In the fantasy world of Douglas Adams’ 1979 novel The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, the number 42 represents “the meaning of life, the universe, and everything.” And the number has become the subject of fascination for fans of the sci-fi franchise ever since.

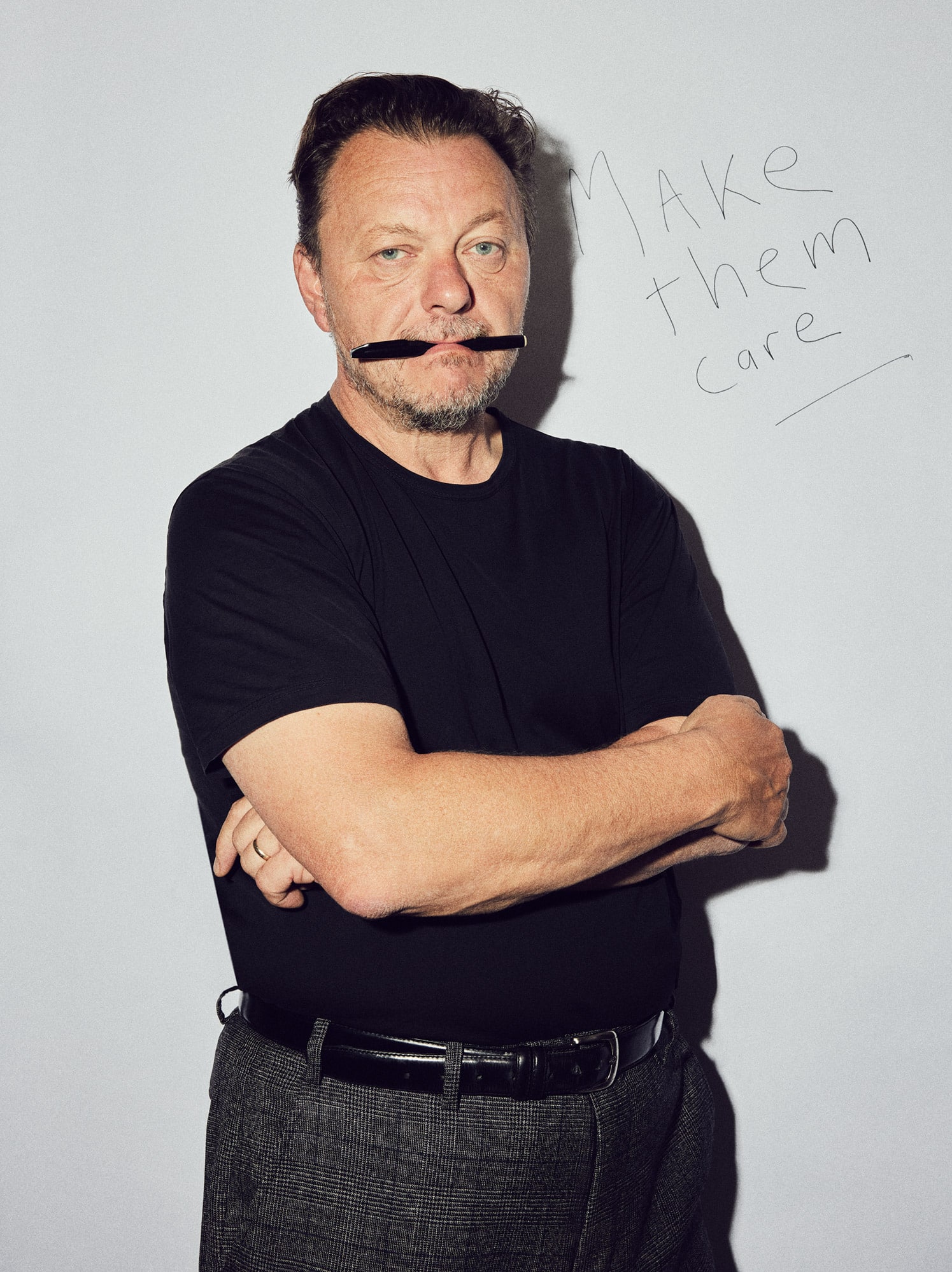

Back in the real world — Ayshire, Scotland, to be precise — the number carries genuine weight for John Niven, an author and screenwriter adept at skewering the absurdity of life on earth. It’s the age that his brother, Gary, killed himself. And, he believes, a critical time of life for all men as we deal with the mental health challenges that can come at this tricky fork in the road.

“Forty-two is a real peak zone for male suicide,” John explains. “I think that’s because you’re still quite young, there’s a lot of road left to run — but you can feel like there’s nothing good for you left down that road.

“In the Navy, they used to do something called breeches buoy transfers. If they had to get a doctor from one ship to another in the war, they would put them in a little cage and shoot them along a rope. Sometimes the waves would be so massive that they couldn’t see the ship they had come from, or where they were going.

“I think that’s a bit like your early 40s. You’ve completely lost sight of where you came from. The glory days of your youth are quite far behind you. But you have no idea of where you’re heading, and what you’re going to do for the rest of your life.”

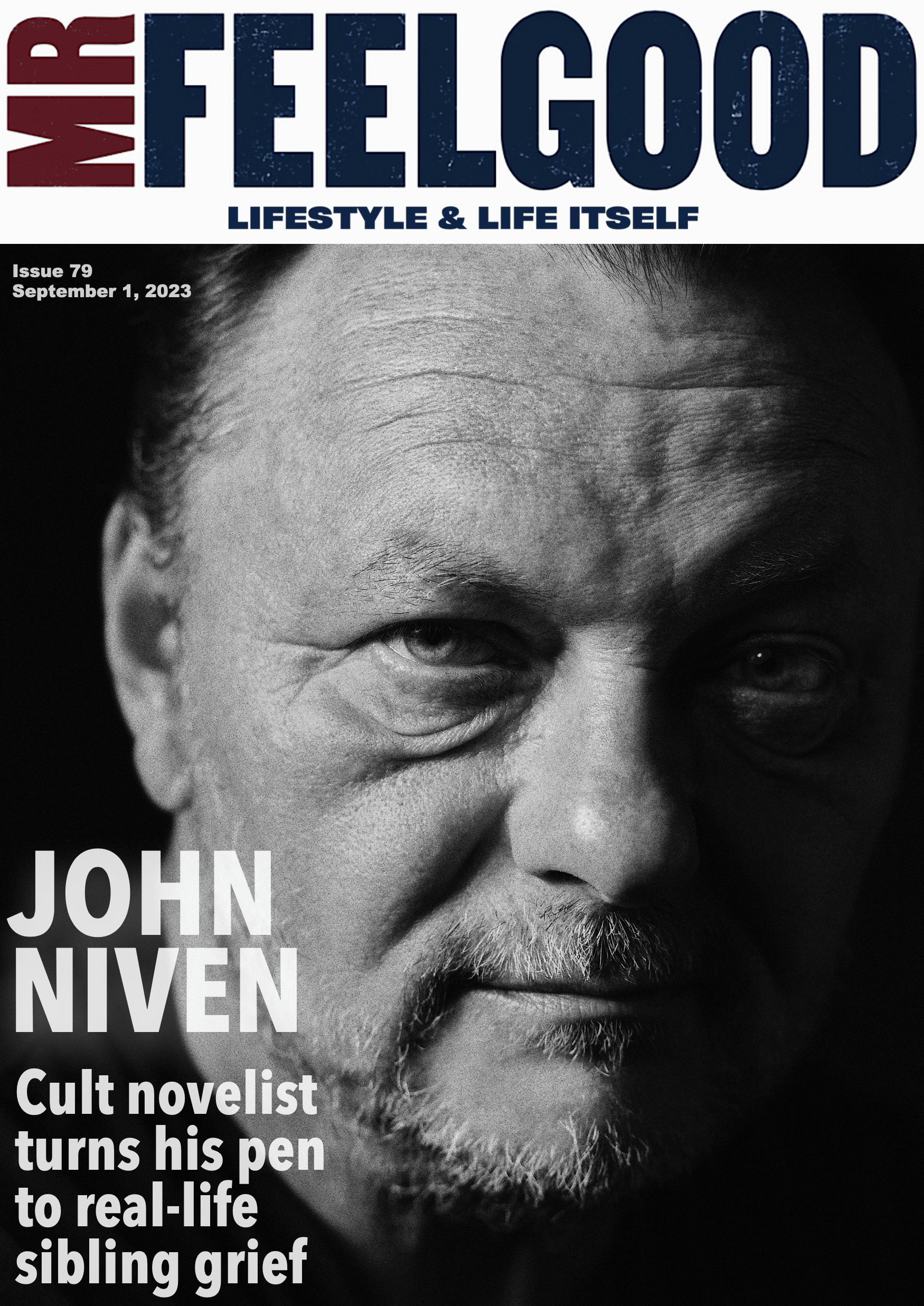

Speaking to John a few days before my 42nd birthday, his words really resonate with me — as they have throughout his prolific writing career. We have never met before this Zoom conversation; me in my Los Angeles office, John in his Scottish homeland. But his delivery — punchy and punky, perversely poetic — is very familiar. I was obsessed with John’s debut full-length novel, Kill Your Friends, when it was released in 2008; a scathing satire of the murky London music industry that he had previously worked within as an A&R guy, and I was covering at the time as an entertainment reporter. (John admits he was lucky to have his writing talent to fall back on, since he passed on signing Coldplay and Muse during his time as a record exec!)

John, like myself, has turned his professional attention to men’s mental health in recent years, writing his first nonfiction book, O Brother, which is part memoir, part soul-searching study of his brother’s life and eventual suicide. The black humor and tales of drugged-fueled adventures that are staples of his best-known novels still swagger through the pages, but mixed with a maturity and vulnerability that makes for an incredibly honest examination of family and grief.

“With suicide, you become a PhD in the subject after the event,” says John. “My brother was unemployed; he was living alone; he’d had a relationship breakup; he had financial difficulties; he had a history of drug and alcohol abuse. There were red lights across the board. But I didn’t really know how to look for them.

“If you know somebody in that situation, you might want to keep a closer eye on them. We think we ask people how they are doing, but often we just strike a match at the mouth of the cave, and take a little peek in. We don’t really get in there.”

O Brother is structured around the three long days that John, his sister Linda, and mother Jeanette spent sitting around Gary’s bed in Crosshouse Hospital, East Ayrshire, Scotland, where he lay in a medically-induced coma before his death — using that experience to jump back into stories of their lives that led to that point.

Gary, an unemployed carpenter, had called emergency services in the early hours of August 31, 2010, and told them that he was depressed and worried he was going to take his own life. He was driven by ambulance to hospital, but as he waited for a doctor to see him he hanged himself in his accident and emergency room. He died on September 3.

In the book, John describes a period of his own life — in his late 30s, not far from that fabled 42 — where he experienced suicidal ideation. He writes about struggling to shake off his “former life of hedonism and current one of failure” while living with his mother-in-law in leafy Buckinghamshire, England, as an unpublished author. His adventures as a big city music exec — with its cast of highly entertaining characters of questionable moral judgment — offered some great writing material, but was no longer paying the bills.

Now 55, he credits his passions, hobbies, work, and home life with keeping him a safe enough distance from the edge. “I was fortunate that I became a music obsessive in my teens,” John says. “I played guitar, I read, I loved cinema. And as you get older, you realize these are all reasons for living. Stuff you can fill your soul with. I also had a busy work and family life. Put all that into the pot and it’s a pretty full day — you don’t have much time to sit and dwell. My brother ended up with no real interests or hobbies, no family, and no job.”

John’s debut novella, Music from Big Pink, was published in 2005 to warm reviews. But his darkest days came in the couple of years that followed, as he continued to strive for that elusive publishing deal. “During that period between leaving the music business and my first book coming out, I wasn’t being lazy,” he recalls. “I would get into the study at 8am and write until late afternoon. The journalist Malcom Gladwell says you have to put in 10,000 hours to achieve excellence, and I think I did close to that in those years. But there was no certainty it would pay off.”

His hard work was eventually rewarded when Random House agreed to publish his debut full-length novel, Kill Your Friends, which became an instant cult classic on its release in 2008. “The most exciting British novel since Trainspotting,” were the words of one respected reviewer, and echoed by readers across the country — many of whom, including me, were men in their 20s who took a break from their vampire-like social lives to devour their first novel in years.

“I was a writer in my bones from a very young age, but I ran away from it for a long time,” John says. “My ex-wife bought me Stephen King’s book On Writing when I was leaving the music business, she knew me better than I knew myself. That was a great motivation.

“There’s a line in that book where he says something like, ‘The muse is much more likely to show up if it knows where to find you.’ I tried to write novels throughout my late teens and early 20s, but they all just fell apart. I expressed myself in the same way, and could have written you a similar sentence to what eventually made me successful. But I did not have the self-discipline to sit at my desk and shut the door behind me for five or six hours every day for the six months it takes you to write a draft. And then, the worst part — go back to page one and rewrite the whole thing.”

John tells me that Kill Your Friends took 12 drafts to complete, while his more recent novels tend to get finished in three drafts and a polish. But O Brother was a return to a much longer operation, dissecting his memories and grappling with the new challenge of maintaining his own authentic voice, rather than that of a fictional character, throughout his story.

In the book’s opening chapter, he describes how the process was like interrogating “an identity parade of former selves” — all with their own unique haircuts, dress sense, and secrets. “Because that’s what it feels like to me, the memoir,” he writes. “A forced confession.” And when John lined up these characters, he discovered the studious 13-year-old version of himself was now more recognizable than the 27-year-old “waving the champagne bottle above his head as he danced on the balcony of the Chrysler Building, howling at the New York moon, blitzed in cocaine and Quaaludes.”

He ended up rediscovering that self-discipline of his early teens — “before I discovered punk rock, and blew it apart” — to build his future. “Real change is very difficult and scary,” he tells me. “It takes real effort. When I started really trying to write, I was in my 30s, in London, and still living the life I had been for a long time.

“You need a lot of self-confidence and self-belief, especially as an unpublished author. I can’t have that when I’m crippled with a hangover. So we moved out of London, and for the first few months I wondered what the f*** I was doing. All my mates were still living the life in London. There was a lot of financial pain, and I felt very uncool, suddenly living out in Buckinghamshire with my mother-in-law.

“But I gradually got into the work. I was living a much healthier lifestyle. And it all paid off. Scott Fitzgerald famously said, ‘There are no second acts in American lives.’ Well I managed a fairly successful second act reinvention, thank God.”

John’s brother Gary never managed that second act, nor a neat ending. The cause of suicide is always more complex than the survivors crave, especially when there’s no note, as was the case with Gary. But one central detail leapt out of the page as I read John’s 384-page search for reason and meaning.

Gary was a sufferer of cluster headaches, a rare condition that affects less than 0.1% of the population. John is also a victim of this debilitating disorder, which is considered the worst pain known to man or woman. As am I.

Cluster headaches tend to attack on one side of the head, behind the eye — a crippling, searing pain lasting around 30 to 90 minutes on average. Their name comes from the fact they come in clusters, affecting episodic sufferers every day, or multiple times a day, for a period of time before a period of remission. And they follow a circadian pattern, normally occurring around the same time of the year and the day.

My clusters began when I was 28, almost 15 years ago. They strike every Spring and Autumn, lasting for a few weeks, which is quite a common pattern for episodic sufferers. John has been a little luckier, with his pain-free periods between attacks lasting many years. But Gary was one of the unluckiest of this unlucky 0.1%. His attacks were chronic, hitting him multiple times a day for many months on end without respite.

When you meet a fellow Clusterhead — as some like to be known — you have a lot to talk about. Beyond chatting on internet forums, I think I have only previously met three other sufferers in my life. So John and I quickly begin exchanging war stories.

“Mine started when I was about 37,” he explains. “I woke up one night in agony. I had a splintering pain behind my eyeball. It passed after about 40 minutes, so I went back to sleep. Then I woke up again about an hour-and-a-half later and the same thing happened again. After a few days of this it got to the point I was afraid to go to sleep, because that was when they were coming on each night.

“I started googling and I came across a website called OUCH — the Organization for Understanding Cluster Headaches — and I realized that’s what I had. But I’ve been pretty fortunate so far, in that my headaches are episodic and quite rare.

“My mother had mentioned to me once or twice that Gary got bad headaches, but I didn’t take too much notice of it. Then in 2007, my sister rang me to say he was talking about suicide and in agony with his head. He went chronic, and would have ten headaches a day, every day, for months without remission. Doctors called them suicide headaches back in the ’50s and ‘60s, due to the pain. Women sufferers say it’s worse than childbirth.”

John managed to get his brother to a specialist in London who prescribed him the only effective – legal – treatment, which is to breathe oxygen from a tank during an attack to ease the pain. But there is another treatment that most doctors won’t tell you about, that you have to learn about on Reddit or Facebook groups — psilocybin, the active ingredient in magic mushrooms.

Treating cluster headaches with mushrooms is known as ‘busting’ in these digital communities (providing the moderators don’t shut down the chat). Sufferers share the trial-and-error regimens they have landed upon to get rid of the headaches without getting too out of their minds. For many, taking mushrooms at the onset of a cluster period — when mild headaches known as ‘shadows’ begin, but before the more painful attacks have kicked in — can halt the headaches in their tracks and stop them returning for months or even years. A popular ‘busting’ routine is to take one dose of around one gram of mushrooms — which is a mild to moderate recreational dose, enough to experience some psychedelic effects — followed by two smaller doses of half a gram, taken five to seven days apart.

Even John — familiar with the world of recreational drugs from his previous life as an A&R exec, and diving for clues on the deep web in his current one as an author — wasn’t aware that psilocybin was a possible, potentially life-saving, treatment. Fascinated, he makes a note to go away and research. Hopefully, a mushroom-chomping cluster sufferer will be found tripping in one of his upcoming novels or scripts, bringing much-needed attention to this wildly under-researched and misunderstood condition.

“I think it did become key,” John says, referring to the role the headaches played in his brother’s death. “Like all these things, I think there were a lot of other factors in the mix. But I think he couldn’t see a light at the end of the tunnel with these headaches.

“They say the average time to proper diagnosis with cluster headaches is seven years, and my brother must have been at least five. He was a working class guy, and wasn’t very articulate, so he’d be describing these headaches vaguely to the doctor. And he would trust anybody in authority, rather than question their diagnosis. So the doctor would just give him these huge Nurofen tablets — but taking a Nurofen for a cluster is like shooting a pea-shooter at an express train. Totally useless. It’s a hellish disease.

“He couldn’t really manage the condition on his own, and stay on top of keeping his oxygen tank filled. And he was self-medicating with weed and smack. He was one of those guys that just keeping his life on the rails — paying his tax, bills, mortgage — was too much.”

O Brother is John’s tenth full-length book, and he has also enjoyed success as a screenwriter, adapting Kill Your Friends for the 2015 movie version, starring Nicholas Hoult as the murderously ruthless A&R man Steven Stelfox. Other screen projects include co-writing the script to the 2019 coming-of-age comedy How to Build a Girl alongside journalist and author Caitlin Moran.

One of the things that strikes me most about O Brother is the precision of John’s memory, even when recalling incidents that took place when he and his brother were schoolboys, or a little later in life during hazy booze and drug benders.

“I think as a novelist, there’s a part of you that is never fully in a scene,” he says. “You are always standing back a step, looking at what is unique and funny about a situation. I think a lot of people have that when they’re teenagers. As novelists, we never really grew out of that teenage awkwardness and fascination with the world.”

Now, that same curious and perceptive mind that made John one of his generation’s most successful fiction writers has helped him craft O Brother, a thorough and thought-provoking examination of the life-and-death importance of mental health.

A perfect 42nd birthday gift.

O Brother is available now

Photography Assistant — Morgann Eve Russell

Retouching — Mike Harris @ NOKK