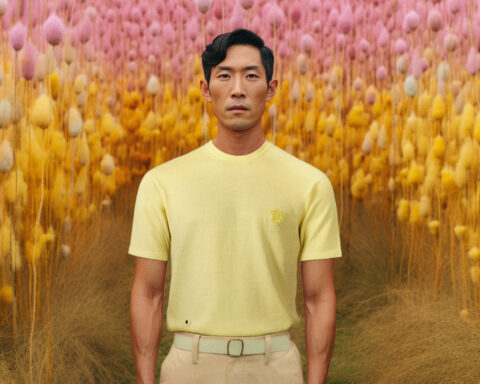

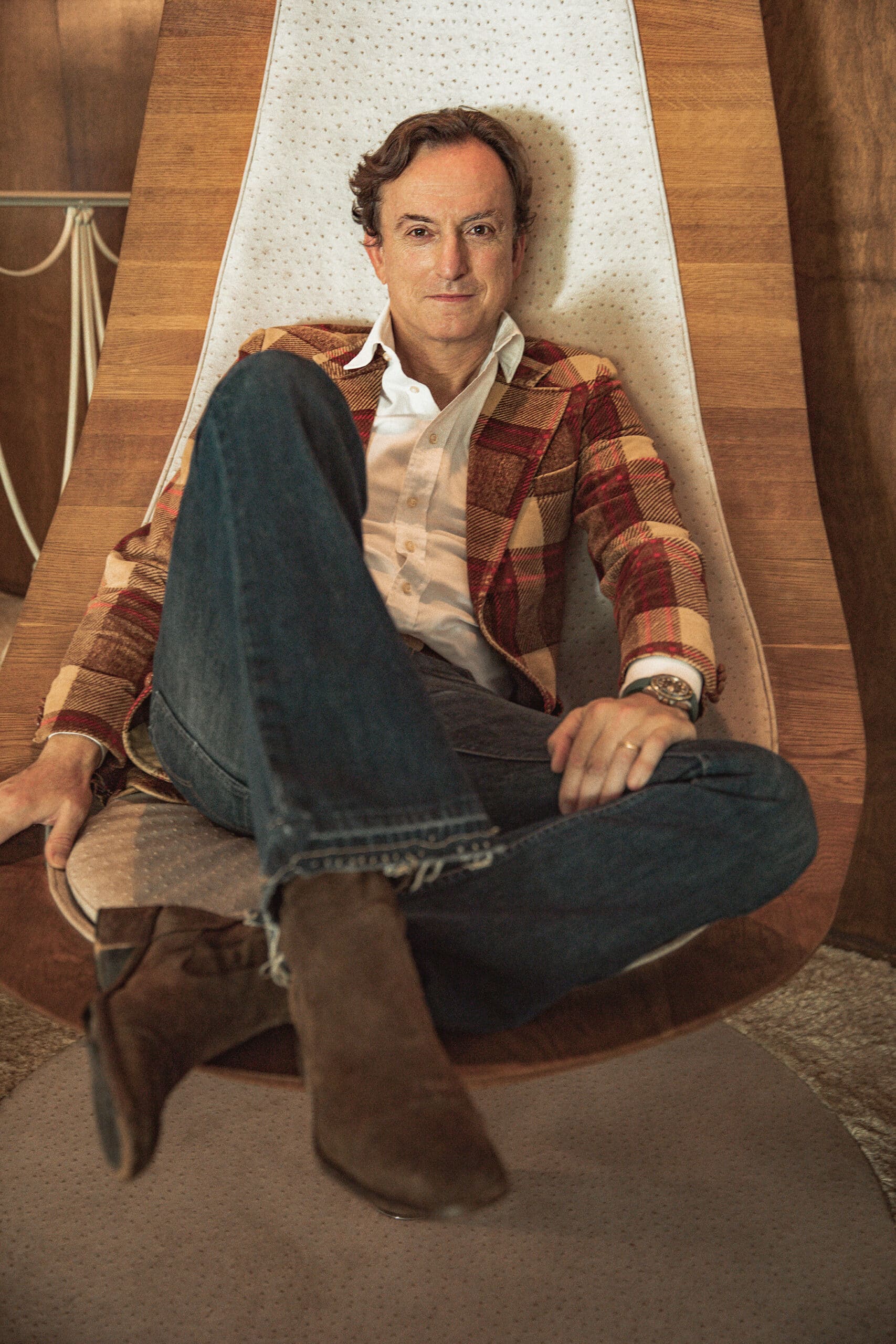

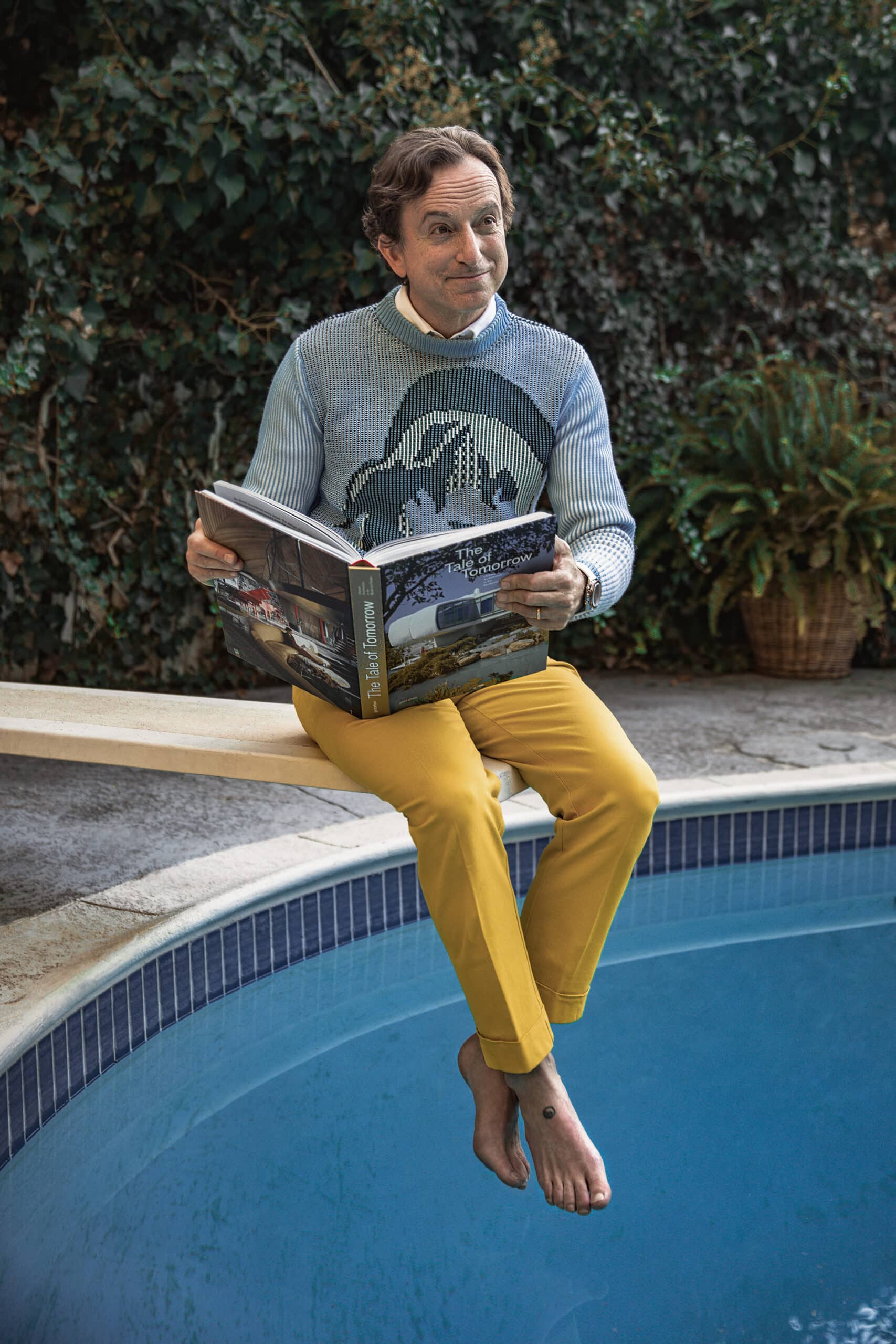

To spend time in the company of architect and designer Nicolò Bini is to be infused with the passion of the man. Born in Italy, formatively schooled in Australia, and attending college and thriving professionally in California, Nicolò is a perfect mix of the best of all those places. His Italian side is rich with feelings, taste and sensitivity. His Aussie side is frank, humorous and home to where his love for surfing was born. And his Californian influence is where his attitude that all things are possible comes from.

Nicolò, 55, is a born dreamer with the astute academic practicality to not only imagine, but also search in and out of the box, for solutions to the conundrums of developing new technologies to build better structures of all shapes and sizes. All this is married with a deep reverence to the philosophy that we must observe and look for answers within the limitless realms of nature. These are the core principles at the heart of Binishells, Nicolò’s groundbreaking architecture firm.

“Study nature, it will never lead you astray,” he says. “Study it, it will only give you answers. Nature’s most important mission is to survive. It’s a self-replicating machine which teaches us many things. Consider the egg. When you study it, it is unbelievable; housing the most volume, for the least amount of material, and a strength that’s distributed monolithically, perfectly. And thus, the least amount of material equals the least amount of weight, transferred over the entire perimeter, meaning the entire thing works to counter the weight in the most elegant way.” Fantastic insight!

Amongst other things, Nicolò is the architect behind Robert Downey Jr’s beautiful 6,500 square foot aerodynamic home, as featured recently in The New York Times. The Downey’s abode, set amongst a seven-acre spread of prime ocean-viewing Malibu, evokes sensual primal curves with a science fiction-like adobe minimalism. Futuristic, perhaps, but also with an unmistakable nod to the exquisite symmetry of nature, all intended with sustainability and low-impact environmental principles in mind.

But let’s return to this talented creator’s foundations. Nicolò’s foremost influence came from his father, Dante Bini, the renowned architect and industrial designer. “Philosophically my father has a very close connection with nature,” he says. “He taught me to look outside the box.” Considered a bona fide genius within his circle, the elder Bini began in his family’s wine business, designing packaging, before deciding to attend architectural school. On being accepted, Dante travelled the long distance from Bologna to Florence every day, taking the train or riding his Vespa, no small task given the one-way journey in those days took at least 90 minutes. In the competitive architectural talent pool, Dante soon realized that to be successful, he’d have to do something different, and his original idea for Binishells came about whilst playing tennis in an inflatable shell during a snowstorm in Italy. Oblivious to what was going on outside, on finishing his match, it took he and his friend quite some time to dig their way out of the fallen snow. And this is when Dante realized that when inside the structure, he couldn’t feel the pressure brought on by the storm.

Inspired by this experience, the seed of Binishells was conceived, whereby he realized that replicating the physics of inflating a balloon, by covering a nylon-coated neoprene air membrane with wet steel-reinforced concrete, then gradually inflating it using low air pressure, he could create, in a very short time, an aerodynamic and sturdy thin-shelled structure, which used far less materials, fitted seamlessly with the natural undulations of the landscape, and was a much more time and waste efficient alternative to the building technologies of the day.

This was 1964 and it proved big news, sensational, and was covered by the world’s most prestigious newspapers. Very soon Dante was in high demand, building shells of all different sizes, covering a vast array of purposes including shopping centers, libraries, schools, and homes, most notably the now derelict ‘La Cupola’, perched atop a cliff in Sardinia, which was a love nest commissioned by the great doyen of modernist Italian cinema, Michelangelo Antonioni and his muse, the actress Monica Vitti.

As of now, over 1,600 Binishells can be found in 23 different countries around the world and Nicolò, in his perpetual drive to develop environmentally-friendly, multipurpose, energy efficient, affordable living complexes, has taken it upon himself to continue where his father (who remains, at 90 years old, active on the lecture circuit) left off, bringing the technologies up to contemporary code, and improving on his dad’s original concept. It is a natural evolution and one that Nicolò has been involved with since his teens, when he used to translate his father’s papers from his native Italian into English. Nicolò also accompanied his Dante on global business trips, absorbing, having to learn and be accountable, and also possessing a very curious mind, debating the full gamut of ‘what if?’

Taking time out to study technology at Berkeley, Nicolò graduated as valedictorian, completing his thesis on low-cost housing, which remains his big passion to this day. “It’s so needed. So difficult, but needed,” he says. After a short spell working in Italy, and then the US, at regular architecture firms, he grew tired of such and began working for the GAP clothing brand. “It was actually really great, learning an entire new side of things that I had no clue about but that really fascinated me.” He worked on store design, retail design, branding. “All the stuff which is hugely important to me today.”

Leaving there, he then formed his own company focussing on retail and residential. He began in retail because that’s where all his contacts were at the time, and ended up doing many stores around the world for prestigious brands. He also created some houses for high-end clients for which he remains proud of, but when his first daughter was born, began to question where he was placing his attention. “I thought I really cared about the other stuff,” he recalls. But in considering being judged by his children on what he contributed to the world, he realized that “you’re either part of the problem or you’re part of the solution.” This led him to consider returning to his predominant passion of seeking solutions to local housing, and of updating and utilizing the technological innovations his father discovered.

Nicolò explains, “It turns out, all the basic methodologies for Binishells are absolutely no longer code compliant, not only here but everywhere in the world. With reinforcement in concrete, the placement of the steel is critical. It always has been but now they’re more precise about it. In the instance of my father, you would lay the steel, you would cover it with concrete then never see it again. Then you would inflate and make your building. If something went wrong, there was no one to blame because everything was encased.” Nowadays of course, with strict regulations, every aspect of the building has to be signed off. Nicolò’s solution to the problem was, “Let’s inflate it first, and then put the steel on — suddenly it works and now it’s also code compliant.”

In examining the traditional ways of building structures, it’s clear that there is much waste. “They would construct a building out of wood, with a vessel to contain the steel and concrete mass, sometimes in extraordinary shapes. That looked like it was natural, but it was in fact hard work; the lattice of the wood, the pouring of the concrete, and then throwing the whole first building away.” Nicolò was intrigued by the notion of less material, less labor, speed and being ever conscious of the overall carbon footprint.

He explains, “Material is important to ensure you have a lower carbon footprint, but the lifecycle footprint is what you’re interested in because buildings are supposed to last 100 to 200 years. So during the course of a 70 year old building, it’s the energy which is the big waste. If you have a building that’s made of hundreds of pieces of things all stuck together, compared to something that’s built monolithically, the traditional build is like a glass that is full of holes. You need to keep putting the liquid in. But when it’s a vessel, the heat stays in and it’s on another level environmentally. We’re talking conservatively about using 20% to 25% of the energy and using half of the materials and greener materials. And then you think about it from a safety perspective. We spend 90% of our time indoors, we spend our money on our homes. So money and time are our biggest resources by far. And all these resources go into buildings which are incredibly unsafe. They are not safe as investments, to house our loved ones and all your most important possessions. All our time is spent here and yet we haven’t evolved in the industry of construction since they came up with the steel frame around 1850. A home is a work of art and needs to be respected as such.”

Furthermore on the subject of safety, Binishells are safer in earthquakes as the forces are distributed evenly, in high winds, due to the aerodynamic nature of the design, and in fires because of the non-combustible nature of the building’s envelope. Perfect for California, but also standing the test of time, 50 years down the line, a Binishell remains atop Mount Etna in Sicily, constructed to protect seismographs through earthquakes and eruptions.

All in all, it’s clear that Nicolò is a man on a mission to play his part in making the best of what nature has to offer, to contribute in a meaningful way. When I asked him what sort of legacy he’d like to leave for his two daughters, he pondered for a second before responding, “The Dalai Lama said that the most direct way to happiness is right intention. And that is so powerful. What that says to me is, the most effective way to get to what we all want is simply to approach things from the right point of view, to listen to your heart.”

Learn more about Binishells here