspiration was Gary Oldman, I just wanted to be as diverse as him. And I had to go to America to do Ray Donovan to really achieve that diversity.

So what I would say to young kids from underprivileged backgrounds is don’t let anybody tell you that your artistic creation is limited by your race or your religion or your class or your sexuality. Nothing human is alien to me. You can play and do anything. People from more privileged backgrounds have control of this industry. If they define you, they control you. Don’t let them define you.

You mentioned Ray Donovan there. That role really is one of the greatest TV characters of our era. And you’ve worked with many of the greatest actors and directors along the way. What have you learned from them?

Ray Donovan was one of the best jobs. The writers would come down and watch you perform, and write for you, and it was kind of a more holistic approach to creating a character because you did it over many years. I loved playing Terry because he was very masculine, very alpha male, but his job in the show was to be the mother of the family. So he had a very feminine energy and there was a dichotomy within him.

I’ve just done Franklin for Apple with Tim Van Patten, he’s a brilliant director, he directed Game of Thrones and Boardwalk Empire. Martin Scorsese was brilliant and lovely. When he didn’t know what to do, he would admit he didn’t know the answers, and that takes you to a place where you have to be brave and creative to find them. Steven Spielberg was great too. He had the enthusiasm of a drama student. All the best directors have very little ego.

One of the main people I learned from was Jim Broadbent. I spent nine months with him on Gangs of New York and learned so much about acting, just being beside him. I’ve done a few jobs but Tim Spall who has just won a BAFTA, he was one of my heroes. I’ve been lucky enough to work with many brilliant actors, and I’ve nicked something off all of them, to be honest!

Photo assistance by Steve Hardman

With thanks to Joe Fuller

Shot on location at

46 Marshall Street,

London W1