Imagine being 17 again. Imagine it’s the days before cell phones, before the internet and all things digital dominated our existence. Imagine it’s a balmy summer’s evening, you’ve been hanging out with your friends, messing around, laughing, riding bikes. Fun was had, life feels good, and it’s time to head home for dinner.

This was the happy scene that was about to shift abruptly, cataclysmically, and forever change the destiny of a young man called Jerome Dixon. This is not a Hollywood movie, this is real life.

Jerome was a normal, joyful, rambunctious kid living in Oakland, California. Along with his twin sister, he was the youngest of a loving family of eight. Walking the short distance home after playing with his friends, one July evening in 1990, a police patrol car drew up beside him, placed him in the back seat, and drove him to a very disturbing crime scene where a young man lay dead, blood streaming from a gunshot wound to his head.

Despite Jerome’s terrified protestations of innocence, and his declaration of nearby alibis, he was taken into custody, held and questioned without any legal counsel or family member present for 25 hours. He repeatedly told his story — his truth — of where and who he’d been with that evening. But as the hours passed, the interrogating officers’ tone changed from friendly and warm to impatient and cold. Exhausted, worn down, he says he was coerced into signing a statement that admitted to the charges of first degree murder, robbery, and assault with a deadly weapon.

“They said that there were people that would put me at the crime scene, and if I didn’t tell the truth then I would never get out of that room,” Jerome recalls. “And going into the 24th hour, I just felt alone. I was terrified. I remember shaking uncontrollably with fear and uncertainty. I just couldn’t take the pressure anymore. I said, ‘Whatever you want to hear, I’ll tell you.’

“I remember tears coming down my face uncontrollably. The investigating officer slammed his hands on the table and said, ‘Finally, we’re getting somewhere — the truth.’ So the interrogating officers painted a scenario of how they believed the crime happened, and they told me to reiterate that scenario to them but put myself into the equation. And as I put myself into their equation, they began to take notes and hit the record button.”

Having admitted to the crime, Jerome went to court — still just 17 years old — and followed legal advice to take a deal which meant he would spend the next eight years in jail, rather than the 50-plus years without parole that he faced if he pleaded not guilty at a trial. But six months later, the system would burn him again; he was taken back to court, the deal was vacated, and he was resentenced as an adult. Jerome ended up spending 21-and-a-half years behind bars.

“Just imagine holding a live grenade and inside this grenade was my 18th birthday, my 21st birthday, all the milestones,” he says, describing his struggle to maintain his sanity while inside. “I missed my sisters being married, my nieces and nephews being born. Christmases, Thanksgivings, all of this was bottled up inside this live grenade. I held onto it for 21 years. And the reason I held on to it was because I knew that the moment I let this grenade go would be the moment that I would explode.”

Jerome was haunted by the admission of guilt he had signed as a teenager under extraordinary circumstances. He is not sure if he waived his Miranda rights, which give those accused of a crime the right to remain silent, and to request a lawyer. If he did, he is certain his 17-year-old self did not understand what it meant to give those rights up. It was not until after he signed his confession that he made his first phone call — to his mother.

Once in prison, Jerome avoided all cliques, gangs, and trouble — instead taking the time to look inside and work on himself. “For the most part, I entered a dark little cave,” he explains. “Mentally, I was safe inside this cave. Nobody could harm me. I had to deal with a lot of issues. I’m looking at myself in the mirror, having to ask myself the hard questions. ‘Dude, why did you confess to a crime you didn’t do?’ It was very difficult trying to come to terms with why I did what I did.”

Then at his sixth parole board meeting, against the solemn advice of his public counsel, Jerome outlined his truth of what happened with clarity and purpose. To receive parole, prisoners normally have to accept their guilt. But in a highly unusual development, he was told they believed his declaration of innocence, and he was released. He was now 38 years old.

Since that day — October 17, 2011 — Jerome has worked diligently, actively campaigning former California Governor Jerry Brown, and then current Governor Gavin Newsom, to ensure other young men and women accused of a crime are treated with fairness by authorities. He has fought for a lawyer to be present in any and all interrogating situations, and to guarantee that the detainee has absolute understanding of every word of the Miranda rights. First, he helped secure this fundamental entitlement for those 15 years old and younger in California, and has now succeeded for those 18 and younger in the state. He is currently the vice-chairman of the board of the Anti-Recidivism Coalition, and is traveling to Washington DC next month to meet with with Senator Cory Booker and Congressman Tony Cárdenas as he spearheads the charge to federalize this legislation across the country. He regularly visits prisons to inspire the inmates. Meanwhile, his legal team is filing an application for a pardon of innocence with the Governor’s office. Now 50, his overall intention is to feel “whole” again.

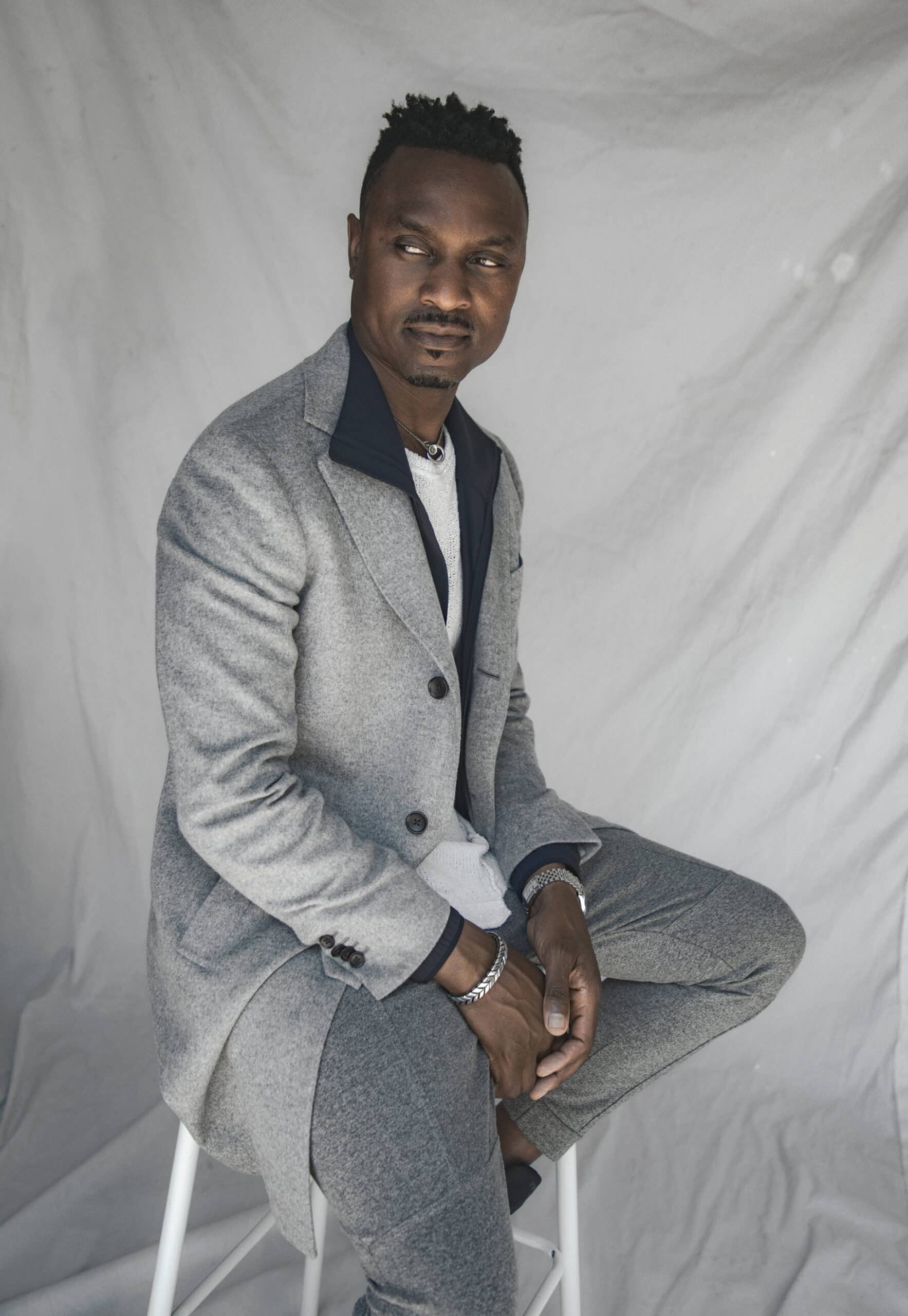

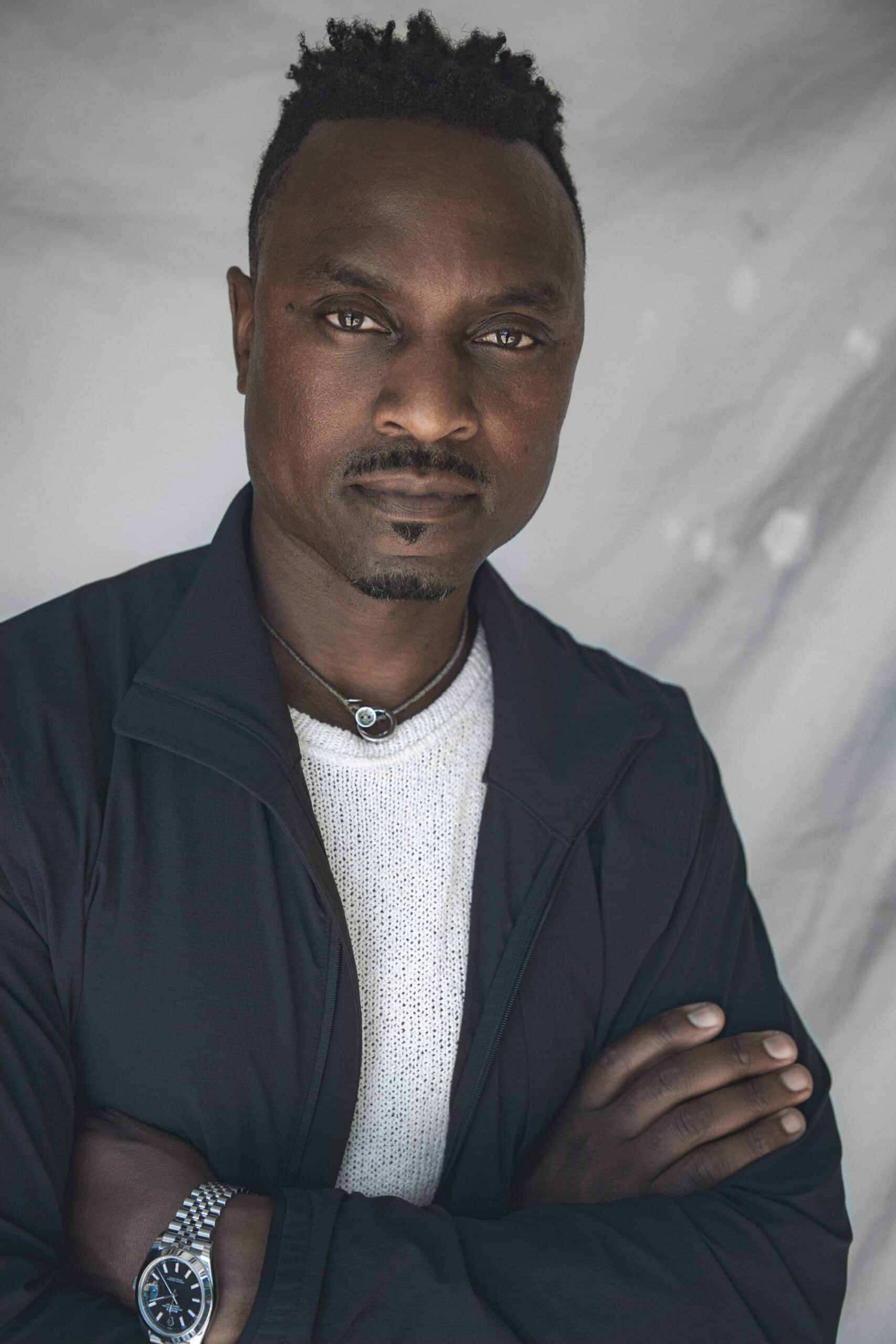

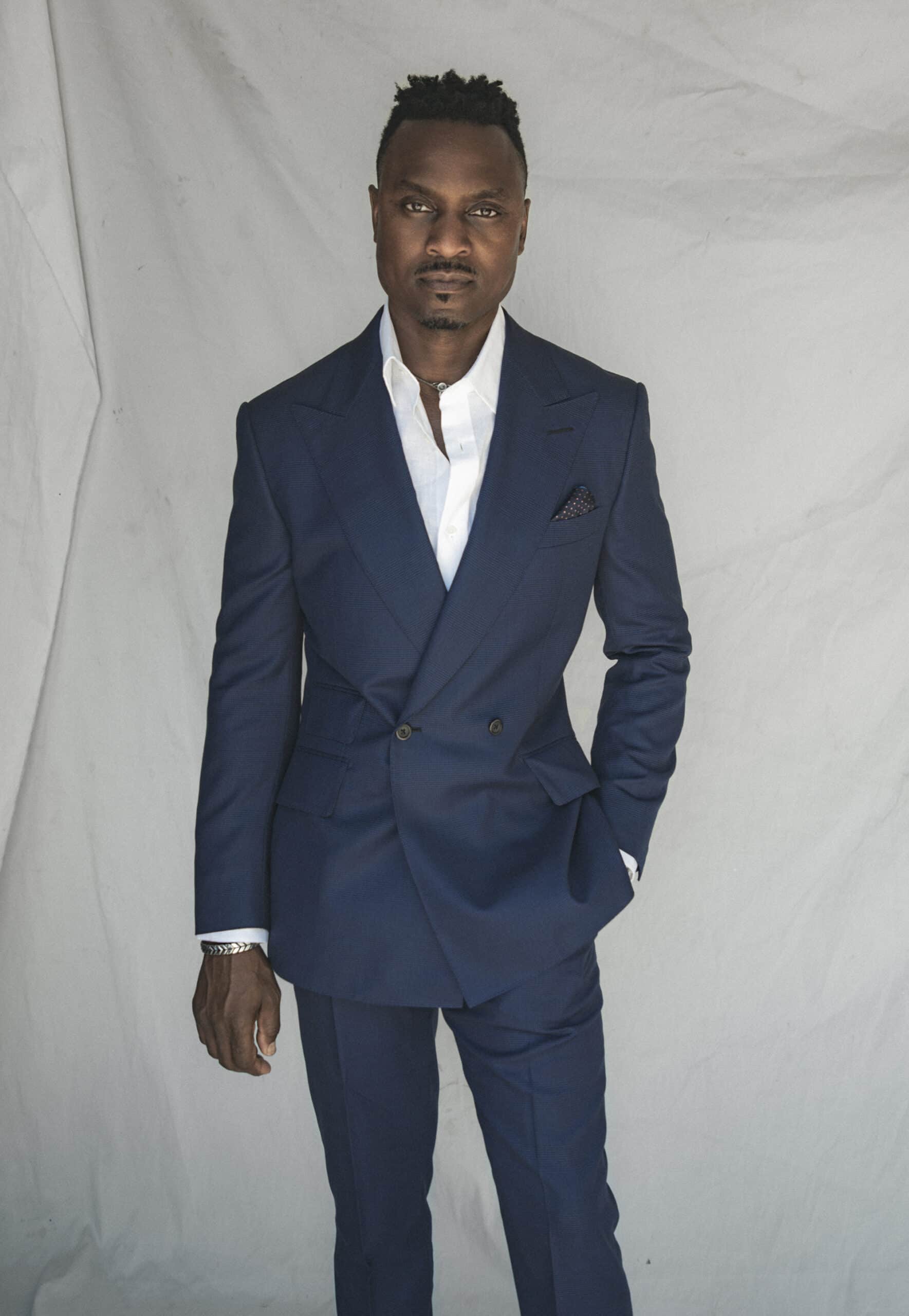

There is a somewhat lighter sidebar to this weighty and important story. While in prison, Jerome found hope and solace in studying the pages of GQ magazine every month. “When I was locked up I developed this fascination for style,” he explains. “So I would always go to the prison library, pick up GQ magazine, thumb through the pages and be like, ‘One day I want to dress like these guys.’ It was my vision board, something to aim for. That was my fixation — getting to that little speck at the end of my tunnel.”

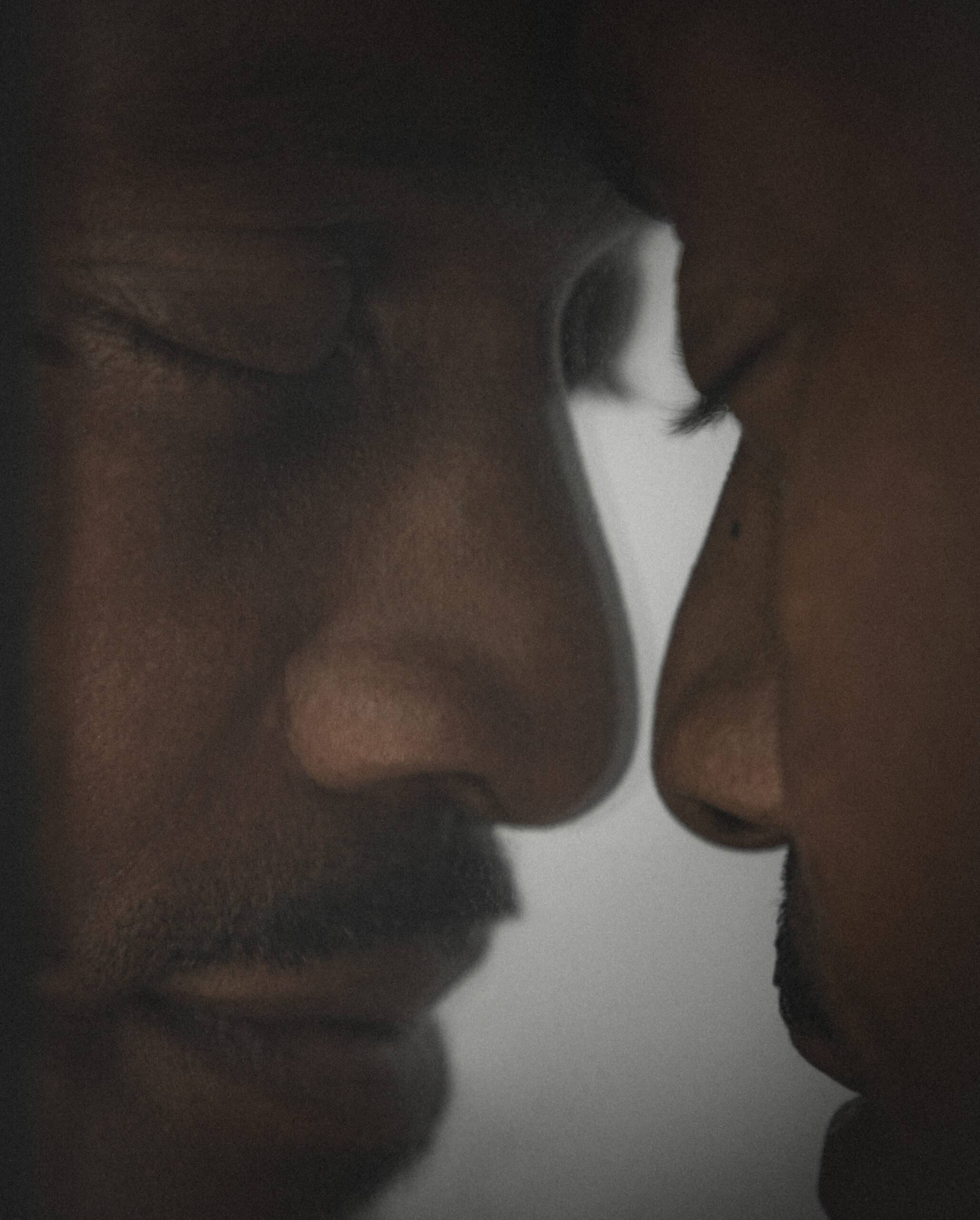

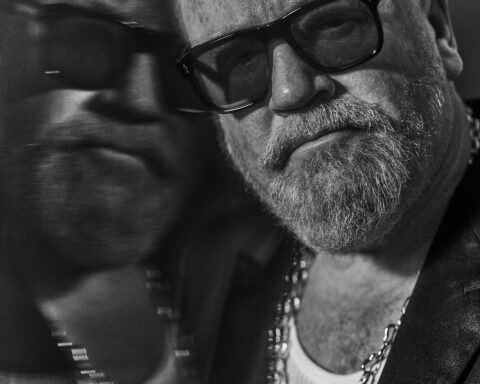

So I was honored to help style Jerome for our Mr Feelgood cover shoot, a creative partnership made particularly pertinent by the fact that I featured as a model in many of the GQ magazines that helped him maintain hope in prison. “For over a decade Jerome stared at your images,” his wife, Raha Dixon, tells me. The couple met at a talk on racism and social change in Santa Monica, California, in 2019, and married two years later. “And as a coping mechanism, as a means to stay sane and alive, he said, ‘One day I will look like that man, I will dress like that man, I will be that man.’ Now, years later, I watched that same man coach Jerome, and put his clothing on him, and show him how to act and pose for a photoshoot. I think the GQ story is not just about Jerome, it’s about you and Jerome and the power of manifestation. You kept him going for so long, then when he comes home you discover him and give him this platform. It’s so wild to me to see this come full circle.”

Here at Mr Feelgood, my joy is that I get to celebrate men from a broad variety of backgrounds. Some are leaders in their fields. Some are famous. Some go quietly about their business, for the most part uncelebrated, and rarely get a public platform to share their life’s work. Once Jerome was finally released, he did not waste his new chapter on bitterness or animosity, but decided to use his experience to help others. His story is one of fear, injustice, anger, frustration, and deep sadness. But it is also one of patience, self-control, hope, character, endurance, and the presence of grace.

So how does he remain so positive amid such injustice? “It’s just like any exercise,” says Jerome. “If you want to work on a certain muscle, you have to be consistent with it — and a lot of it had to do with my personal growth. I had to work on my self. When I came home I didn’t want to be that angry Black man that just came out of the system. Nobody wants to be around someone that’s angry. It’s reflected in that grenade picture that I painted. When they said to me, “Mr Dixon, get out, go home,” I had to choose to leave that grenade at the prison door.”

While Jerome is yet to be fully exonerated, parole board members, legal experts, leading politicians, and social justice campaigners all now believe and accept his version of events. And — having met Jerome earlier this year, before getting to know him over the coming months — I do too. To hear his story for yourself, please watch our video interview, here and on our Mr Feelgood TV channel, and read a transcript of our conversation below.

Mr Feelgood was created as a platform to share stories that add to the understanding of this crazy thing called life. When we met previously, you struck me so deeply as a man of integrity, given what you endured — being arrested at 17 years old and incarcerated for 21-and-a-half years before you were exonerated. I was blown away by your grace, empathy and wisdom, and I would love to share your story.

Thank you, but one correction. I haven’t been exonerated yet. But I’m in the process of being made whole.

July 25, 1990. Wrong place, wrong time. A murder occurred and I was about two-and-a-half blocks away. The police picked me up, drove me to the crime scene and when we arrived, there was a group of officers there, surrounding a body that was laying on the pavement. From the back seat of the patrol car, I could see a river of blood running from this body. The young man was shot in the head, and moments later a sergeant came up to the side of the patrol car, opened the door and the first words he uttered to me were, “Young man, you have a lot of explaining to do about that dead body.” I don’t remember what my exact words were in response, but I said something along these terms, “I don’t know what you are talking about. I was up the street with my friends, who are still there.” His response was, “If that’s the game you want to play, so be it.” He slammed the car door.

I remained in the back seat of the car for a long time. At this point, I was not handcuffed. I could also see from a distance that there were three individuals who were surrounded by law enforcement officers. The officers shone a bright light on my face and walked these three individuals over to the car. I could hear the individuals crying, and I could also hear one of the individuals say, “Yes, that was him.”

They took me downtown. There, I was put in a room, and in the room was a table and chairs. An officer came in with a clipboard and some paper and said, “I just want to have a conversation with you. Why don’t you tell me what happened?”

I told him what happened. I told him that I was at my friend’s place and we were hanging out all day there. I was waiting for a friend of mine to come pick me up and take me home. Some time later, the officer walked out of the room and then there was another officer that came in and asked me the same question. I repeated the same truth statement. This went on for hours and hours. In fact, it went on for 25 hours.

Didn’t you get a phone call? Are they allowed to hold you for that amount of time?

I wish I had the legal jargon to answer that question. I don’t. They read me my rights in the 25th hour. For the first eight hours the interrogating officers were extremely friendly. They were very engaging. Going into the 16th hour, their demeanor and tone changed dramatically. It became more authoritative. The tone was, “You’re lying. You’re not telling the truth.” They said that there were people that would put me at the crime scene and if I didn’t tell the truth, then I would never get out of that room. And going into the 24th hour, I just felt alone. I was terrified. I remember shaking uncontrollably with fear and uncertainty. Coming up to that 25th hour, I just couldn’t take the pressure anymore. I said, “Whatever you want to hear, I’ll tell you.” I remember tears coming down my face uncontrollably. The investigating officer slammed his hands on the table and said, “Finally, we’re getting somewhere — the truth.” So the interrogating officers painted a scenario of how they believed the crime happened, and they told me to reiterate that scenario to them but put myself into the equation. And as I put myself into their equation, they began to take notes and hit the record button. This is how they got a confession from me.

My confession alone was used against me. I was presented with, as my public defender said, a guaranteed deal. She said that I was in a no-win situation, and it would be in my best interest to take this special deal to the California Youth Authority (CYA) for first degree murder, three counts of robbery, and assault with a deadly weapon. She said that by pleading to this, I would be released before my 25th birthday and I would have my whole adult life ahead of me. I didn’t know what else to do. I kept saying, “I didn’t do it, I didn’t do it.” It didn’t matter. I was in a no-win situation. And so I took the deal.

Six months into that committed deal, I was brought back to court. That deal was vacated. I was now tried as an adult and I was presented with a new deal, which was, plea to a lesser charge, from a first degree to a second degree, and by doing so I would be pleading to a sentence of 18 years to life in adult prison. Once again, I was in a no-win situation. I had already confessed and I had already pleaded guilty. And so, again, I didn’t know what else to do. Now 18, if I didn’t choose that second deal, I would go to trial. And my public defender stated to me, based on my confession, I would lose and would receive the maximum sentence of 50 years to life in prison. So I chose 18 years to life, second degree murder, and was sent back to the CYA and remained there until I was 23. I was then transferred from the CYA to the adult Department of Corrections and Rehabilitations, which is prison. Now I have to deal with a parole board process for them to determine whether or not I would ever be eligible for parole. However, I was an indeterminate ‘lifer’, and so that meant they could hold me in prison for life.

I appeared before the parole board five times, and each time I appeared before them, my stance was: I don’t want to talk about the life crime, because they didn’t want to hear it, and I wouldn’t be shown any type of due justice. So the district attorney stated, “If you’re not gonna talk about your life crime, you’re never gonna get out of here.” And so at my fifth hearing, I decided to explain how a 17-year-old kid — who at this time was a 35-year-old man — was put in an adult situation, and was now fighting for his freedom. I tried to explain it to them the best I could, but I just didn’t come across with clarifying answers, and so I received a three-year denial. That puts me now at the 21st year [in prison]. So I appeared again, and this time I explained, with extreme detail, how I was put in an adult situation for 25 hours, forced to confess to a crime I didn’t do. I was now a 38-year-old man.

While in prison I did not have one rule violation, and so that was a huge question for the parole board. How was it that I had spent 21 years in prison and didn’t have any rule violations that would show that I needed any type of rehabilitation? I had an answer for them. I told the commissioning panel that I didn’t belong here, and therefore I wasn’t going to act like I belonged here.

The parole board went to recess and upon their return, they acknowledged my innocence. That was something that the parole board has never done before, acknowledged an individual’s innocence.

They went as far as saying, “Mr Dixon, we’re not absolving you from the injustice that occurred some years ago, we’re saying that you don’t belong here, so we’re going to find you suitable and release you.” So I was paroled to the Los Angeles area on October 17, 2011. Upon my release I had a job offer at a law firm. And so on my second day home, I walked into the law firm and had a position as an intern, and I stayed there. I tried to adjust as best I could. The only people in the law firm that knew about my past were the senior attorney and his partner. So I masked where I came from very well — because I didn’t want to be judged again and again. Because I wasn’t exonerated, there would always be that question mark. You say one thing, but the courts deem something else. So that was always a struggle for me.

How did you deal, as a young man of 17, being taken away from a loving family and being put into a youth prison? How did you deal with the terror and the fear, the loneliness and the unjustness of this situation? How were you able to protect yourself, keep your marbles, and keep your faith?

Number one, it was very difficult. I never cliqued up in prison. I never cliqued up with any prison gangs. The last thing I wanted to do was call home and say, “Hey mom, guess what, I’m a gang member now.” It was bad enough that I was in prison for something that I didn’t do. So I was an outsider. I was ostracized because I didn’t clique up. And there was a lot of backlash from being an outsider. I was ostracized and it was very difficult. While everybody was working out, I would just take to the track and run. I’d run for like four hours out of the day. I found peace in doing it, running around the track. So much so that when I came home, I decided to run marathons and I’ve ran eight marathons since.

And for a period of time in my incarceration, I didn’t really speak much. There were only two words that I uttered, and that was, “What’s up?”

You asked how I maintained my sanity for all those years. For the most part, I entered a dark little cave. I was safe there. Mentally, I was safe inside this cave. Nobody could harm me. I wouldn’t allow anybody in. I had to deal with a lot of self issues. I’m looking at myself in the mirror, having to ask myself the hard questions. “Dude, why did you confess to a crime you didn’t do?” It was very difficult trying to come to terms with why I did what I did.

I was 17. And those first 17 years of my life were joyous. I was the typical, rebellious, rambunctious child growing up. Just like any other 17-year-old. I have questioned myself a great deal. What did I do in those 17 years that made me deserve this? And I just couldn’t come up with any logical answers that would justify me being sent to prison for a murder I didn’t do.

I missed out on a lot of positive lived experiences for 21-and-a-half years. Just imagine holding a live grenade and inside this grenade was my 18th birthday, my 21st birthday, all the milestones. I have a big family. There are eight of us in all. I’m the baby. I have a twin sister. I missed my sisters being married, my nieces and nephews being born. Christmases, Thanksgivings, all of this was bottled up inside this live grenade. I held onto it for 21 years. And the reason I held on to it was because I knew that the moment I let this grenade go would be the moment that I would explode.

I also had to do a lot of self-reflection. I had to do a lot of looking in the mirror. Going back to that 17-year-old kid, and asking, “Why did you do it?” Let’s get to the root cause of it. I remember there was a time when my parents had decided to separate, and they called all of my siblings into the living room, and told us that they would be separating. I was a child, maybe 10 or 11. I remember I was devastated hearing those words from our parents, and I ran into my room and my older sister came in behind me. I was laying on the bed crying and she was trying to console me. I remember telling her what she wanted to hear to get her to stop talking to me. And during that time I developed that learned behavior, so anytime I got into a pressured situation, conflict, I would tell people what they wanted to hear to get out of that situation. So, as a 17-year-old kid, put in that adult situation, what happened? I told law enforcement what they wanted to hear, thinking that would save me, but it didn’t.

How was the transfer from a youth to an adult prison? Did you have a cellmate?

I had multiple cellmates. It was difficult, because you’re celled up with somebody who you know nothing about. I learned a lot of things from a lot of individuals in prison. Some good things and some bad things. There are some good people in prison and some bad people in prison. Like there are good people in the world and there are bad people in the world. There are bad cops out there and there are good cops out there. I chose to take those lessons and incorporate them into my lifestyle. And as a result of me taking those lessons, this is the person who you are speaking to today.

But let me just say this, in 21 years [in prison] I’ve never seen anyone raped. I’ve never seen anyone abused. Are there stabbings ? Are there riots? Is there gang violence? Yes, absolutely. In retrospect, I was very fortunate to miss a lot of that.

I can’t believe that you say you’re fortunate. This is one of the reasons I wanted to provide a platform for you on Mr Feelgood. You have such grace, and such lack of animosity and bitterness, for having 21-and-half integral years taken from you. How did you do that? Did you make a conscious decision not to be angry?

Great question. You know, it’s just like any exercise. If you want to work on a certain muscle, you have to be consistent with it — and a lot of it had to do with my personal growth. I had to work on my self. When I came home I didn’t want to be that angry Black man that just came out of the system. Nobody wants to be around someone that’s angry. I’m sure that you have people in your life that just release this negative aura, and you don’t want to be around them — I just didn’t want to be that person. And a lot of that is reflected in that grenade picture that I painted. When they said to me, “Mr Dixon, get out, go home,” I had to choose to leave that grenade at the prison door. I was holding onto a live grenade for 21 years and that live grenade represented my sanity.

My mother didn’t visit me for 21 years because she was under the impression that if her child is innocent of the crime, her child should be coming home with her if she goes to see him. But that was a reality that my mother knew was not true, so she just couldn’t muster up the courage to come and visit me. I didn’t understand that for 21 years, but when I came home and we had a long conversation, she explained that to me and I now understand. She believed wholeheartedly that I was innocent, but the justice system was unfair and she knew that they wouldn’t give me justice — so she just couldn’t muster up the courage to come and see me.

But she and I developed a strong bond corresponding. I would get a blank piece of paper and I would outline my hand print. I would take that piece of paper and I would hold it to my chest and I would hug it, and then I would put it in an envelope and I would send it to her. The reason for doing that was so my mom could see how I was growing, and that became our love language over time.

You mentioned that while you were inside you worked in a hospice, can you tell us a little about that?

Being a hospice care provider definitely changed my perspective on life. I was assigned to individuals that became terminal. You develop relationships with these guys. And they have heartfelt conversations, not about their crime but just about life in general. Then you watch them come to their end of life. I would sit at their bedside and would watch them breathe their last breath. There would be a calming peace in the room. They would lock you in the room, so after the individual would take his last breath I would just take a minute to take it in before pushing the button to summon the medical staff and the correctional officer. It would be an out-of-body experience. As soon as they come in, they send you on your way and you go back to the yard. Then there’s medical staff that you talk to about the experience. You have to. You can’t keep that stuff in, you’d go crazy. So again, those lessons that I learned in there, I incorporated into my own life.

Did you have a mentor, a chaplain, someone that you could speak to, especially when you were young? Someone that you give counsel to help you adjust and cope?

When I first got locked up I was battling with myself, trying to understand how I got in here, and my belief in God was shattered. I began to wage a war with God. Why would you do this to me? And so I shied away from religion. I didn’t want to be associated at all with religion because I believed at that time that God abandoned me. What kind of a God would put a child through a situation like that?

You asked about mentors. I looked to the prison yard and that was my rite of passage, my coming of age. I had to grow up really quickly and so I learned from a lot of the men in there. On how to be, on how to conduct myself — both positive and negative. So, they were all my mentors, believe it or not — I had to grow up in prison.

What about crying? What about showing weakness? Did you cry?

I remember I cried at the beginning, when I was being interrogated for those 25 hours. And towards the 20th year, there was an outburst of tears that overwhelmed me. That was when my sisters came to visit me to tell me that my Dad had passed away. I’ll never forget that day. I received about four visits a year [from my sisters] and each visit would last about three hours. They were in Northern California and I was in Southern California, so they would drive six hours just to come visit me, spend three hours, and then they’d be back on the road. So 12 hours a year is how much I saw my family.

Every time my sisters came to visit me, I would present the aura that I was in control, this place is not breaking me. So when they saw me, they saw this strong young man, doing his best to try to overcome this dire situation which he was in. But this particular visit was different. Their body language was different. I came into the visiting room and I sat down and it was dead silent for a moment, and my sister Gwen said, “Your dad passed away.”

I always wanted my dad to see me walk out of that place, strong and victorious. And he never got that opportunity.

I didn’t break down in front of them because I didn’t want them to see that vulnerability. The tears didn’t come until the next day. I will never forget it, the next day I went to my prison job assignment and there was another inmate in there. It all came out in front of him. I was sitting at my workstation and was crying uncontrollably. He came and stood behind me, tapped on my shoulder and just said, “I understand.” I got myself together, he walked out and that was all we ever said.

It was a defining moment for me. I became stronger. I think it allowed me to have a stronger voice when I went to the parole board to speak for that 17-year-old kid. People were telling me that I shouldn’t go to the parole board and tell them the truth because I would do more harm than good.

Was your counsel that day privy and supportive to the truth you were taking to the parole board?

My prison attorney advised me not to do that. When the commissioning panel ruled in my favor, we walked out and he was like, “We did it,” and wanted to high-five. I was like, “‘We’ didn’t do anything, you were advising me to do the opposite.” And if I had done the opposite, I would probably still be in prison today.

So what are you doing now? I know you’ve been in Washington DC, tell us a little about the legislation you are campaigning for?

In 2017, I was asked by Human Rights Watch and another organization, the The Anti-Recidivism Coalition, if I wanted to help spearhead the charge for the juvenile Miranda rights bill. And I jumped on it. So we went to the state capital and I testified before lawmakers about the importance of having juvenile Miranda rights applied, so that any time a child is in a custodial situation and being interrogated, an attorney will be present and explain line by line what their rights are. That was something that did not happen for me. I was elated to be a part of this process and [former California Governor] Jerry Brown signed off on that bill protecting children 15 years and under. Fast-forward, we thought that 15 was not the appropriate age, and the age should be 18. So I spearheaded the charge and Governor Gavin Newsom wound up signing off on that bill. So now, children in the State of California are protected under the Miranda rights rule until 18. It’s not excusing them, we’re not giving them a get out of jail pass, we’re saying that every time a child is in a situation where Miranda is applied, their rights will be explained completely and fully. Now we are on a national push to get the juvenile Miranda bill federalized so that it applies in every single state. Look, what happened to me doesn’t mean that I’m a unicorn. This has been going on for years. I’m not the first. I’m one of many that has confessed to a crime that they didn’t commit.

Tell me about receiving GQ magazine every month when you were in prison?

When I was locked up I developed this fascination for style, so I would always go to the prison library and pick up GQ magazine and thumb through the pages and be like, “One day I wanna dress like these guys.” It was my fantasy, that’s what I dreamt about. It was like a vision board, something to aim for. That was my fixation — getting to that little speck at the end of my tunnel.

Where are you now Jerome? And where do you want to be?

I’ve been happily married for two years now to a lovely woman. I love her. That was the best thing that I could’ve done. My whole perspective has changed. We’ve bought a new home. We’re truly blessed with that as well.

I’m really fixated on this juvenile Miranda rights push — to get it federalized across the board because I don’t want what happened to me to happen ever again. We know that it will happen, but I could at least put up roadblocks to prevent it — and that is the passage of the juvenile Miranda rights.

And I know how involved you are with your stepson…

I don’t call him my stepson. I put him to bed every night. I get him up in the morning. Take him to school. I go to all of his school functions. I’m his dad. If you did a checklist. I would check every single box. I’ve even got the socks that say I’m the “Number One Dad.”

Learn more about the Anti-Recidivism Coalition

Oh my word. What a devastating story… yet, this amazing man has such character! I’m so very happy for his release and the chance to live a life of liberty and freedom now. The whole GQ connection and getting to talk with you, John, is absolutely incredible. I don’t think I’ll ever be the same, this true story is obviously deeply moving and I’m grateful to have read it. Thank you (both) for sharing. P.S. What STYLE he has! Incredible photos!