Some of us know how it feels to train for a sporting or endurance event, only to have all our sweat and toil wasted when we’re hit by an injury before the big day. Or perhaps we’ve just had our favored regular exercise scuppered by a sprain or strain we didn’t see coming.

For us normal folk, it could mean a frustrating waste of time and effort, missing out on the much-needed chance to blow off some steam, or perhaps a few pounds weight gain — none of which are ideal.

But for elite athletes it could have even more serious consequences, and mean missing the Olympics or Super Bowl, ending a life-long dream and costing millions of dollars in potential earnings.

Enter former Stanford professor Dr Stuart Kim, who has developed a DNA test that could predict our susceptibility to sporting injuries before we get them and allow us to alter our training accordingly to avoid or strengthen our weak spots.

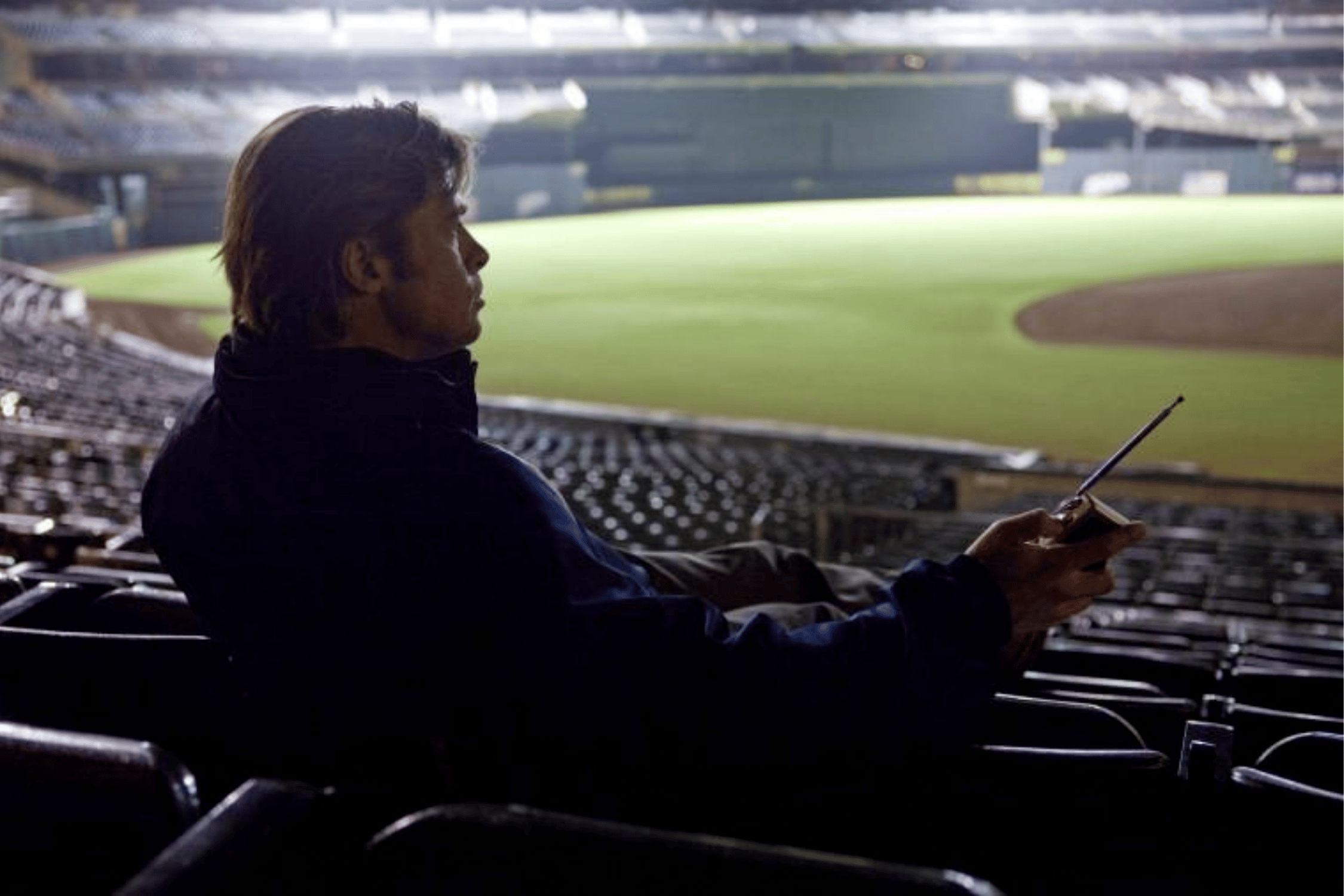

The scientific breakthrough has been compared to the Moneyball theory developed by the Oakland Athletics baseball team, who used a new approach to analyzing statistics to beat the odds and create a highly competitive team on a shoestring budget — and became the subject of an Oscar-nominated movie starring Brad Pitt.

Stuart’s company AxGen was launched in November and already counts top training centers and sports medicine companies who work with Olympic athletes among their clients. The prestigious Colorado based running club Tinman Elite, former NFL star Art Still and the 2018 winner of endurance event World’s Toughest Mudder, Kris Mendoza, are among the early supporters of the service.

And they could soon be joined by amateur fitness enthusiasts around the globe as the sports world’s answer to popular genetic testing service 23andMe.

“It definitely pertains to everybody who likes to be active,” Stuart says. “Many people who train for a marathon are not athletes, it’s more a hobby, but they’re A-type personalities. They train 20 hours a week to go to the Boston Marathon and then get hurt and can’t go — that will piss them off. How pissed off would you be if you got hurt after all that training?

“We have high-end training centers and professional teams that are using us. But there are 60 million people in the US who like to be active and it would be good for them.

“Our strategy for now is to focus on the elite as they have access to physicians and scientists who take care of them. So I just have to convince scientists that we’re legitimate — and that’s working.

“Our model is to work with top athletes to establish our brand and reputation then we can go down the pyramid. But I will eventually convince everybody that we are legitimate and this is the way to go.”

Kris Mendoza // 📸: www.toughmudder.com

By analyzing our DNA sequencing, AxGen say they can uncover genetic markers that predict our susceptibility to common injuries including stress fractures, concussion, and ankle, thumb, knee and shoulder issues. These are some of the most common injuries suffered in baseball, US football, soccer, golf, tennis, running and cycling — whether the sport is played professionally or as a hobby. And for potential clients, the service costs $210 is as easy as spitting in a tube.

Stuart says: “It’s just like 23 and Me or Ancestry. You get a kit in the mail, you spit into a tube and put it back in the mail. And that eventually turns into a DNA file and you can log into an account to see your results.”

Now for a little of the science. The genetic testing used by Stuart is part of genomics — the study of how our genes affect us. By looking at our DNA sequencing and using data and research, he has developed an algorithm for predicting what impact our DNA has on our likelihood to suffer various specific injuries.

He explains: “Anyone involved in a contact sport has to think about their risk of concussion. It’s a big deal and could end your career. We’re the only company that has the genetic marker for concussion. Just last year I did research at Stanford and found the first two strong genetic markers for concussion.

“There’s something called a polymorphism which is a place where you and I could differ in our DNA sequence. In this polymorphism, most people have an ‘a’ but some people have a ‘g’. If you have a ‘g’ in this gene, called Plexin-A4, that increases your risk for concussion by 3.6-fold.

“And we’re all about prevention. Neck strengthening exercises are good for preventing concussion. You can also wear better head gear. And we have a strength coach who devises exercises and have videos our customers can use for customized strength programming that you can add to your gym routine.

“And bone density is a big one — for me it’s the perfect storm. Low bone density is the biggest risk for stress fracture and stress fracture is endemic in endurance athletes. 50 per cent of the Stanford Cross Country team get stress fractures and it really screws up the team. But because it’s a repetitive use injury, it’s preventable. If you know you’re at risk for stress fracture you can reduce the amount of impact in your training, make sure your footwear is good, and there are all kinds of body weight exercises you can do to make your bones stronger.

“And bone density is our strongest test because in concussion there were two markers that contributed. In bone density there are 22,876. But I devised an algorithm to predict you bone density based on your DNA.

“Ankle sprain is the most common sport injury, and we found genetic markers for that. We can predict likelihood of shoulder injury, knee injury and thumb injuries that tennis players and golfers get — and here if you make sure you have good form in you swing and it will alleviate your chances of getting the injury.

“This is about predicting injuries before they happen.”

Stuart Kim

Applying genetic testing in the real world to predict specific injuries could be a big game changer for sports. It could have a huge impact on the training of sportspeople around the world, and mean fans are more likely to see the biggest stars compete in the biggest games. So could it be the next Moneyball moment for sports?

Stuart explains: “In 2000 there was a scientist that developed new technology that allowed the Oakland Athletics to evaluate players in a new way and rerank them. This guy called Scott Hatteberg did not have good statistics using the old fashioned way but using the Moneyball way he was the star. It gave the Oakland As a huge advantage and they won 20 games in a row. They don’t have a lot of money or fans and compete against the Yankees and the Red Sox because they have technology.

“This would work too. Because the team who uses this gets injured less — get a big injury before the play-offs and that’s a big deal. If you use this system your team is going to have less injuries and that’s a pretty big advantage.”

And the technology could have other benefits for both professional sportspeople and normal folk trying to maximize their performance, including helping us to better regulate our intake of legal drugs like caffeine and ibuprofen.

Stuart says: “Athletes take ibuprofen all the time because it reduces inflammation and pain. They eat ibuprofen not as a medicine but as a vitamin.

“It’s generally safe but it turns out there’s a reasonably high percentage of people who do not metabolize ibuprofen. People take it every four hours to keep the ibuprofen concentration even. But for some people their rate of tolerance for ibuprofen is ten folds lower — that’s a big deal. And these people are at danger of overdosing and you can get stomach issues and kidney issues.

“If we tell you you are ibuprofen sensitive, you get to take much less and it lasts a lot longer. The data is really quite strong and no other company has picked up on this — we figured this out first.

“And everybody drinks caffeine because it gets you going, and athletes take it because it boosts your performance and is allowed. Before their race they have caffeine, during their race they have more.

“But people differ in how fast they metabolize caffeine. Some people have a coffee in the morning and it lasts them a long time while other people metabolize it right away and they need to drink more coffee.

“Athletes should self-tune and find the optimum amount of caffeine to make them perform better. The rate in which you metabolize caffeine is highly genetically controlled. They studied athletes in Toronto on a time trial with different doses of caffeine — the fast metabolizers went 6 per cent faster and the slow metabolizers went 13 per cent slower. If you are in the Tour de France, that makes a huge difference.”

Stuart’s own journey to launch AxGen has been something of a marathon — with a few wrong turns along the way.

He set out in 2008 to find the “superhero gene” that made some athletes so physically big and strong. That was a failure, but opened the door to this venture.

“In 2008 I was studying aging and had lunch with a former NFL player and came up with the idea of doing sports genetics,” he says.

“We did a test of 100 NFL players to find out why they were big and strong. It was one of the dumbest things I’ve ever done. I was speaking to Andy Alleman who was the guard for the Kansas City Chiefs. He was the biggest, strongest guy on the field — 6ft 5in and as strong as a mountain. But his DNA was for somebody short with no power. But then we started talking about some of his risk for injuries and he became completely engaged.

“And I talked to another guy about his risk for knee injury and he said that would have been key for him deciding when to retire. He was 35 and in pain and decided on retirement, but through this test if he knew he was unlikely to get osteoarthritis in his 50s, he would have played for another year and got his biggest paycheck. So these tests that cost $150 could mean the difference between millions of dollars.”

Tinman Elite running team // 📸: Facebook/Tinman Elite

Stuart admits quitting his secure job as a Professor of Developmental Biology at Stanford to leap into the unknown was “not that sane.” But his reasons for doing so are inspiring, whatever our own personal goals.

He says: “I was a full professor at Stanford with tenure and all the security in the world.

“But I envision myself to have the spirit of an explorer. That’s what a research professor is supposed to do. To go where no scientist has gone before and do something brand new. There’s nobody doing this kind of research into the genetics of sports injuries. And it’s super easy to apply, direct to application.

“So I thought: ‘Do I start a company to try to apply this and make it widespread and useful for athletes or do I stay with my academic job?’ It doesn’t make too much sense and it’s not that sane but because I wanted to be an explorer I saw an opportunity and felt I had to do it.

“When the old time guys were sailing in their ships towards the new world, they didn’t know it was the new world. And when I think it’s going to be a new world, I don’t know that I’m not going to go sailing off the edge of a cliff.

“But there are some people that would just rather try than stay safe.”