We’re used to archetypical hero figures in novels, TV and cinema, but walking among us are a network of individuals who fought against very tall odds, working night and day, contributing to the foundations that support a vibrant and evolving society.

From 1948 and until 1971, the British government called on the services of the Commonwealth countries, inviting their residents to come to Britain to help rebuild the country after the devastation of the Second World War. These jobs included the production of steel, coal, iron, and food, as well as roles in running public transport and staffing the National Health Service.

Answering that call, thousands arrived from the Caribbean countries, and the movement became known as the Windrush generation, the name given after HMT Empire Windrush docked on June 21, 1948 at Tilbury Docks in Essex, and its 1027 passengers began disembarking the following day. These people faced terrible racism and challenges that would test their nerve and dignity, but they persevered and not only gave their energy and skill sets but also contributed all aspects of their culture which to this day thrives and has improved the cosmopolitan hues of modern Britain.

As part of the 75th anniversary of this vital part of British history, photographer and director Steve Reeves has been capturing portraits of the remaining elders of this significant generation and documenting their personal stories. With huge appreciation, we invite you to enjoy Steve’s work as we glean wisdom and knowledge from the lives of these remarkable men and women and their legacy of contribution.

Henry

Henry was born in Snell Hall village in St Vincent, Grenada. The village was named after slave owner William Snell (1720-1779).

On June 15th, 1961, Henry took the boat to England. His mum was so upset that her boy was leaving that she couldn’t bare to look when he got on the bus to take him to the port.

Just a few days after arriving, Henry was working as a carpenter for Wandsworth Council. He’d also found somewhere to live in Shepherd’s Bush, so he sent for his wife, Marge, to come over from back home in Grenada.

One of Henry’s first jobs was doing the ‘shuttering’ for the Winstanley Estate in Battersea, which was under construction at the time. Henry’s job was to build wooden moulds that concrete was poured into to create the walls of the tower blocks.

Henry and Marge had four children together. When she was in her 40s, Marge visited her sister in America. After returning, she was at the market when she had a stroke and died. Henry told me that Marge had always suffered from headaches. “My wife was so good that she died early. It’s only the good that die young.”

Henry is 94 now, and his eldest child is a pensioner. He walks without a stick and always sits on the top floor of the bus. He said, “When people get to my age, they get aches and pains but lucky for me, I don’t have any.”

Henry doesn’t take any medication and never visits the doctor. “I’m happy in my own way, and I don’t worry about nothing. The trouble with people is they all want to be rich. All you should want in life is to see the daybreak — that’s all you need.”

“I had my little job, I worked for Wandsworth Council until I retired, I still get my pension money from the government, what’s better than that?”

“Every day, I’m up at 6am. I get a cup of tea and get out of the house. All I want is to keep going.”

Henry told me he was in Clapham because he’d been doing a carpentry job. He always keeps his leather holdall in a Sainsbury’s bag. “Because if people see you with a leather briefcase, they will want to steal it.”

He told me that even though Marge died 47 years ago, he still has conversations with her in his sleep. Last week, she said, “Have you made up your arrangements for your funeral yet.” Henry told me that he replied, “I ain’t going nowhere.”

“I was born in the gutter, and I lay in the gutter smiling, waiting for the water to take me to the big sea.”

Monica

Monica often gets the bus to Trafalgar Square to sit on her favourite bench. She loves the square because there is always something going on. It also gives her a chance to do her scratch cards.

Monica is 77 and was born in St Lucia. In 1960 when she was 18, she came to the UK on the ship ‘Bianca C.’ Monica was seasick for most of the 3-week voyage. It could have been worse, because a year later, the ship sank off the coast of Grenada.

Life wasn’t easy when she first arrived in the UK. She saw the signs in the windows, “No blacks, no Irish and no dogs” and the chilblains were horrible.

She got a civil service job and, eventually, became the Prime Minister’s messenger in Number 10 Downing Street.

She worked for Tory PM, John Major and Labour PM, Tony Blair. She said they were always nice to her, “Because I was always nice to them.”

Tony Blair introduced her to Mandela. She remembers waiting in the hallway, and before she even saw him, she immediately recognised ‘Papa Mandelas’ voice. He signed her book for her.

There was a lunch at Number 10 to celebrate ex-PM Ted Heaths’ 80th birthday. Mr. Major asked Monica if she would like to meet ‘Her Majesty,’ and Monica was introduced to The Queen.

Monica told me that the Queen was softly spoken and asked, ‘How long have you been here?’ Monica wasn’t sure if she meant how long you have been in the job or how long you have been in the UK. She can’t remember her answer because she was so nervous — she just curtseyed as the Queen replied, “I hope you enjoy your stay.”

She said the rudest visitor was Vladimir Putin. He walked past her. He said, ‘Goodbye,’ but didn’t look at her once.

Monica met many famous people like Shirley Bassey and Cliff Richard, and she enjoyed the parties on the lawn at the back of Number 10. She said there was no Covid then, so the parties were no problem.

Monica has two sons and five grandkids and owns her house in East Ham.

When she was at school back in St Lucia. The girls hoping to come to the UK had to write down what they wanted to achieve when they got here. Monica wrote that she would love to meet the Queen. The teacher laughed and said, ‘You never will.’

Arnold Ebenezer Tomlinson

Arnold Ebenezer Tomlinson was born in the parish of Westmoreland, Jamaica in 1923. He grew up on a farm with his sevem brothers and sisters. His dad grew sugar cane and kept donkeys, Arnold would help on the farm after school.

He came to England in 1956. He remembers being shocked at how cold it was on the dock as he disembarked at Southampton. He got lodgings in Battersea and a job working at a nearby factory. Once he got settled, he sent for his wife. Arnold did many jobs back then, including working in the canteen at London Airport (now Heathrow). He used to peel the potatoes and mash them up. However, he spent most of his working life as a painter and decorator for Southwark Council.

When he wasn’t working, Arnold enjoyed going to house parties. He never really went to the pubs because he wasn’t much of a drinker. “I’m not a pub man. I liked to go dancing.”

The couple had a son and saved enough to buy a house in Stockwell. Arnold was the first Tomlinson to come from Jamaica to England. He led the way for other family members. He took in his nephew, who came to England after his father died. He also helped his two brothers get established in London. Arnold has outlived them all.

Arnold and his wife divorced in 1979. In 2000, a friend introduced him to his new wife, Mervelee. They married at the Peckham Registry office and now live in Bermondsey.

Arnold always loved gardening. He’d make the front garden look pretty with flowers and grow vegetables at the back. It’s too much for him now, so Mervelee has taken over the task. He also loves a flutter on the horses. He used to go to the bookies himself, but now when there’s a big race or fight, Mervelee places the bets for him. Every day, Arnold makes breakfast. He does toast and tea and boils eggs. He no longer eats the eggs himself but cooks them for Mervelee.

Despite being 100 in just a few weeks, Arnold has perfect vision. He doesn’t even need reading glasses to read his daily paper which he reads from cover to cover while drinking Baldwins Sarsaparilla (a soft drink).

Looking back at his 65 years of living in England. Arnold thinks the country has treated him ‘good and bad.’ But when he weighs it all up, he feels that the good outweighs the bad.

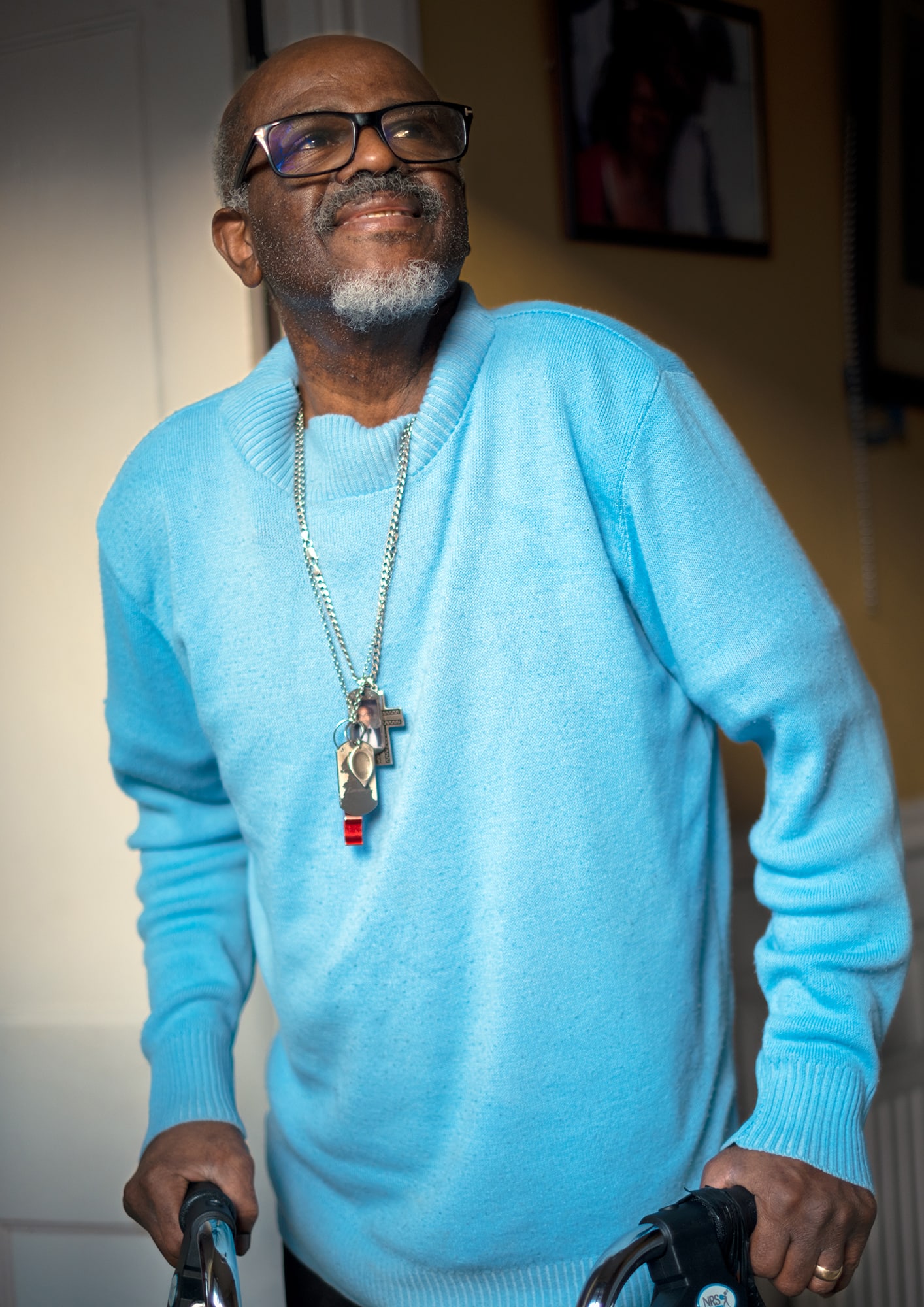

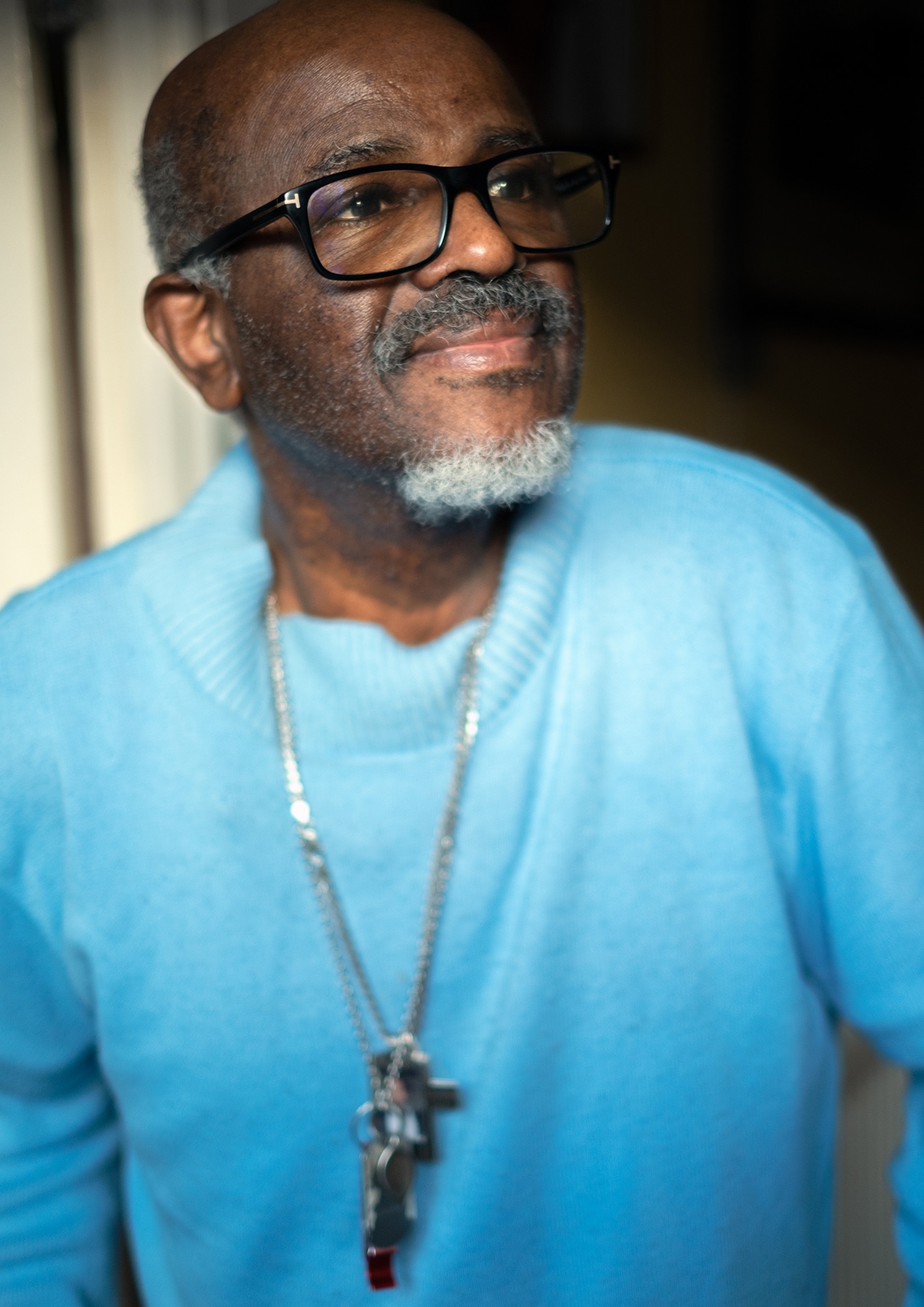

Phillip

Phillip is originally from British Dominica and was a trained carpenter. He told me, “I can take a piece of a tree and turn it into a cabinet.”

When he was young, many of his friends left British Dominica for America as soon as possible. Phillip stayed because his work was “going good” and he had “plenty girlfriends.” However, when he was 24, he got one of them pregnant. As soon as he discovered this, he found his passport and got on the first boat to England.

Phillip sent money back home to help pay for his daughter’s upbringing but stopped when he found out that the money was being spent on other things, and he lost all contact with her.

In the ’70s he was playing darts in a local pub when a woman turned up and started talking about his past. Phillip didn’t understand how this woman knew so much about his life until she told him that she was his daughter. Phillip told me, “It was lucky I had strong legs because I nearly fainted when I realised who it was – she looked like my sister.”

Phillip’s daughter lived in America and had come to the UK to search for Phillip. She had a rough idea of where he lived and had heard that he was into darts, so was going into different South London pubs hoping to find him. Eventually, she hit the bulls-eye and found her dad. After this meeting, they saw each other every day until she returned to America, where she still lives as a retired accountant. Despite the distance between them, Phillip and his daughter have remained close, and she calls him every Sunday to check that he’s okay.

Phillip no longer plays darts as he damaged his shoulder when he was the victim of a racist attack in Brixton in the ’80s. Phillip told me that it was lucky there was thick snow on the ground as it cushioned his skull as the attacker repeatedly banged it against the pavement. Phillip was saved by a passer-by, a guy from Malta who dragged the man off of him. A few years ago, Phillip bumped into the Maltese guy and got the chance to thank him for saving his life.

I took this shot on the first day of Lockdown Two. Phillip said he’s refusing to stay indoors as he did during the first lockdown as his body “locked up” from lack of activity. This time the 91-year old told me that he will continue his daily routine of Walking on Clapham Common no matter what.

Stella

Stella has a great sense of humour. As I attempted to take her photo, she said, “Take your time and hurry up.” She then told me in a whisper, “I’m 89 but don’t tell anybody.”

Stella came to England from Guyana in 1955. She enjoyed the journey across the Atlantic. It took two weeks, and every night, they would show movies in the lounge. On board the ship were families, single men and women and many children. Everyone was excited about starting a new life in England.

Her husband, Cecil, had already come to England. He was working as a carpenter and living in Tooting. Stella left their son with his parents until she got settled.

Stella wasn’t sure about England at first but it was her sense of humour that helped get her through those early years. A white woman once looked at her hands and said, “Oh, look at that, you wear a wedding ring just like us”. Stella replied, “We normally wear our rings through our noses but put them on our fingers before we get off the banana boat.”

Stella and Cecil lived in a single room in Tooting. Cecil worked, and Stella trained to become a nurse. The couple also had a baby daughter called Wendy.

Stella then sent for her son, but her in-laws had grown attached to him and wouldn’t let him come. Stella joked that although many English people think that people in the Caribbean lived in mud huts, her in-laws had a big house with six bedrooms. They argued that there was no way that they were going to send their grandson to live in a single room in South London. So Stella’s son remained in Guyana with his grandparents and still lives there.

Once Stella passed her nursing exams, she worked in the infectious disease ward at St Georges Hospital in Tooting.

She said that the hospital had a strict hygiene policy. You’d scrub your hands, go into the ward, put on overalls, and then scrub your hands again. There were no disposable surgical gloves in those days. She said you had to go through the same process on the way out. She said that all the hand scrubbing made her hands sore.

The nurses were given castor oil cream to soothe their hands, but it had a strong smell that Stella was self-conscious about on the bus ride home. The whole time Stella was a nurse, there was never any cross-infection.

Stella’s daughter Wendy became a teacher. When she was in her early fifties, she started to get stomach pains. Because she was so dedicated to her work, she wouldn’t visit a doctor until the school holidays. When she finally went, it turned out that she had advanced liver cancer, and sadly, she passed away shortly after.

Wendy had five children who often visit Stella. Stella feels blessed that she has all her grandkids around her. She says when they leave the house after a visit, ‘The silence is deafening.’

Cecil passed away in 2009. He loved gardening. He’d grow vegetables in the back garden and flowers in the front. Stella told me everyone was friendly on the road where she lived in Tooting. Back then, people were always popping in and out of each other’s houses. Everyone grew vegetables and cared for their gardens. The neighbours would share plants and seeds.

During this time, Cecil planted two beautiful roses in the front garden. Now that she lives alone, Stella got the garden paved because it was too much for her to look after. She ensured that the builders left Cecil’s roses untouched. Every summer, without fail, they always burst into bloom.

Veronica

Veronica came to England from Jamaica when she was nine. Her mum was just 25 and had given birth to Veronica when she was a teenager and still at school.

Everyone knew Veronica’s mum as Pearl, and she was a talented seamstress. Veronica’s dad, Charlie, worked for British Rail. He was also a skilled carpenter and picture framer and could make and repair shoes as a hobby. They settled in Clapham in south west London.

For newly arrived West Indian families, inherent racism from the banks and the fact that they had no history in England meant that getting a bank account was very difficult. Because of this, many people from the Caribbean set up ‘Pardner’ Schemes.

The Pardner system was initially brought to Jamaica by enslaved Africans and used to purchase freedom.

The scheme is based around a group of friends, neighbours or relatives agreeing to contribute money into the pot each week over a fixed term. Each month, a member of the scheme gets the whole pot which means they get a lump sum to help pay for a deposit on a flat, set up a business or get a car or similar. This scheme is based entirely on trust, and only people with a good reputation are allowed to participate.

Veronica’s family used the Pardner scheme a lot in those early days in the UK.

When Veronica was small back in Jamaica, she fell from a verandah and injured her head. Her family didn’t think her injury looked that bad and just gave her some sugared water (a Jamaican cure-all). They never took her to the hospital.

When she came to school in England, the teachers noticed something wasn’t quite right and advised her to see a doctor. The doctor said that she had damage to the back of her skull, restricting the blood supply to her brain. The facilities in London meant that Veronica started getting the medical treatment she needed.

She had a seizure in her late teens and then had an operation to put a stent into the arteries in her neck head to improve the blood flow to her brain, which seemed to help at the time.

After school, Veronica worked in a factory in Battersea that made nurses’ uniforms.

In her early 20s, when she was still living at home, Veronica got pregnant and had a baby girl. The relationship with the baby’s dad didn’t work out, so her mum helped her with the baby.

Although they were no longer a couple, the baby’s dad would often call around in his bright yellow Triumph Dolomite and remained a part of Veronica and his daughter’s life.

A few years later, Veronica met Winston at a house party. He was also from Jamaica and worked in a plastics factory in South London. They had a son and, in 1978, decided to get married.

Veronica’s mum, Pearl, who by then was known as ‘Auntie P’, made the wedding and the bridesmaids’ dresses. It was considered bad luck for Veronica’s seven-year-old daughter Michelle to be a bridesmaid. Michelle remembers being jealous of her cousins getting dressed up on the day of her mum’s wedding.

The pair married in St Barnabas Church on Clapham Common, and Winston bought up Michelle as his own daughter. Her real dad was still very much on the scene. In fact, he was good friends with Winston.

Veronica got on very well with Winston’s mum. Her mother-in-law loved cooking and taught Veronica how to bake. Veronica was a quick learner and perfected the art of bun making and baking Caribbean Black Cake.

For many years Veronica worked as an Auxiliary nurse at Chelsea Hospital. She remained happily married to Winston for 37 years until he passed away in 2015.

Winston’s death had a devastating effect on her, and she was ‘quite lost’ for a while, but a friend helped her through it and reintroduced her to crocheting, which she did when she was younger.

As Veronica got older, the accident she had as a child started to affect her cognitive function, and she had another seizure in 2021. She managed to get through it, but it affected her memory. The doctors said that Veronica should have had regular check-ups since that first operation when she was a teenager. Perhaps through some bureaucratic error, she received no aftercare support from the NHS and was left to get on with her life as best as she could.

Veronica retired from nursing at 60 and now lives alone. She crochets all the time and finds it relaxing and therapeutic. She also visits a local community centre where she meets other Caribbean elders, many of which are also retired nurses. They, along with her family have been a great support to her.

Veronica still loves baking cakes, and according to her daughter Michelle, who helped me with this interview, she “still makes the best bun in Battersea.”

Gloria

Gloria was born in Jamaica in 1943. She came to the UK when she was just 15 years old. She says the reason she looks for good for a 76-year-old is that she “no smoke, no drink and no bleaching” (bleaching means -staying up late).

Gloria has had quite an eventful life. She used to be a model and appeared on several Reggae album covers. In the late 60s she worked at Bobby Moores’ leather coat factory in Liverpool Street. She told me that the England legend would often come into the factory and that he was a “decent man”.

She was working in Harrods when it was bombed by the IRA in 1983. Luckily she was in the canteen at the time on one of the upper floors so was unharmed. She’s worked for the Ministry of Defence and was working as a chef in Wandsworth prison in the 90’s during the infamous riots. Again, she was lucky that she was in a part of the prison that wasn’t affected.

She now owns ‘Gloria’s’ in Tooting Market which specialises in Caribbean groceries. The market is changing with lots of new trendy food stalls coming in but Gloria has her regulars and is doing good.

She loves living in the UK. “You will not find another country like this. If you are living in England, you are living good! There’s nothing better than the English. I’m not going to ever live nowhere else.”

RIP Gloria ‘Miss G’ 1943-2022

Manley

Manley was born in St Elizabeth, Jamaica in 1950.

When he was eight, his dad left for England and got a job working at a Lyons bakery in South London. A couple of years later, Manley’s mum also left for England and got work in the ‘Tri-Ang’ toy factory in nearby Morden.

Manley and his three younger brothers went to live in the Jamaican countryside with their grandparents. He went to school “a little bit.” It was strict, and they did a lot of caning in those days.

He also helped out on his grandparent’s farm. There were hardly any vehicles in Jamaica back then, so they used donkeys to take the produce to the market to sell.

Over in London, Manley’s mum and dad had managed to save enough money to get a house and send for their sons. So, in 1964, the four boys were flown to England into London Airport. (Heathrow). An air hostess looked after the boys on the flight. Manley remembers that they didn’t eat much because the British food on the plane looked strange to them.

It was a cold British Winter with thick snow, and Manley remembers the milk being frozen in the bottles on the doorstep. He remembers the smog and the Teddy Boys riding around on their scooters.

Manley and his brothers went to School in Colliers Wood in south west London. He and his brothers were the only black kids there. The new school took a bit of getting used to and initially, there were a few fights, “You had to fend for yourself.” But Manley made friends quickly. Like in Jamaica, the cane ‘was in force’ at this school too.

School got Manley into football. He and his new mates used to cross the river to Stamford Bridge to watch Chelsea play, and he still supports them today.

One of his aunty’s husbands, who lived in Lewisham, had a Mini. They all used to all squeeze into the tiny car and go to Southend on Sea for an outing. He used to love going on all the fairground rides. It was a great childhood.

Manley left school at 16. He had learnt how to use a lathe and became an engineer. He worked for many years at Smiths Meters in Mitcham and knew how to make a gas meter from scratch. Manley’s surname was Robinson, but everyone at work called him ‘Robbo’.

Over the years, he had 19 jobs in total. Back then, you could walk out of a job and into another the next day. Most of the places are gone now. (A Lidl supermarket now stands on the site of Smiths Meters). Manley only ever worked in engineering – he knew how to take a car apart and put it back together again but not any more because they are full of electronics nowadays.

Life was good then. Manley gave his mum and dad a bit of rent out of his wages. He got paid in a little brown envelope and earned around 8 shillings per hour (50p). If he was lucky, he got a pay rise of 1p or 2p per hour.

He’d work all week and then go to dances. They were all over South London. The Brixton Town Hall dance, The Norwood Suite as well as house dances, with 100 people crowded into the room. There was never any trouble, and nobody got drunk. People would have these little glasses of whiskey or rum with a big lump of ice topped up with a splash of orange juice or whatever. Often the dance would go on all night. Sometimes he’d go from the dance straight to work. If he was lucky, he’d ‘link up with a girl or get a ‘rub up’ dance,

Manley’s wife Jenny was also from Jamaica, and just like Manley, she came to England in 1964. Manley was driving to work in his dad’s Austin Cambridge when he first spotted her standing at a bus stop. From then on, he’d take the same route past the bus stop hoping to see her again. One day, he did, and he asked if she wanted a lift.

After dating for about a year, they married at Upper Tooting Methodist church.

The couple went on to have three daughters, grandchildren and great-grandchildren. They have been married for 50 years.

Manley has retired now. He’s doing okay. He got a private pension from one of his engineering jobs and has lived in his house for 41 years.

He has a genetic condition that means he can no longer use his legs. He started to slow down when he was around fifty. The symptoms gradually worsened as he got older. The condition also affected his brother and his paternal grandmother. She spent much of her life unable to leave her chair, but lived to over 100.

For someone who used to love dancing, swimming, and playing squash (not very well, he joked), Manley is philosophical about his condition. “It’s just a thing that runs in the family, and there’s nothing I can do about it.”

He calls his walker his “third leg” and uses it to get about. “I’ve got to keep moving; exercise is what it’s all about.”

Manley goes out in his adapted car and tries to do as much as possible. He has always gone to church. He went with his mum from when he was small until she passed away aged 89, and he still goes to the local church every Sunday.

He likes to watch football on the TV and, for a treat, will make himself a ‘Jamaican Guinness Punch.’ A bottle of Original Guinness (Not draft) mixed with Nutrament (A milk-based energy drink) and shaken well with a large splash of rum.

Manley said that the last 69 years he’s spent living in England has been pretty good, and that he doesn’t have too much to grumble about.

A few years ago, he took his mum on a long holiday to Jamaica. While they were there, they visited her sister who was celebrating her 80th birthday. It was great that his mum got to see her sister again because about a year or so later, both women passed away on exactly the same day – one in Jamaica and one in London.

Some Jamaicans dream of going back to the Caribbean when they retire, but not Manley, “I wouldn’t go back there to live, end of story. South London is my home.”

Betsy

Betsy came to Britain from Jamaica in 1960. She was just 16 and travelled all by herself. She flew in to Gatwick Airport and was put on the train to London where her Aunty was waiting for her at Victoria Station.

She got a job at a small factory in Old Street. They made sailor suits for little boys which were all the rage at the time.

After about five years, she got a job at a coat factory off Balham Grove and it was around this time that she met her husband Martin.

Life was going good, they had four children and managed to buy their council flat.

Early one morning Betsy and Martin were driving along Balham Hill when a drunk driver pulled out right in front of them. Martin was killed in the crash and Betsy was badly injured and spent 3 months on her back in Hospital. Martin was just 39.

Having 4 kids and no husband meant that Betsy had to work. Once she’d recovered, she got a job as an orderly at the Maudsley Hospital which treated people with severe mental health issues. She said that this was a very unpredictable job as some of the patients were highly volatile.

One day, she was doing the lunches and was pushing her trolley down a corridor, when a patient ran out of a room and put his arm around her. He squeezed her tightly, grinned and asked if she was okay. Betsy was terrified. She could see in his eyes that the situation could go badly wrong if she didn’t stay calm. She managed to control her voice and said, “Yes son, I’m completely fine.”

Eventually, some nurses led him away but Betsy had to sit down because she was so scared.

Betty is 78 now and retired. She has lots of grandchildren and has moved from Balham to Mitcham.

She has hip problems from the accident and still gets flashbacks from time to time. She said that even though it happened years ago, “It never really goes away.” Despite this, Betsy remains a cheerful and upbeat person, “You just get on with what you have to do.”

John

John was born in Richmond, Jamaica, in 1935. He was one of 10 kids and had to share a bed with his brothers. His family lived close to the school, which was good because John loved school.

Once he’d completed his ‘Senior Certificate of Education’, which is the same as A levels in the UK, his parents then sent him to college at Buxton High School in Kingston, where he boarded.

After college, he got work in the accountant’s office of the ‘Citrus Growers Association of Jamaica.’ All the citrus growers in the country would bring their fruit to the warehouse, where it was packed and inspected. It was John’s job to work out the value of each shipment before it was exported to the UK.

John said that Kingston was a fantastic place to live during that time, it was safe, and there weren’t all the guns and violence that there is today. John enjoyed his job, and while working there, he met Audrey, his future wife.

He was keen to go to university but would have to pay for this in Jamaica. Whereas in England, back then, University education was free.

Audrey wasn’t too pleased about him going, but John felt that England offered him more opportunities than staying in Jamaica.

He booked a flight to England through the Chinese travel service. In Jamaica, there is a large Chinese population. When slavery was abolished, plantation owners hired cheap Chinese workers to do the work of former slaves. Jamaica now has Chinese newspapers, schools, cemeteries, a Chinese freemasons association and even a ‘Miss Chinese Jamaican’ Beauty Pageant every year.

John flew into London airport (Now Heathrow) in 1961. The British houses all looked so strange to him. Everything was so grey and he remembers the fog. He said it was so thick that you could barely see at night. He thought it was wonderful when it snowed and would spend ages making snowmen. He didn’t realise that he should have worn gloves and got chilblains. It was all so exciting and new. He missed his mum terribly, but she would write to him weekly in those lightweight blue airmail letters.

Initially, he stayed in a Hostel near Victoria Station. Then John went to live with an old school friend Oswald, who had come to England five years earlier and had a house in Balham with a spare room. They became lifelong friends, and he was the best man at John’s wedding. They remained close until he recently passed away from Alzheimer’s.

John got a job working behind the counter at the post office in Tooting.

Shortly after, Audrey came over and lived with an aunt in Clapham. She got a good office job and ended up working for Wandsworth Council.

After a couple of years, she and John married at St Anselm’s Catholic Church in Tooting Bec. John was a Catholic, but Audrey was Church of England, so to get married in the Catholic Church, she had to get instructions from the priest about ‘how to treat a husband well and how to behave as wife’ (John joked that she has since completely ignored all this)

The couple got a mortgage from Greater London Council. In those days, the council would help people buy places. The couple still live in the same house today where they raised two sons who are now adults, with their own families.

Back then, the Post Office was state-owned, which meant John was a civil servant and could transfer to other jobs in the service while keeping his pension. In 1975 he became a VAT inspector in Shaftesbury Avenue in the West End of London, directly opposite Chinatown.

He would get the Northern line tube from Balham to Leicester Square every day and worked there for 20 years. He loved the job and was promoted to a senior officer. This position meant that he was allowed to retire at 60. John jokes that his bosses must be kicking themselves for the mistake of retiring people at 60 because he’s now had a work pension for over 25 years.

He was always a member of the Labour Party and would help out by delivering leaflets and canvassing. The local MP, Siobhain McDonagh, said, “John, you are doing all this work. Why don’t you become a councillor?”

John applied, and in the council elections, he won.

At 63, John became a councillor and worked mainly on the planning committee. There would be many long meetings to decide whether or not to approve a specific development.

Sometimes it was stressful because he’d have to reject some applications. It was also rewarding when he’d be out on the streets and see some of the buildings he had approved at the planning stage. John gave the go ahead to the construction of the Lidl Supermarket in Tooting. His wife shops there and says, “You can’t go wrong with Lidl”.

John is glad that he came to live in England. He has experienced racism. The worse time was in the 1980s when he and Audrey would worry about about their kids going out to play. His boys once got their bikes taken from them on Tooting Common by Skinheads.

He was a councillor for 20 years and became an honorary Alderman of London. “I’ve made my own luck. I don’t sit around and complain about things like racism. It exists, but you must deal with it when facing it. You have to make more effort, but you must prove yourself.”

John certainly proved himself because, in 2007, he became the Mayor of Merton.

At 87, John has retired from politics. But just like he has always done, he still canvasses and does leaflet drops on behalf of the Labour Party every Sunday. To him, it’s the grassroots stuff that is important. He enjoys it.

He goes to a keep fit class thee days a week, and his wife insists he keeps the house up to scratch with painting and fixing things up. He’s currently enjoying reading Michelle Obama’s latest book.

John never did go to university as planned when he first came to the UK. Judging by all that he’s achieved in the last 63 years, it’s hardly held him back.