If the music business was to anoint its own in-house oracle, Zane Lowe would be the chosen one. He’s been the industry’s guiding light for two decades; first in Britain as BBC Radio 1’s lord of new music, and now as the thought leader of Apple Music 1, on which he hosts a daily show from Los Angeles, as well as being the platform’s creative director.

Alongside his well-earned reputation as one of the world’s sagest music tastemakers, he’s also become known as an elevated communicator, who the biggest stars on the planet visit to have their most searching and honest conversations. Justin Bieber is among those to have shed tears in one of the self-reflective confessionals that have become Zane’s forte. While other A-listers, including Harry Styles earlier this year, are swerving the bluster of traditional publicity tours and making a deep and meaningful with the DJ the centerpiece of their album promotion.

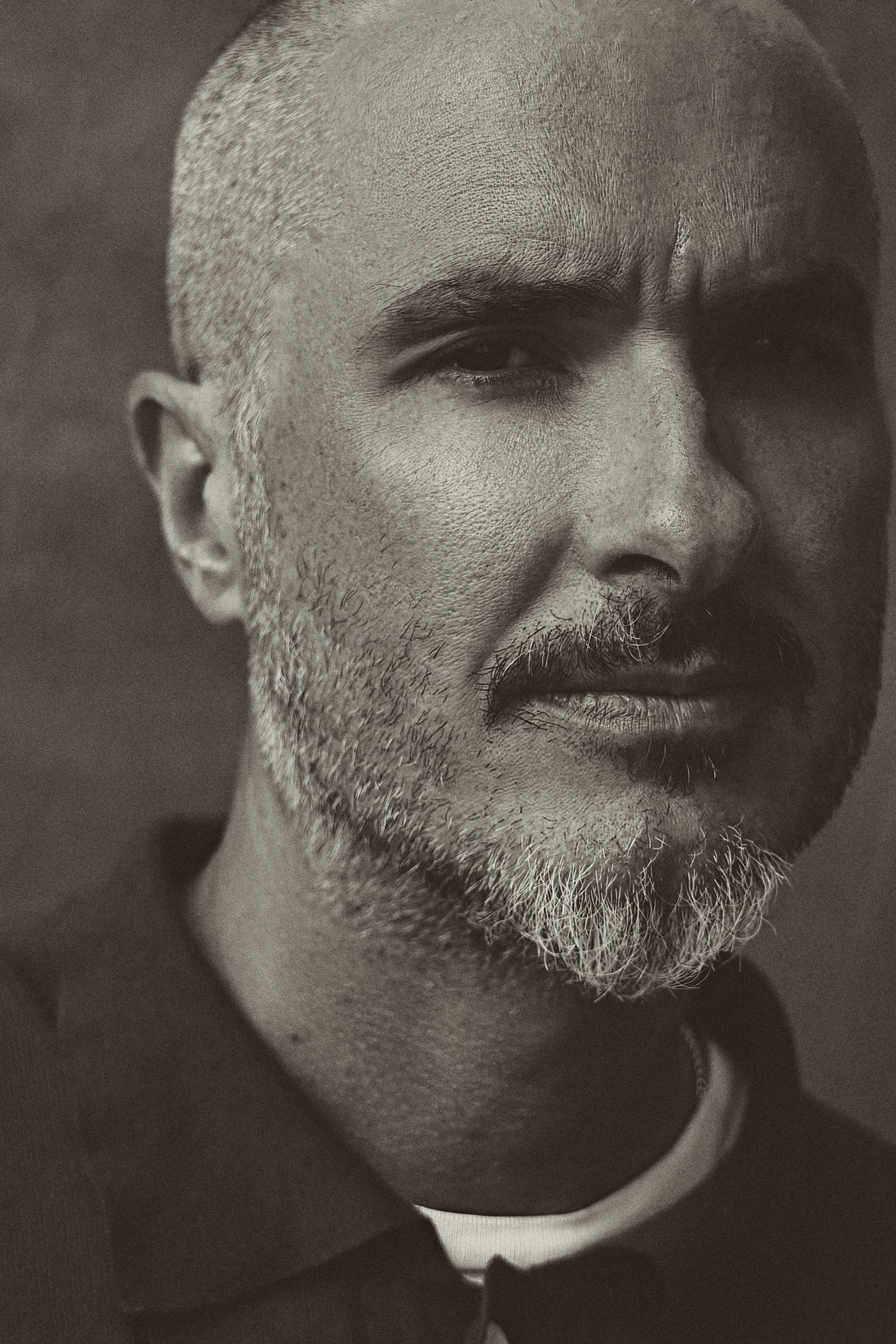

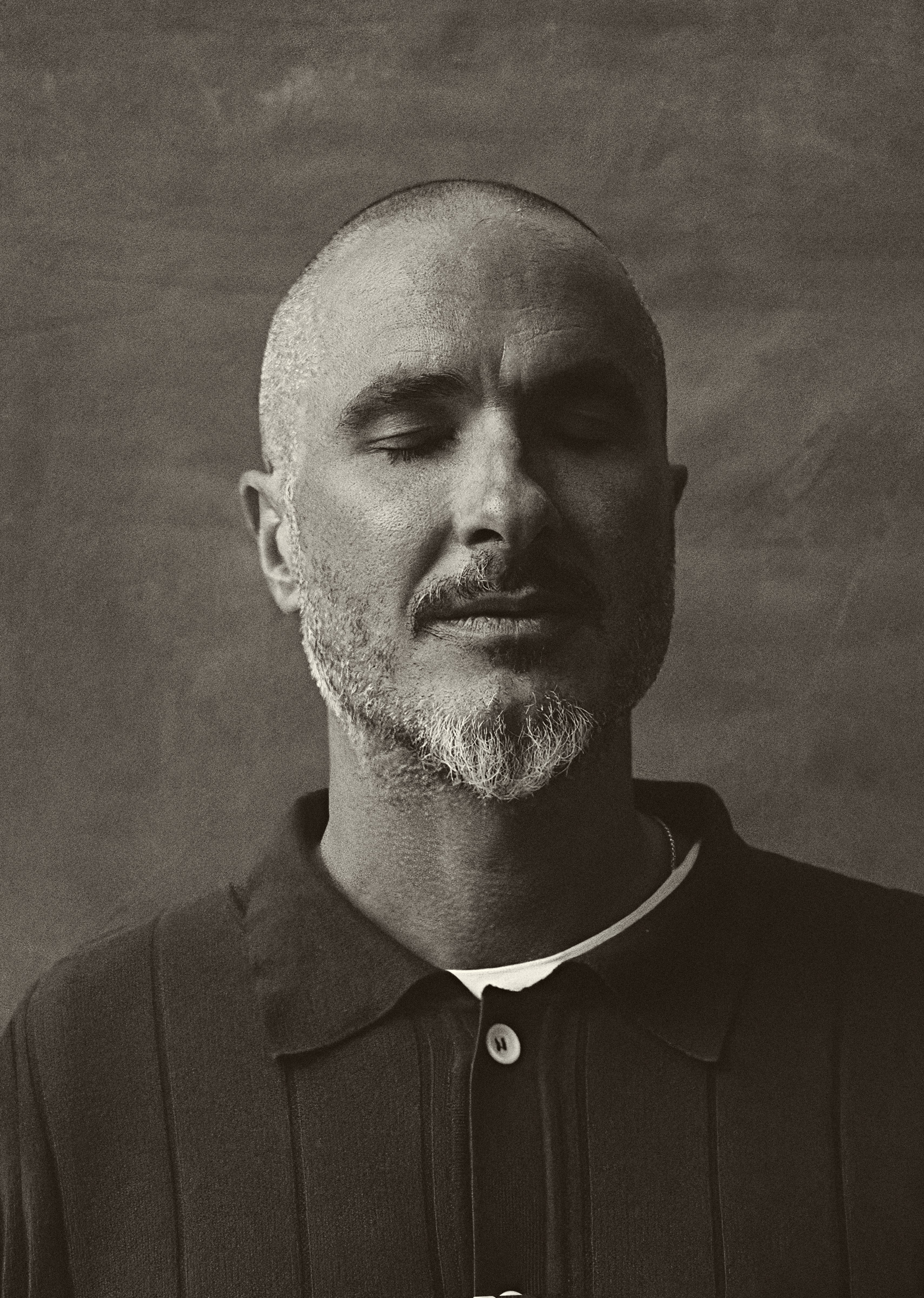

The New Zealander even effortlessly pulls off that floaty ‘spiritual-chic’ look; slender, stubbly, and shaven-headed, normally dressed comfortably cool in lightweight cotton, giving off the vibe of a man who is probably barefoot under the mixing desk. Or sockless at least.

So as Zane enters his clean, white office at Apple Music HQ in Culver City, California, I’m a little more nervous than before the typical profile chat. Firstly, I know I’m interviewing a master of the craft of conversation, and secondly, a man who exudes this mysterious thing called mindfulness, something we are devoted to exploring at Mr Feelgood, despite having so much to learn ourselves.

But like the professional talker he is, Zane quickly puts me at ease, helped by the early revelation that he does not meditate. “I love the idea of it,” he says. “I’d say almost every day, if not every day, I have a fleeting thought about meditation…” We share a joke about how long that thought would have to be before it becomes a meditation. Zane then laughs at my graceless gag about whether a meditative state is achieved by simply sitting on the toilet without your phone. And breathe. I can relax, reminded this is a mere mortal who lived in London longer than he has California. But of course, as our conversation develops, it becomes clear that when it comes to leading the life that meditation teaches, Zane is already in deep. And he dove in many years before most, with his open-minded, receptive approach to his work and life — built around being in the present and listening, really listening, to music, people, and the world around him.

“What I’m doing in the absence of that [meditation] discipline, is trying to do it a little bit, all the time,” he explains. “So I make sure I get outside, and make sure that I actually acknowledged that I’m outside. It’s easy to move from A to B and not really acknowledge anything. But it’s really simple — just stop for a second and listen, look around, and try to be present. Because if you’re present, you’ll see some things that you’re happy about, and maybe that little bit of gratitude might turn the tables a bit, and start to bring some of that good energy back into your life on a day when you need some. When you just open yourself up to that within the intricate framework of your day – rather than carving out an hour for meditation, which I wholeheartedly cannot wait to do in the future — but when you allow it to just be available to you, it’s amazing what it will unlock in you.”

This kind of meditative approach to life, and conversation, is a large part of the reason that the cream of the music industry are queuing up to spend an hour or more in Zane’s company. And he brings out the same thoughtful qualities in his guests, as he grants them the space and respect to discuss their artistry on their terms. Zane has approached his work like this for many years, and now the rest of the media world — where fluid, long-form podcasts have started to find a huge mainstream audience — has caught up.

“Things have changed because the media is now democratized in terms of duration and format,” he says. “So a great conversation is a great conversation, it doesn’t have to fit between two goalposts anymore. But even early on, I was unapologetic about not wanting to rush the process. In doing so I knew I was on a much slower journey than my peers, because the way I wanted to do it, I was never going to have a ‘hit’ to fast track me into the mainstream.

“A good friend of mine gave me a great piece of advice early on; that there’s a room, and everyone’s in the middle of it trying to be seen. But there’s also four corners. And just because you’re in the corner doesn’t mean you’re not in the room. People will get sick of being in that thrash in the center, and they’ll come to your corner and see what that’s about. And then you’ve got opportunity to make a connection and create something meaningful.”

Zane moved to the UK from his native Auckland, New Zealand, in 1997, which was in the height of Britpop — when the biggest two bands in the country were Oasis and the Spice Girls, full of characters who loved thrashing it out in the center of rooms. But over the course of a 25-year career at the peak of music broadcasting — which saw him join BBC Radio 1 in 2003, and then Apple Music in 2015 — more and more of the entertainment A-list have joined him in his corner, having more nuanced conversations than the structure of mainstream media previously encouraged. Harry Styles is now pop’s kingpin. While Oasis sang about ‘Cigarettes & Alcohol’, Harry urges fans to ‘Treat People With Kindness’. And when the singer released his latest album, ‘Harry’s House’, in May, his flagship interview was an 88-minute conversation with Zane, the sun setting behind their blissful corner of Palm Springs, discussing life balance, therapy, and mental health.

“So now you’ve got nearly nine million people who have watched my Harry interview. And you can definitely argue that’s predominantly because of Harry! But he wanted to have that conversation, and that’s a byproduct of 30 years of building up to that. What I’ve realized over the course of my life is that it’s nice to look at the numbers and see that they continue to grow, and it’s nice to have something that flies off the shelf. But it’s not the thing that you reflect on, you reflect on the experience. So I won’t reflect on the number, I’ll reflect on the two hours I spent with Harry. To try to get ahead of that experience is to ignore the joy that is right in front of you.”

The kind of emotionally-honest discussions that Zane inspires seem to come quite naturally to the new pop music elite. I co-founded Mr Feelgood, with my friend John Pearson, to encourage more meaningful conversations between men, and because I had reached a stage in my life, entering my 40s, when I wanted to create opportunities to have more of these conversations myself. But for many younger people this internal examination, and subsequent sharing, is their first language. And while the platform offered by advancing technology and evolving media strikes fear into many of Zane’s generation, it’s a shift that makes the 49-year-old hopeful for the future.

“If you look at the way we absorbed information when we were younger, a lot of decisions were made for us,” he says. “And then in the last 10 or 20 years, as information has become more readily available, there’s a lot more questioning. So younger people growing up in that world have an ability to see multiple outcomes. They can absorb information in multiple ways, and decide which one speaks to them, and learn accordingly, which I find really fascinating.

“The people make the change. It’s not the people who deliver the information, it’s the people who absorb it. And I’m actually pretty optimistic. Emotional intelligence is now forming a really important part of how people process information and situations. I genuinely feel that, within all the negativity and the misinformation, there’s also this new muscle that is developing where certain things are being questioned that weren’t before.”

Alongside the constant education he receives from his two teenage sons, Zane meets wonderful young teachers on a daily basis at work. One of his recent lessons came from Jacob Collier, the 28-year-old jazz multi-instrumentalist who is the first British artist to receive a Grammy Award for each of his first four albums. “We were talking about the 12 established notes in music, and Jacob said, ‘But there are infinite notes between the notes. We haven’t called them anything yet, but they all make you feel something.’ There’s so much we don’t know.”

Zane goes a little deeper. “We do such a good job of trying to control everything, from childbirth that’s what it’s about. Our incredible mothers let go, and that’s the first experience we have, and then after that everything is about holding on. ‘Hold my hand,’ ‘Be careful,’ ‘Don’t spill it.’ And really, what we need to do is to develop tools to let go as much as possible, to try and create space to learn new things. I think that by communicating, and having conversations that are more open, in many respect we’re lowering the amount of space taken up with unnecessary things. So I think it’s almost part survival, part instinct for kids now.”

In a more analog era, Zane turned to music when he was following his own survival instincts as a kid, looking for both connection and escape as his parents went through a difficult divorce.

“Music played a really important role in helping me process stuff that was going on, that I was too young to understand,” he says. “The breakdown of my family, the separation of my parents, and not really knowing how to contribute or be of service there. And also not really knowing how to have those conversations — or who to talk to — back in the ’80s. I thought at the time we were the only family in Auckland who were going through a divorce, which is crazy to acknowledge as it’s totally not true. But as I went through school, I felt like people were talking to me differently, and treating me differently. So I was searching for escape, and I was drawn to music.

“For me, music was the starting point of forging an identity. It’s where I got a lot of my insight into the human condition, before I even really knew what some of the words meant. And I was searching for that because I was on the frontline in my own home, seeing real pain in real time. I was just searching for a companion.”

Among the most influential records in Zane’s youth was Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers’ ‘Damn the Torpedoes’, produced by Jimmy Iovine, who would go be central to the creation of Apple Music after the technology giant acquired his company Beats Electronics, and was involved in hiring Zane to spearhead the station, originally called Beats 1. But it was in rap music that Zane really found the sense of belonging he was searching for, even though it detached him further from most of his local peers.

“I was obsessed with the art form, and watched as it became the most successful form of modern music on the planet,” he says. “I knew it was born out of struggle, but I didn’t understand the nuance of it. And that’s why it’s been a huge journey for the whole world, and such an incredible, powerful art form, because not only has it told us individual stories, it’s also told a much bigger story.

“I used to get a hard time for liking that sort of music. And I remember I was going through quite a significant period of my life where I was quite badly bullied at school. My mom came to my rescue at the time, and she said to a neighbor who was an old friend of my brothers, ‘He’s got no mates right now and he’s pretty lonely. I noticed you have some rap albums in the house. Would you hang out with him once in a while?’ We felt like we were a part of a very small group of people in Aukland who were into this music.”

Zane’s childhood dream was to become a music maker himself (and he went on to earn a producing and writing credit on Sam Smith’s Grammy-winning 2014 album ‘In the Lonely Hour’). But concerned that he was drifting towards some of the less healthy trappings of life as a bedroom artist, his parents found common ground to connect him with a job working nights as a runner at Max TV, New Zealand’s answer to MTV which ran for four years in the mid-1990s, giving him his first step into broadcasting.

“I was in my late teens, early 20s, and I was sort of dropping out,” he recalls. “All I wanted to do was sit in my bedroom and make beats, and produce rap records, and see where that took me. But I did that while drinking a six-pack of beer and eating McDonald’s every day. So that’s not a good day for a parent, when your kids half drunk by 3pm and is sitting in his room, thinking he’s doing something with his life because he’s just sampled an Eric Dolphy record.”

After moving to the UK aged 24, he rose to prominence on MTV and the indie radio station XFM before landing his primetime spot on BBC Radio 1. He became best known as a champion of new music, with his signature being his ‘Hottest Record in The World’ feature, which brought career-changing attention to an eclectic array of artists and bands. In one of the DJ’s most recent Apple Music 1 interviews, The 1975 frontman Matt Healy described how Zane playing the band’s debut single ‘The City’ on his show in 2012 kickstarted their career. Ed Sheeran told him the same about his first single ‘The A Team’. These are just two of countless examples of world famous artists who Zane helped along the way, and have returned the favor by coming back for interviews at various significant turning points throughout their lives. For me, as an entertainment journalist working in London in the noughties, Zane’s show was essential listening to keep an ear out for new acts breaking through. At the time, music was more tribal than it is today, with most young people identifying with a particular genre — whether that be rap, rock, or dance. Zane’s show played the best of all tastes, and he has continued to show equal respect to the artistry of all performers, from mainstream pop to obscure punk, in his long-form interviews.

“I think I always had a curiosity for conversation,” he says. “And as long as I can remember, my mom would say that her adult friends would enjoy talking with me as a kid. They’d say I was an ‘old soul’, which was a compliment at the time. I think that means you’re searching for some recognition by being of value to a conversation you really don’t have the tools to be a part of. So that’s where the seeds of conversation began for me. When I felt quite alone as a kid, I saw it as a way of being seen. And then as time went on I added my passion for music, and I took that skill for conversation, and I mixed it with this deep curiosity, and desire to get closer to process, which only happens through speaking to the artist.”

As we get deeper under the skin of Zane’s approach to his work, he talks further about his desire to get inside both the “purpose” and “process” of musicians. “The purpose is what motivates the art, and the process is how you make it,” he explains. And I recognize that as what I am also trying to achieve in this conversation, as I attempt to understand and learn from Zane’s personal art form of the music interview. And if there’s one piece of guidance that will stay with me long after this conversation, it’s this one: “The big shift for me was I used to prepare to talk, and now I prepare to listen. I no longer prepare to ask questions, but to respond to answers. That’s where it got interesting for me, when I realized that I was just a student in the conversation.”

So, given his opportunities to learn from some of the brightest artistic minds on the planet, in particular discussing the relationship between creativity and mental health, I’m interested to know how that has impacted his own headspace. “I’m an anxious person, there’s no doubt about that. And I’ve been through my fair share of work, and I continue to do the work. It’s not something that you ever ultimately solve. For me, I’m not looking for answers anymore, I’m looking for process, I’m looking for tools. I’m looking for things that can help myself, and then that might help the way I process other people’s situations, in a way that is less about being part of any solution, and more about being part of that experience.”

Zane’s also aware that he has to careful not to confuse being a good interviewer with being a good husband, father, son, or friend. This was particularly true during the pandemic, where he was connecting with artists via video chats from their homes, and the themes of these conversations — dealing with the anxiety and isolation of lockdown — was earning Zane praise as the industry’s accidental therapist.

“I didn’t start to have conversations with artists that entered deeper places, and allowed me to better understand the artistic spirit, and then come home and be like, ‘Wow, I’m so much further down my road.’ In fact, the only conscious decision I had to make a couple of years back was to separate the two.

“I was having these deep conversations virtually, and then I’m living in a house with people whom like the rest of the world, were experiencing their own unique chemistry of anxiety, fear and isolation. And I was faced with this very clear realization, which was these conversations have no bearing on what’s going on in my life. And no bearing on what’s going on with my kids, my wife, my brother, my sister-in-law, my dad, my mom, or my friends.

“I’ve got to attend to that and in a unique and thoughtful way, and not assume that I have any deeper understanding of that just because I had a great hour [talking to an artist]. That doesn’t mean that I don’t learn from these conversations, and take things that I’m going to carry with me; quotes, or ideas, or thoughts, or stories. But I’m never going to build a conscious bridge between the two, because I need the space to be able to build the best experience for me and my family. Every situation is different.”

Gratitude is also central to Zane’s health and happiness, although much like his relationship with other forms of mindfulness, it’s not something that he uses an app to practice — but a constant mindset that he tries to thread through his life. (Although he’s also keen to point out he is in favor of “packaging mindfulness” if it helps to engage more people in beneficial habits. Much like his relationship with music, he can appreciate the modern pop approach alongside the classics.)

“When I go to bed at night, I think, ‘What did I do today?’ Sometimes I fall asleep before I’ve finished the list. And that’s not because I live this full life where I’ve got all these amazing things, although I’m very grateful for my life and what I do on a daily basis. But I go into real detail, and by the time I get to 11am, I am falling asleep. Gratitude f***ing works, because it reminds you what a gift it all is. When we go for a meal, for example, there are people that put their heart and soul into cooking it, so acknowledge that. It’s just allowing ourselves to have the space to appreciate it.”

He swears by yoga too, and says that giving it more focus during the pandemic helped to hone his skills. “I was doing it for the wrong reasons. I started doing it for physical reasons, then I realized that actually it was about breathing, and the mental health of it. And once I figured out that that’s the thing I need to concentrate on, then the physical followed.”

Zane’s zen demeanor is momentarily challenged when I bring up an interview I read with the former British Prime Minister Tony Blair earlier this year, who voiced concerns about young people in the West becoming too obsessed with introspection. Blair was essentially saying it was having a negative impact on our mental health and productivity as we’re losing the stoicism in the face of adversity — the stiff upper lip — that his generation were taught. So could it be we’re now examining and speaking about our feelings too much?

“We as a species are driven to connection,” Zane says, with a touch of bristle. “I think we instinctively want it. So whether it’s oversharing, over scrolling, maybe we’re overdoing everything. We just came out of two-and-a-half years of pandemic, so let’s cut ourselves some slack. The world is not turning in a way that makes us feel secure about the future. So maybe a little more self-reflection is a good thing.”

He saves his more forthright thoughts on a politician, who made some questionable life-and-death decisions, passing judgement on what young people choose to do with their minds for when the tape isn’t rolling. And as we shoot some portraits in and around his Apple Music studio, it falls to our photographer Austin Hargrave to ask the question I probably should have, that many of you are probably here to find out. What new artist should we be looking out for right now? His answer: Wunderhorse. Sounds like a tip worth listening to.

[…] Samson, P 2022, ‘Zane Lowe on the Art of Listening’, Mr Feelgood, https://mrfeelgood.com/articles/zane-lowe-on-the-art-of-listening […]