James Brown is a magazine maverick, legendary journalist, esteemed author, and some-may-say-madman. Not only did he ride the cultural zeitgeist of the 1990s, he was leading the charge, writing the story, reviewing the theme tunes — the punk pied piper for a generation of young British men.

Starting out selling homemade fanzines up front at local gigs, he longed for a life beyond the perceived limitations of his upbringing in Leeds, in the north of England, amid the financial and social turmoil of the late ’70s and early ’80s. Possessing bags of talent, addicted to excitement — and, before long, to booze and drugs — he became the youngest features editor of the revered music bible NME in 1988, at the age of 22. Writing over 50 cover stories, he championed (and partied with) bands such as The Jam, The Beastie Boys, KLF, the Happy Mondays, and many others.

Then in 1994, aged 27, James created the revolutionary magazine loaded, unleashing the first ‘lads’ mag’ on Britain which changed the publishing industry — and the country — forever. Gonzo writing, inspired by his American New Journalism heroes Hunter S. Thompson and Tom Wolfe, was combined with features with a distinctly British flavor (The World Cup of Crisps!). As James wrote in the first issue, “loaded is a new magazine dedicated to life, liberty and the pursuit of sex, drink, football and less serious matters.” It was a potent cocktail, and was as transformative to the UK pop culture landscape as MTV had been a decade before.

Winning a succession of awards, James notoriously hung-out in the live-fast-die-young-lane, traversing the globe on a diet of music, sex, fashion, drugs, booze, racing cars… and crisp sandwiches! His extraordinary drive, fueled in part by the tragedy of his mother’s suicide, saw him go on to become editor of British GQ at the age of 31, where he launched the publication’s prestigious Man of the Year Awards. But his extreme lifestyle and declining mental health soon began to catch up with him. It was time to take stock, to get sober, to seek help — so after two years atop the masthead, his publisher Condé Nast supported his trip to rehab.

Now a 57-year-old father-of-two and 25 years sober, James has reflected on his high-octane journey in his riveting memoir Animal House. James lived on the edge — beyond the edge — and his unapologetic, outrageous approach helped define the ’90s, and made him the voice of a generation of thrill-seeking young men. And he is now helping members of that same generation follow a different path — finding new meaning as they turn the page on the debaucherous lifestyle of their youth.

“Particularly at loaded, we flew the flag for excessive behavior,” James recalls. “There was an irresponsibility in our encouragement to get people to drink and take drugs, and frankly it was because we were having a f***ing great time doing it.

“And so, in the book, I make a point of explaining a little bit about how I was able to move away from that, and just say that there’s another way. You don’t have to be fat, 50 and f***ed. You can get a new sense of awareness of a life to come.

“I get a lot of calls saying, ‘Can you talk to my son?’ Or, ‘My wife’s not in a great way with her drinking.’ Or whatever. So I just talk to people for a little bit, and then I’ll send them the way of the people who help me, the professionals.”

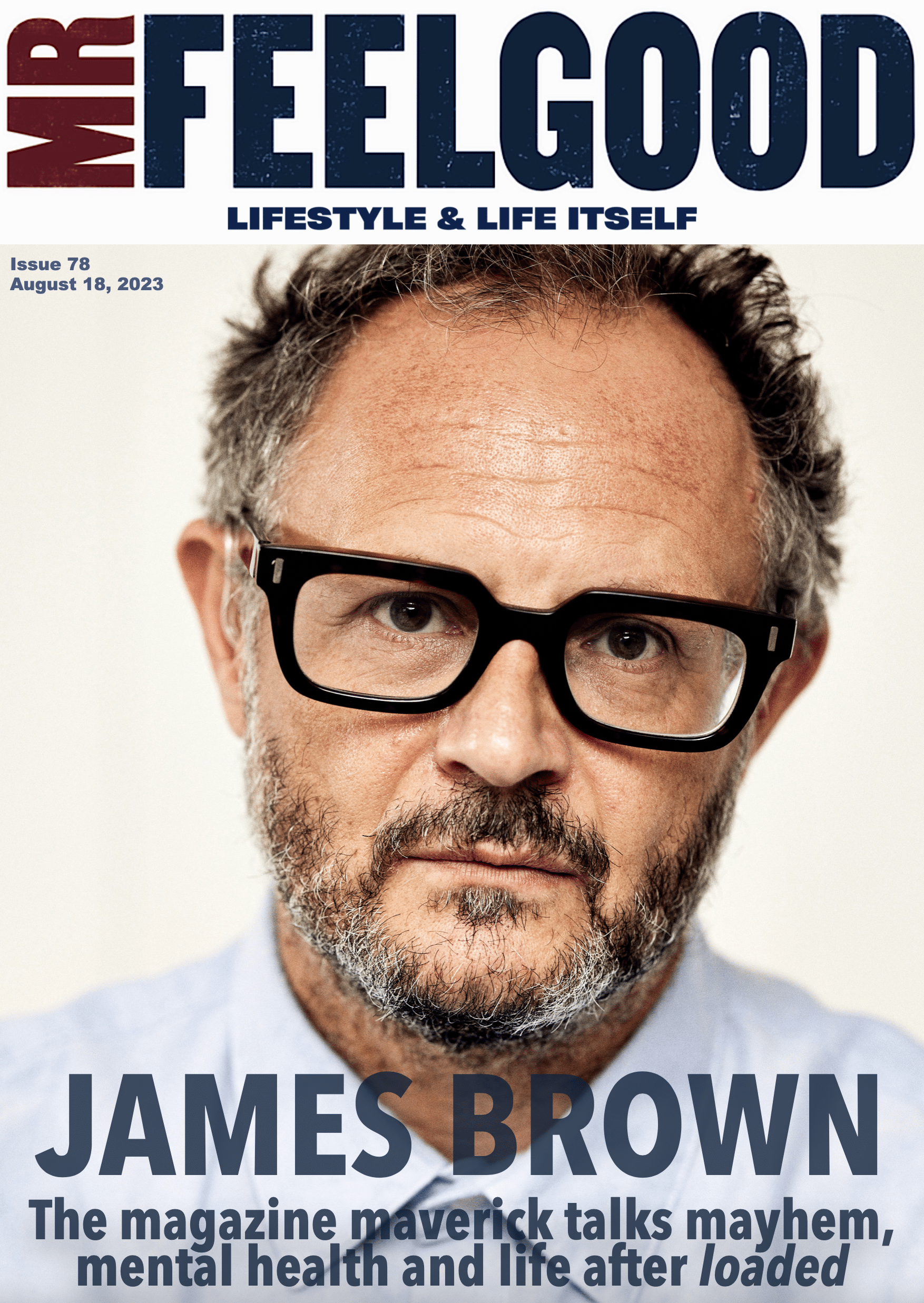

When we recently met with James in South London, we found a man in rude health, still with a sparkle in his eye, a sharp mind, and a wry wit (and forever a Leeds United fan, of course). And he’s now also in possession of a hard-won wisdom, maturity, and grace. He even turned down an Earl Grey tea on arrival at Tuckers Yard studio on the grounds it might make him “too punchy” — such is his body’s sensitivity to stimulants these days.

And this iconic trailblazer for youth culture is now championing some good, old-fashioned values — like going beyond the shorthand of social media approval to support our friends or peers. “No-one calls each other anymore. Picking the phone up and talking to a mate only takes a minute, but might be a thousand times more helpful than getting 100 likes, hearts, or retweets.”

It was this pursuit of real connection that led to James becoming this week’s Mr Feelgood cover star. After discovering our publication online and enjoying the content, he took the time to make contact with us to congratulate us on the platform we had built.

“I like the fact that you focus on positive things,” he says. “Because actually — although we were being very self-destructive — if you go back to loaded, it was like a fanzine. We never ran anything that slagged things off. I kind of got sick of that at the NME, the cynicism. So I love the positivity.”

So we are honored to welcome James into the Mr Feelgood community as the latest subject of our Who the F*** Are You? profile. In our interview — available as a video or podcast, or in written form below — we speak about the process of writing the veritable page-turner Animal House, including the challenges of sharing the very painful truth regarding his mother’s mental health battles, his own struggles with addiction, and the embracing of a new chapter. He’s now an in-demand creative consultant and public speaker, still a passionate and revered journalist — and very happy to be alive.

“I realized the other day I’m not in conflict with anyone,” he says. “No work-related conflict. Not in conflict with the council! Not in conflict with anyone. And it’s incredibly refreshing to get to that point.”

Who the f*** are you?

I’m James Brown. Libra, defensive midfield, dad, football fan, writer, former editor. But probably the most pertinent thing is alive.

When I was young, I never envisioned I’d be somebody who would be alive in their 50s. It wasn’t a narcissistic, self-destructive plot or an affectation. I just didn’t. When I was first on the NME, I had no concept of even being in my 30s. Sometimes success can kill people, as is well documented in the music industry and the film industry as well. So for me, I am glad I’m here and I’m glad I calmed down a bit.

It’s been interesting revisiting [my achievements] in my book [Animal House]. It was really difficult writing the book. It took me about six, seven years. There was a mixture of having access to some great music scenes, and then having my own equivalent of what felt like a rock and roll success with loaded. They were really intense, exciting times.

But then at the same time, I’ve written about some very personal stuff that was going on in my family. My mum took her own life when I was 26 and had been ill throughout the time that I’d been a writer. It was difficult to write about that alongside what it was like to be backstage with the Happy Mondays and George Michael at Rock In Rio in Brazil in ’99, or testing crisps, or getting awards. Just writing the truth of what had been going on in my life, rather than what I was projecting and what I was very busy being noisy about out front, was incredibly difficult.

From an early age, my dad explained how the world was unfair. Not in a bitter way, but from when I was really young, he was talking to me about politics and I wanted to make sure that perceived unfairness was not going to f*** up my life. I wanted more than what was on offer. And I wanted to achieve that by doing things that I loved. I didn’t want to have to sacrifice my passions and interests. Some people give away what is important to them to get somewhere. I didn’t want to do that. So that really was, for me, the success of my life. I was able to spent about 30 years doing things that I would’ve done for free, and getting paid quite a lot of money for it.

How are you feeling right now?

I feel great. Getting rid of the book has given me a sense of freedom.

Where did you grew up and what was it like?

I grew up in a place called Headingley in Leeds, which is probably best known for being where England and Yorkshire play cricket. England just had a test match there against Australia a couple of weeks ago. There’s one particular [camera] shot, looking towards the Kirkstall Lane end, and you can see the streets I grew up in. It was a strange mix of red brick terraces and quite leafy streets. It was full of little kids then, but it’s now a student area. And that’s where I spent my childhood. It was fantastic. We lived on sweets, white bread, crisps, and chips. We lived to play football before school, during school, after school. We were in the woods, in the park, in the streets with chalk goalposts.

It was football, all the time. When I was growing up, Leeds United were the best team in the country. So that was great. Before I lived in Headingley, we lived in this place that I call the footballer belt, Collingham, where a lot of the Leeds United players still live. It’s quite a posh area. We lived there for a couple of years, and my hero then was living opposite me, Alan Clarke, the England and Leeds centre-forward. His wife and my mum were good friends. And I think that gave me, without realizing, an understanding that fame and success could be next door. It wasn’t something that was intangible, that only happened to other people.

Then what happened was, in my mid-teens, this beautiful scene — riding bikes around, listening to Radio 1, T-Rex and then a little bit later punk and new wave — it just all started falling apart. Where I lived, we had a serial killer who killed 15 women — Peter Sutcliffe, the Yorkshire Ripper — and two or three of the attacks were right where I lived. One of the attacks was a woman staying at my girlfriend’s house. His victims were women, they were mums, sisters, and daughters. For the whole city, it just gave a tremendous and a terrible sense of fear, paranoia, and darkness.

And then we had mass unemployment in the early 1980s. As I was approaching leaving school, I didn’t know anyone who had a job. My parents were split up, my mum was ill. It went very dark. So quite early on in my book, I say this is a story about two childhoods. And in a way, the childlike nature of a lot of the stuff we did at loaded — which was one of the first times anything in the British media was fun and funny, previously it was all quite uptight — was my interrupted childhood revisited.

What excites you?

Excitement! Years ago, when I was on the NME, somebody said to me, “You’re not really into music, you’re into excitement.” And he was half right. Obviously, I was really into music. But I liked the excitement. My first real sense of hyper-excitement was being down the front of gigs. So these would be bands like Skids or Stiff Little Fingers or The Jam or The Undertones, The Buzzcocks, The Specials, those kind of bands that emerged after the initial wave of punk. Just jumping up and down until my ears, which are now f***ed, were ringing for days on end. I like driving fast. I love football, or what the Americans would call soccer. I like walking around the countryside. I like a lot of shit, you know?

What scares you?

Well, I’ve thought about this question. There’s kind of three answers to this.

One, there’s the fine line you carry every day as a parent where you cannot let fear override your concern and hope that your children are okay. You have learn how to manage that, have a degree of acceptance.

And then growing up I was super-fearful. I’m sober now and 25 years clean, but for years I lived with this utter fear. A lot of other recovering addicts and alcoholics I’ve spent time with [also experienced this]. What I came to realize was that I was scared of myself. But that isn’t there anymore. That’s gone. I realized the problem was me. I would walk home from the gigs down the middle of the road, paranoid that someone was going to leap out. There was nothing there. Nobody was going to leap out at me. The fear was purely self-constructed.

Then the third part of the answer is I think I’ve been absolutely f***ing terrified four times in my life. One was jumping out of a plane. Six months after I got clean, I was really depressed. I was editing GQ magazine and somebody asked if I wanted to do a skydive. I felt so bad at that point. The rehab therapist was saying, “You need to jumpstart your nerve endings.” The coke had stopped me being able to generate serotonin. So I thought, “Okay yeah, I’ll do a skydive. Then if the parachute doesn’t open, I’ll be better off anyway.” So that was terrifying.

I was once on a horse that bolted. And the strange thing is, when you’re in that scenario where you’re going to get hurt, everything kind of slows down. It’s amazing how much time you’ve got to work out how painful it’s going to be when the horse jumps over that stone wall we’re heading to and fires me into a forest.

Then I was in Africa and our guide drove in on two lions that were having sex. The guy was a f***ing idiot. He should have just left them alone. He went closer and closer, and then he got the front of the truck stuck under a tree. The f***ing lion was so furious, as you would be. Imagine if you were having sex and a bloke brought a load of lions to look at you! The lion came over and went round and round this truck we were in. The guide managed to get us out and drive away very fast, and that was when the fear kicked in.

And the other time I was on a boat with my little boy, doing a really rough crossing in the Caribbean, on the way from St. Vincent to Bequia. It was so rough that I started planning what I was going to do when we go over. I kept my kid close. We hit a wave. At one point the captain fell over. There was only one engine. The life jackets were like 100-year-old pillows, they didn’t offer much in the way of support or encouragement. When we got to the other side, my little boy said, “Daddy, were you scared?” I thought, should I tell him? I said, “Yeah. I was actually, I was really scared.” He said, “So was I, and then I just imagined we were in an army game.” He was about seven at the time.

I find it interesting reading stories about people who have been in proper conflict situations, war situations or whatever, and how they have to adapt. Then how they struggle [when they get home] because of your antenna is on such full alert.

What’s your proudest achievement?

Probably The Crisps World Cup!

When I was thinking about these questions, I was thinking, shall I answer these seriously or shall I be flippant? This sounds strange, but I once stamped on a soft drink can, and it flew up into the air and I volleyed it into the bin. It was like something they would’ve got Mbappe to do for an advert, and shot it many times and maybe green-screened it and digitally enhanced it! We had a semi-pro footballer working with us at that point. He just looked at me like he couldn’t believe what he’d watched. And the trick is, if you ever do anything like that by accident, definitely don’t try to do it again.

Things that make me happy are when people come back to me and say, “You took a bit of time to talk to me 15 years ago and it really helped me.” A lot of them are people who have issues around drink or drugs. You’re not doing it because you want to be able to be proud of it, you’re just doing it to pass on the good advice and to help. So that makes me feel good, just to talk to someone and point them in the right direction of how to get help. You don’t think anything more of it, but for them it might be a start to get into a better place.

And my kids.

What’s the hardest thing you’ve ever done?

The most difficult thing was living after my mum died. Not staying alive, but living with those feelings.

That’s an instinctive answer. I was going to say getting clean. But if you lose a parent or a child to suicide, it’s an interruption of the natural order of things. When you get a call saying your mum’s dead, and she’s taken an overdose, that was the most difficult thing.

For a long time, when I got clean, I started associating with other recovering addicts and alcoholics. You heard this phrase that they were slowly committing suicide. That’s what their drug addiction or excessive drinking was. And that was something I’d always felt like I was doing with that stuff, but I’d never articulated it.

But that was the most difficult thing and it was difficult to write about. It’s not just my experience, it’s other family members’ experience too. So I was nervous about that. When the book first came out, one of the first things I did was talk in London at Soho House. I found myself getting really, really emotional and I realized I’d never done that before. And it helped. Because I’d talked about these things in a room with a therapist or in a room with other recovering addicts. But I’d never opened up like that.

So that is probably the hardest thing, as I’m sure it has been for many people, coping with an immediate relative’s death.

Who was your greatest mentor and what did they teach you?

I was reading your interview with the guy who played Gus Fring in Breaking Bad [Giancarlo Esposito] and I thought that was a brilliant story about him having a mentor who didn’t know he was his mentor, Sidney Poitier. And I think we all have those, they’re called heroes, aren’t they? People who influence you into do what you’re doing.

My dad was great. When I was about nine or ten, I remember being on the back step in the garden in Headingley, and him pointing to this terrace house behind, which was two up, two down, and saying, “You can do anything in life. You could jump over that building if you want to.” Which obviously I couldn’t, but the point he was making is don’t limit yourself. And unfortunately, there were Hell’s Angels lived in the building that he pointed to, and one of them did go over the roof on angel dust!

My dad basically spent a lot of time telling me, “Don’t accept any shit.” He was from quite a poor family, in a small stone house in a village, three of them in the bed. Because he was bright, he’d gone to the grammar school, so he’d been in that scenario of feeling out place. And I think the difference is, I never felt out of place. I felt like I’ve got every right to be where I am.

In the early years, when I was starting to meet musicians and things like that, I was so cocky and confident, people would often think I’d been at a public school. But obviously, I went to a comprehensive school in inner-city Leeds. And so, no, I’m just like this — unfortunately, for the people around me!

Then at work, there was a guy called Alan Lewis, and he was an editor on the NME. Alan really encouraged me, and he made me the features editor of the NME when I was 22. Not long before, I’d thrown up all over his desk, I’d punched one of the writers. I was not very socialized, I’d never had a job before. I’d worked in a record shop and done a milk round. I had no understanding of how to talk to people. He could see that I knew about the new wave of music that was going on, he could see I was pretty good at writing about it, and also that I knew lots of writers. At that time, the NME was the most influential music weekly in the world. If you were a young act, Sinead O’Connor, or The Charlatans, or The Stone Roses, or whoever, and you got on the front of the NME, that was it, people all over the world that looked at British music or Irish music would be receptive to that. Then later, Alan was the guy that got IPC, who were known as the Ministry of Magazines, to launch loaded. So he was my professional mentor, really.

He died two years ago and I spoke in his garden afterwards. What I liked about it, and it made me think about my own life, was his garden looked immaculate. I said, “Who did all this?” And they said, “Alan.” I only knew him as an editor and a drinker. They did these slides of his life. He’d had this whole post-retirement life where he traveled all over the world with his wife. I liked the fact that I didn’t know anything about that, and I was surprised by it. Too many people’s lives are purely defined by what they do professionally, and he had this whole other thing going on beyond being our boss and our father figure.

I was very thankful to him because he changed my life twice, really. Just backing me, supporting me and promoting me at the NME, and then offering me the chance to create my own magazine, which was loaded.

Who are your fictional and real-life heroes?

Myself! No, my real-life heroes are easier to say. I didn’t go to university, I went to the bookshop and read, or to my dad’s bookshelves. I read Hunter Thompson, Tom Wolfe, and they were two writers that made me realize you might even be able to make a living out of writing, and do it in a way that was fantastic and amazing. They were my heroes and my inspiration.

Their writing sounded like the things they were writing about, so when Hunter Thompson was writing about Hell’s Angels, it felt like the words were revving up and firing off the page.

I met Tom Wolfe, and I tried to meet Hunter. Then later I was glad I didn’t. Hunter rang the loaded office once, screaming and shouting , “You guys have been ripping me off!” That was pretty exciting!

Fictional heroes… There’s is a writer called James Lee Burke, and he has a character I like called Dave Robicheaux who was a detective. I named my book Animal House, and I love [John Belushi’s] character, Bluto, in that film.

What’s your favorite item of clothing in your wardrobe?

It’s the Nigel Cabourn parachute material jacket that I’ve worn in a couple of these shots. I love that. I bought it in Japan.

What music did you love age 13, and do you still love it now?

I was 14 in September 1979, so I was 13 for most of that year. The amount of brilliant records that came out in 1979… from Blondie, Elvis Costello, Joe Jackson, Skids, The Buzzcocks, The Specials. It was just an amazing year. That was probably the year I started going to gigs as well.

I think the regeneration of music through younger members of the family is interesting. When my eldest was in primary school, I remember him coming home and asking, “Are you Blur or Oasis?” This would have been in 2010, when both the bands had kind of been and gone.

I know Spotify’s been a problem for the artists because the royalties are so low. But as a user, I like the fact that you can put in a few songs and then they’ll take you off. I like Fontaines D.C., they’re the last contemporary band I saw live. They have that energy of the sort of bands I used to write about, without sounding retro.

And yeah, I do occasionally listen to the things that I listened to when I was 13. But because I’ve got hearing aids, I can’t use earbuds!

What is the most inspiring book you’ve ever read?

Probably The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test [by Tom Wolfe]. It would be those books, by the American New Journalists that I was talking about before. Things like Dispatches by Michael Herr. Those books that brought the novel form of reporting, they illuminated the possibilities. In my book, I explained that when I told the careers teacher at school I wanted to be a music journalist, they suggested I become a printer. So, that’s what you were faced with, because they didn’t understand that you could go out and do this sort of thing. So reading those books absolutely changed my life.

What is a movie that left the lasting impression on you?

One, when I was really low after my mum died, was Bad Lieutenant. It’s obviously not a feel-good film, it’s about a person in an advanced state of collapse. But I saw that at a time when I was really struggling, in Haymarket in London. I left the NME, I broke up with my long-term girlfriend, and then my mum died. And I was writing quite a lot of articles about man, not at his worst, but not at his best. I was trying to find places to put these pieces, and some people wanted them, and some didn’t get what I was writing about. And that, ultimately, was one of the motivations to create my own magazine. But I came out of that film, in a legitimate cinema, and it was so full-on. That gave me some inspiration that if you want to do something that is different and a little bit hardcore, a little bit out of the norm, it can be done.

Then the other film that I really liked for years was Withnail and I. I wrote the first piece that recognized that Withnail had become a big cult. That was in the first issue of loaded. So I love that.

I also love Taxi Driver. All three of those films are about loneliness, really. I think although I knew a lot of people, if you’re not at ease with yourself, you’re not going to be at ease with other people. Or if you’re not at ease with yourself, other people aren’t going to be at ease with you. And I was aware of how aggressive I was as a kid and as young man. After my mum died, nobody was in a position to share their experience of that. My mum and dad had been separated. I don’t remember a lot of conversations about it.

And there’s a professional loneliness. You want to achieve something, you want to be able to get to a point where you’re doing what you want to do. And luckily for me, I found that. When I was on the NME, that’s what I wanted to do. But it was so f***ing intense, it wasn’t actually all that enjoyable. I thought I was leading a division in a music war. That’s John Peele, that’s daytime radio. They’re all f***ing shit, these are all great. It was so intense. Then I’d come home and I’d get a call saying, “Your mum’s thrown herself off the f***ing roof.” That was hard.

Having said that, I spent a lot of time at the Hyatt on Sunset, thinking I was Robert Plant, drinking margaritas, or snogging girls in New York and so on. So it was good fun!

What is your favorite word or saying?

A phrase that I heard in the process of learning about staying clean and sober is, “You keep what you have by giving it away.” That you maintain the things that you learn about, the more you tell people about them. I like that. It’s a very simple idea that you share the good things that have benefited your life — mental, emotional, spiritual or whatever.

What do you want people to say about you at your funeral?

Not so much about me, but about the funeral: “Where’s the food?” I don’t really give a f***, I’ll be dead.

I’m a big believer that you should do things for people or tell people things while they’re alive. I think nowadays we feel like we’ve communicated with somebody when we’ve clicked like on an Instagram post, and a few months ago, I thought, “I’m not going to do this solely anymore.” If I see a picture of a guy on a beach with his kids, I’m going to pick the phone up and go, “It looks like you’re having a great holiday.” Or, “It looks like your life’s great now you’ve moved to Devon.” Because particularly as you hit your 50s and your 60s, people are going.

Quickfire five favorites…

Car?

I’ve been banned for a while. You don’t need a car in London.

Sports team?

Leeds United.

Meal?

Sushi in Japan. At the docks in Tokyo.

Grooming product?

Well, it used to be Chablis. It’s funny, when we did loaded, [the grooming companies] always wanted to advertise. I never wanted that stuff in the mag. I used to think grooming was the horses. And then, sure enough, as you get older, you think, “I wonder if I could tighten this stuff up here.”

But probably the best grooming product I’ve had recently would be Ozempic. It just f***ing works. Jab it in, the stuff drops off. But there’s a shortage now. That’s sort of grooming, isn’t it?

Clothing label?

The first time I was really aware of clothing label, it was Paul Smith. Paul is such a brilliant character, an inspirational figure. As a kid it was Adidas t-shirts. But now I get t-shirts from places like Sunspel. And Nigel Cabourn, I like his shop in Tokyo.

Learn more about James’ adventure in Animal House

Photography Assistance by Mark Townsend

Thanks to Rick Truscott at Tuckers Yard

James shares his top seven magazine covers here

James has been an inspiration to me and many of my friends. Good on him for pushing forward