I first came to Los Angeles in 1984 to visit my father, who had moved out here after my parents divorced. It was the summer of the LA Olympics, and I was in sixth grade. I loved the palm trees, the movie studios, and the mystique of it all. The following summer, I moved out here permanently and right away, even at that young age, I felt much more at home here than in Texas, where I had been born and raised. In my first year here, I was stopped while riding my bike to school and ended up being cast in a Levi’s commercial. I was like, ‘Wow, you show up here and they put you in a production. This is the place for me!’ I bought a Honda scooter with the money I made, and rode that thing all over town.

After that, I just wanted to have a job and make my own money. I started working at Target, and there I met a guy named José who changed my whole trajectory. I was a cart attendant and he worked in lawn and garden, and was one of those charismatic people who could completely change the course of your life. His parents were first generation immigrants, and came over here from Mexico in the 1970s. He introduced me to this Mexican street gang called Canoga Park Alabama Street, known as the CPA, and the whole cholos scene. I was just blown away by this other world that I had never before seen. It was dark and dangerous, and it enticed me in.

José was this confident, tall dude, about a year older than me, while I wasn’t very big or athletic, and I looked very young. When we met I was 16, but still looked like I was 12, with long blonde hair and skinny as a rail. I was bullied heavily at school, but the more I hung out with José, the less people would mess with me. And being around the gang gave me this feeling of power. I was probably searching for new role models, too. My dad was born in 1944, and masculinity was different back then. If I was sad, he’d say, “Suck it up. Men don’t cry.” When I got beat up at school, I didn’t tell anybody about it. I just kept it inside.

The CPA was a very violent street gang that dates back to the 1930s. It was started by immigrant farm workers who wanted to protect themselves from racism, but turned into something more criminal. There was structure to it, almost like a military-style hierarchy, and a uniform — baggy jeans, white baggy t-shirts, and white Nike Cortez sneakers. And when we drove around, I felt a real pride to be part of it. I had this sense of belonging to something bigger than myself. It was like a religion; you go to church to worship your God, but also to be part of a community of like-minded people. I was enticed by living on that edge, always flirting with danger. And then I realized the girls liked it too. Girls didn’t want to have anything to do with me when I was younger, because I looked like a little boy and they wanted all the guys that looked like men. But the more I hung out with this dangerous group, the more they would pay attention to me.

The deeper I got into the lifestyle, the more my stepmom and I would get into it in the house. We had a big fight one day, and I ran away. I ended up staying at José’s house, with his huge family. It was a three-bedroom house, and there were 13 people living in it, and I slept in a sleeping bag in the living room. My dad tried to get me to come back home, but I refused. So I took my last year of high school while sleeping in their living room, and I was really happy. They were such warm people, who let some skinny little white kid come into their home and treated me as one of the family.

As I was getting ready to graduate high school, watching the first Gulf War on the TV, I decided to join the Marine Corps. I had been told my whole life that I was small and insignificant. I really wanted to prove to myself that I was a man, and that I could hack going to war. Local guys in Canoga Park, who fought in World War Two, said they were proud of me. And that made me feel good. Then after I got out of the Marines, I wanted to join the LAPD, but I didn’t score high enough in the exam and was distraught about that. I really wanted to be a cop. So I got a job working for a Canadian telecommunication company called Nortel, doing field technician stuff. And then, out of the blue, I get a call from José’s family. He’d been killed.

I’d been told that José had been selling drugs, and I had a bad feeling about it and had tried to stop him. But he assured me not to worry, and he was the kind of guy that could just make you feel like everything was going to be okay. He was never scared, and he always knew what to do. So, he didn’t stop, and then one night he got involved in a car chase with the LAPD, and they shot him dead. I remember feeling like I was in a tunnel when they told me. Everything went wonky, and I started losing it. This was my big brother, almost like a father figure. He taught me the things my dad didn’t teach me. I jumped in my car, I had to see it for myself. There was his truck under the freeway, smashed into the concrete, and there’s a body laying under a sheet. I see these big-ass white Nikes sticking out, and that’s José. That was the last time I saw him, and it messed me up.

From that moment, I started to hang around with the gang more again, and I started to take more risks. I was mad at José, mad at the cops, mad at myself. Secretly, I wanted to die, and it just took me down that dark path. Then one night, we were partying and we wanted some more weed, so I called up my friend who lived in the neighborhood. I drove down and we met by this alley, and the three other guys got out while I stayed in the car. Then, I heard some fighting, so I opened the door to step out and I heard a gunshot, so I slammed the door shut and start reversing the car our of the alley, then one of the guys I was with jumped in front of the car. We take off, and I’m like, “What the f*** happened?” He tells me someone got shot in the head. The guy died, and the next day there was a knock on my apartment door. It was the SWAT team. They knew I was a former Marine, and a gang member, wanted for murder, so they came ready for combat. They were taking me into custody dead or alive. They ended up charging me with first degree murder, conspiracy to commit murder, three counts of armed robbery, assault with a deadly weapon, assault with a semi-automatic handgun, and the gang allegation. And the next day, when I was in custody, I remember my attorney telling me, “Brian, it doesn’t look good, they’ve filed special circumstances.” I said, “What’s that?” And he said, “The death penalty.” I remember dropping the phone from my ear and saying to myself, “I can’t die in here.”

So, I’m in the Los Angeles County jail as a murder suspect, with the real bad guys. I remember getting in the elevator with the bailiff, with my head down, and he hits me in the chest, and said, “Hey, you’re gonna beat this. But I want you to remember one thing. Friends are like buttons in this elevator. Some take you up, and some take you down.” And right there, that guy gave me a little bit of hope. I held onto that for the entire year as I fought the case. The victims kept coming into court and changing their stories, while my story stayed exactly the same because it was the truth. The main point was, if I didn’t go to that alley to commit a robbery, then I couldn’t be charged with murder. And I did not go there to commit a robbery, it was a drug deal. Eventually, the judge offered me a deal. I got two years in prison for accessory after the fact, because I knew somebody had got shot and I didn’t call the police. She was very fair and I appreciated that. And she actually saved my life by still sending me to prison, because I think if they would have let me out right then, I would have gone straight back into that world. You don’t really learn your lesson if you get away with it.

That time in jail taught me a lot about myself. You’ve got to suck all of your emotions down into some dark place inside of you, and you can’t show any type of fear. You can’t show any type of sadness. Even if you want to cry, you don’t cry. When I got on that bus to go to prison, inside I was all spaghetti, my heart was pumping, and my brain was so turned on that my senses were on fire, it was like being in combat. I definitely changed my mindset in jail, but it wasn’t like the movies, with ‘Eye of the Tiger’ playing as I turned my life around. But I read some books, learned some stuff, and I decided that when I got out of there, I was not going to let anything hold me back. The worst part of prison was the conversation. It was everyone making excuses. I knew I was never going back into gangs again. I was never getting in trouble again. I was never going back to jail. I was going to do the right thing. I was going to be somebody. And I got out of jail with a new clarity: I lost everything, but I’m not dead. I can build this back. I’m going to try really hard and just never give up.

I remember the day I got out of prison, my father picked me up. He’d been at court too, throughout my case. He’d been working in Germany and flew all the way back to be there. And when I saw him at the gates, it was not a hug, but a handshake. But I am so grateful to him for being there. My father was never able to tell me he loved me. He just couldn’t get those words out of his mouth. But there are so many love languages, and him flying from Germany, to come get me out of jail, was his way of saying it.

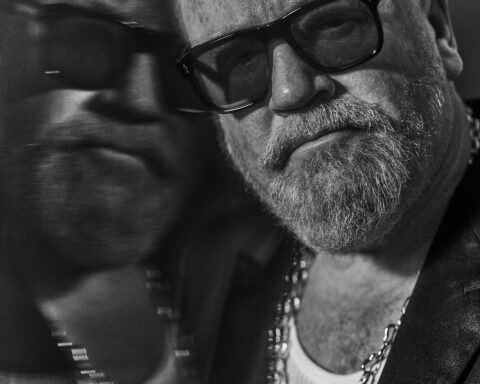

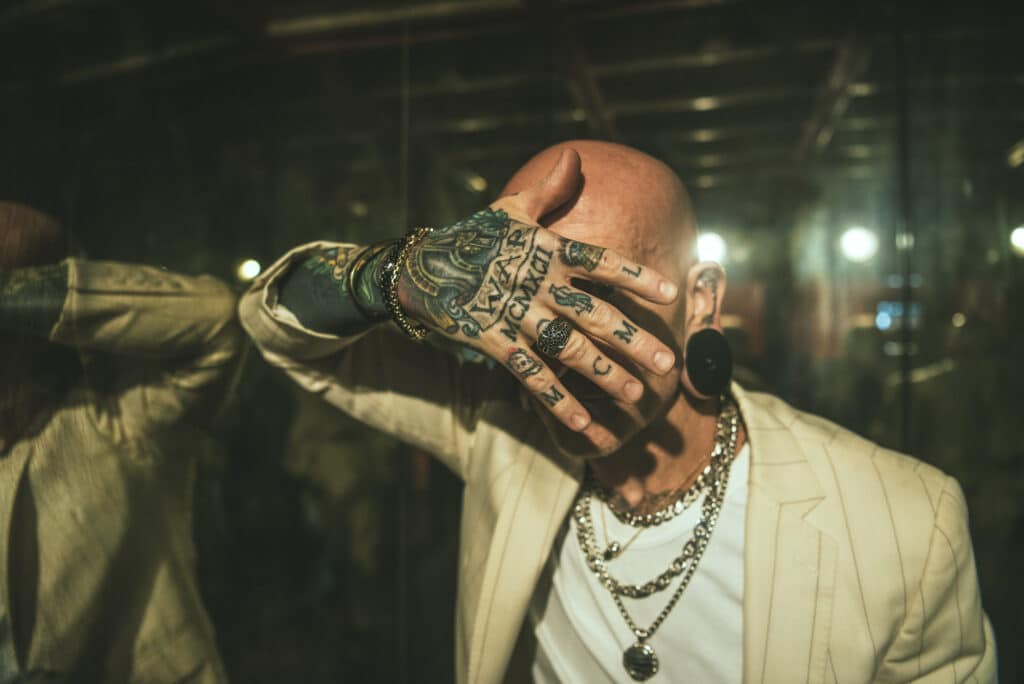

When I was released from prison in 2000, I had all these jailhouse-style gang tattoos I wanted to get rid of. Every time I looked in the mirror, I saw the old me and I wanted to start fresh. This guy at the gym told me about Body Electric on Melrose Avenue, so I started going there and getting tattooed. Then the shop came up for sale and I knew I wanted to own it. So I cashed in my stock options, my pension, my 401k, and the previous owner agreed to carry the loan. I had no money left, so I had to sleep on the piercing room floor for about six months. I got death threats from tattoo artists at the start, because I wasn’t a tattoo artist and was just a shop owner, trying to make money off their art. All my staff quit on me. But the more people told me I couldn’t make it work, the more determined I became.

When I’d been there a couple of months, the previous owner, she was called Bernie, told me that in order to be respected I had to find something to do. She made me pierce my own nose, and that lit something in me, that I could have a role here. So I mastered the skill, which is simply a form of decorating, and I’m just a good decorator. I also like people. I’ve been through so many different facets in life: military, gangs, corporate, jail. So I know how to talk to people. When a client comes in right now, I don’t see them as money today, I see them as a relationship and money year after year. I want your friends, your family, and your kids to all end up coming here. Business is all about relationships and trust, especially when you have a needle in your hand!

Adele comes to my shop from time to time. I love her to death. She’s so down to earth and silly, a lot of fun to talk to. I’ve had Jennifer Lawrence in my studio, Rihanna used to come in back in the day, and working with Beyoncé was a real gamechanger, and I was lucky enough to have her trust me, and work with her for a year. You’ve just got to do good, dependable work, and not talk about them too much.

The trends in men’s piercing have changed a lot since I started. It used to be one piercing in your left ear if you were straight, or right ear if you were gay, and the occasional big hoop in the cartilage in the upper part of the ear. Now I’m getting men trying everything. They’re coming in and doing a constellation piercing, where there’s a multitude of piercings in the ear, and they’re embracing different gemstones now. The stigma is breaking down surrounding what’s good for women and what’s good for men. And I think it’s cool, because I don’t think anybody should be able to have ownership of any piercing. I pierced my navel a couple of times, just because everyone said it was only for women. I was like, ‘Who made these rules?’

The mindset of what it means to be a man is changing. Just because you have three piercings in one of your ears, doesn’t mean you’re less of a man, or more of a man. I look back at my youth, and some of the decisions I made, based on what I thought it was to be a man. Well, now I know there are a billion different ways to be a man.