‘Joyland’ is the first film out of Pakistan to premiere at the Cannes Film Festival, and deals with the inner longings and dynamics of a middle class family in Lahore, living within the strict expectations of a patriarchal Muslim household. Multi-layered, nuanced in character, and visually exquisite, it landed the prestigious festival’s Un Certain Regard Jury Prize, which rewards artistically daring films, and the Queer Palm award for LGBT-themed movies. Amid unprecedented accolades for a Pakistani film, it was also named Best International Film at the Independent Spirit Awards earlier this year, and was the first film from the nation to be shortlisted for the same honor at the Academy Awards.

The main protagonist Hadid (Ali Junejo, making his screen debut) remains living at the family home under the watchful eye of his dominant father (Salmaan Peerzada), whilst his wife (Rasti Farooq) enjoys working at the local beauty salon, breaking the norm as the breadwinner of the couple. Unemployed for several years, Hadid finally lands a job at a local burlesque theater, but too ashamed to admit that he is in fact learning to become a background dancer, he instead tells his family that he’s been hired as the venue’s manager. As he becomes immersed in rehearsals for this new gig, Hadid falls under the spell of trans woman and performer Biba (Alina Khan) and thus begins an intimate and revelatory relationship which subtly mirrors the various private yearnings and limitations of other members of his family. Each and every character is both written and performed with a depth and raw honesty that naturally draws the audience into their individual and collective inner lives, disarming prejudice and eliciting empathy.

Since 2011, Pakistan has only produced an average of around 15 features per year, and ‘Joyland’ was banned by the country’s conservative government five days before it was due to hit screens. Employing a fierce social media campaign driven by a determined cast and crew, the trans community, and Nobel Peace prize winner Malala Yousafzai, the ban was lifted in time for its release, although it still remains prohibited in the Punjab state where it is set.

Defending the film in a letter published in Variety magazine as they fought the ban, Malala wrote, “’Joyland’ is a love letter to Pakistan, to its culture, food, fashion and, most of all, its people. How tragic that a film created by and for Pakistanis is now banned from our screens because of claims it does not ‘represent our ways of life’ or ‘portrays a negative image of our country.’ The opposite is true — the film reflects reality for millions of ordinary Pakistanis, people who yearn for freedom and fulfillment, people who create moments of joy every day for those they love.”

To enable the film to be released in Pakistan, around three minutes were cut from the original version screened at Cannes. A bona fide crowd pleaser, ‘Joyland’ won standing ovations at the French festival, managing to deliver and connect beyond its central trans-cis love affair. This is not a film focused on that singular theme but offers a deep, witty, and sometimes painful dive into cross-generational, religious, and societal tenets that make up the moral backdrop of this middle class family. It was released in New York and Los Angeles theaters in April, and is now being rolled out across US cinemas before being made available on home streaming platforms later this year.

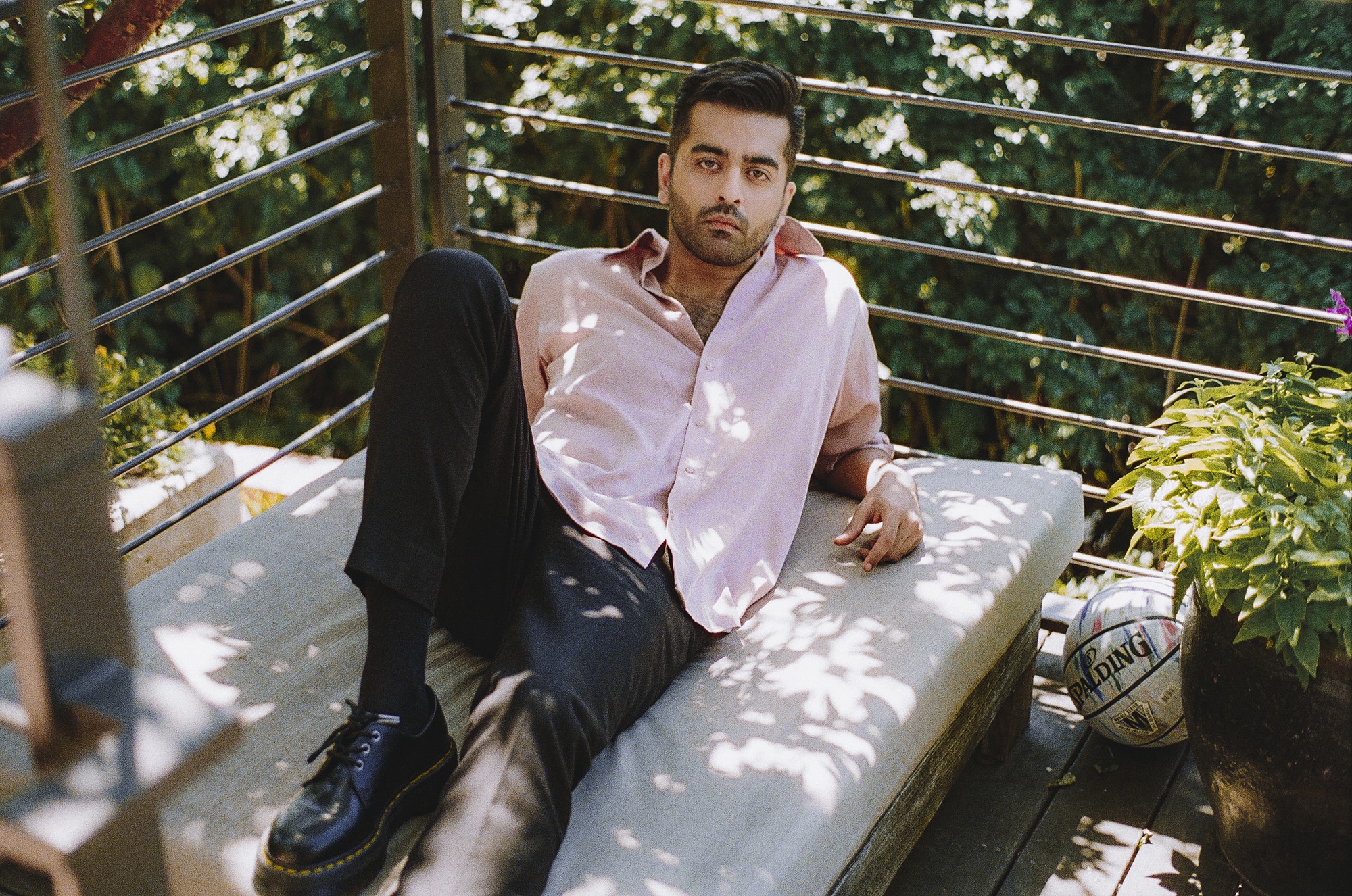

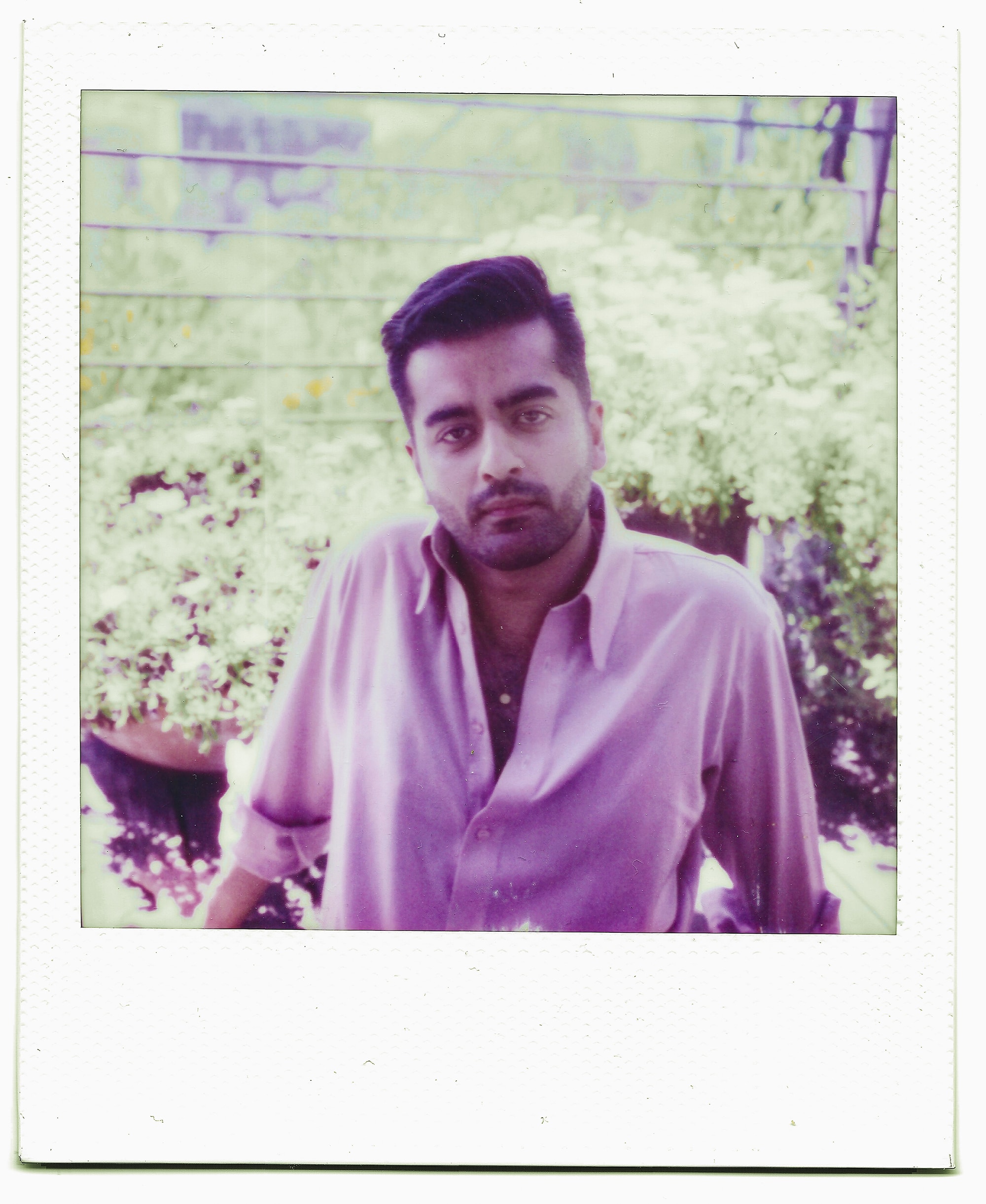

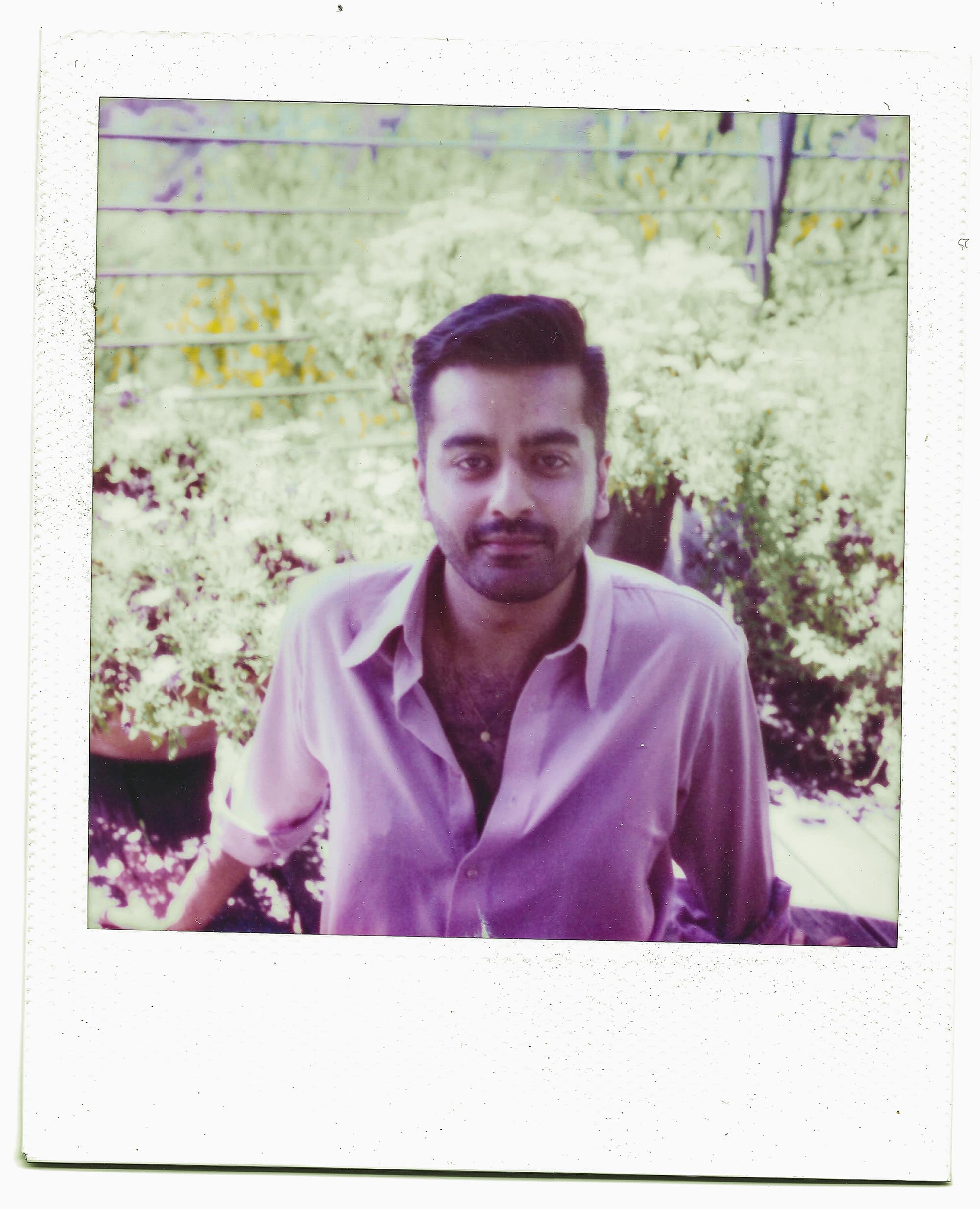

Saim’s deft script and directorial debut succeeds in revealing the mutual emotions we all experience, whichever way we choose to live and identify. Set against a palette which showcases the vibrant beauty and culture of Lahore, one comes away feeling deep empathy for each character’s journey, humanity, and struggle — regardless of their rank within the hierarchy. And as a very impressive first feature for Sadiq, it leaves the movie fan with a sense of excitement as to what the future holds for this talented 32-year-old filmmaker.

Tell us a little about your background, and where you grew up.

I was born to a standard middle class family in Rawalpindi, Pakistan. My dad was in the army, my mother was a housewife. Academics was a big part of growing up. All my parents cared about was that you must be a good student, get straight As. That was something that I was never interested in, but to keep my parents happy I knew that I had to do that. Because my dad was in the military, we would move all across the country. And that was both good and bad. I never got to create a home anywhere because we would move and settle in one school and then there would be a new posting and we would go somewhere else. But I got to see the country and many cultures, the many layers of how the country was functioning. And so I grew up and did my undergrad in anthropology [at Lahore University of Management Sciences].

Then I broke the big bomb to my parents, that I wanted to do film. And they were luckily quite supportive about it. I didn’t expect them to be. It restores your belief that people are more than you give them credit for sometimes. You assume that a person might not be okay with something, but I found out they were. I was an assistant director in Pakistan for a year, then I went to Columbia University and did my masters there.

What access to films did you have growing up?

Growing up post the 2000s, the internet access really benefitted me because earlier on we had VHS cassettes, but the only films we would get in Pakistan would be the big Hollywood movies like ‘Jurassic Park’ and ‘Titanic’. Television was doing really well when I was growing up in Pakistan, we had our own local television which was sensitive and nicely done. But post dictatorship, which was right before I was born, film unfortunately wasn’t. So we didn’t have any cinema culture of our own so to speak of.

I was obsessed with watching movies and acting out scenes from films for fun. And I got a camera and started taking pictures. So the intent was always there in terms of storytelling. I was introduced to a lot of American, European, and Iranian films — as well as Indian films that weren’t mainstream, the more independent arthouse films from the ’60s and the ’70s, by filmmakers that really influenced me.

What was the genesis of the idea for ‘Joyland’?

I was still in school at Columbia, and we had to write a script for the class. It was a year-long course and we had to complete the first draft of that screenplay in that year. I get bored very easily of story ideas. I think I’m a genius one day, and the next day I think it’s the worst idea in the world. So I wanted to come up with something that could sustain my own interest for a year.

The first idea was this man, woman, and trans woman love triangle, set in a middle class household in Pakistan in a film that spoke about patriarchy. That dramatic set-up allowed me to speak about a lot of things that I now know retrospectively were very personal to me. It didn’t start out as a personal story, it just became emotionally autobiographical, because the plot of the film is very different from anything I’ve ever experienced in my life. But the characters, their inner truths and inner lives, are very similar to either mine or people I’ve grown up around.

How has the trans community reacted to the film?

The reaction from the community has really been one of the nicest things that has happened in the past year. They’ve been incredibly supportive, not just in their reaction but also in terms of making the film. Every character in the film who’s trans — not just Alina’s character Biba, but at her house, at the wedding — are all actual trans people who are not actors but came for [filming] that one day. They were so excited that there was a story that included their lives and their culture. So buses and buses would just show up with so many clothing options. They were so invested in the film and the idea that one of [their community] was the lead, which is something that was not imaginable to them before. So they’ve really taken it up as their film, [with regards to] the controversy and the ban back home. One of the biggest voices that was amplifying the cause of the film, and the fact that we wanted the film to be released, was the trans community.

How does the Pakistani trans community compare to others around the world?

Their community is so indigenously rooted that it’s hard to compare it to the US or the movements anywhere else in the world. What’s not known about them is the fact they’ve had centuries of existence [in Pakistan] and it wasn’t always an existence of discrimination. Historically speaking, they were a big part of the culture in a very overt fashion. Pre-colonization, they were associated with poetry and there was never an idea that they were an ‘otherized’ community. Unfortunately, that idea was imported with colonization when the British came, and so the discrimination is imported. A lot of people think that the trans movement or the LGBTQ movement has been imported from the West into Pakistan, but it’s the other way round. It was the discrimination that was imported. And now we’re in a situation where the community is struggling to regain its past glory, without feeling like it’s borrowing those ideas from the West. But they’ve been able to pass legislature that is very unique and progressive. They can self-identify their own gender in Pakistan, which is not something you can do anywhere in the world apart from, I think, 10 or 12 other countries. So on some level, despite the fact that the overall country is so conservative, the trans community is spearheading a very progressive movement.

How did you react when the Pakistani government banned the film?

We couldn’t react emotionally to the ban. I think the entire team and I looked at it in a very pragmatic way. We decided we are not going to take this personally. This has happened before to many films, and it will keep on happening. Fortunately, we have a film that has created a certain amount of buzz based on its laurels, whether it was going to Cannes, Malala’s association with the film, or [Oscar winning British/Pakistani actor] Riz Ahmed’s association with the film. We knew that we had an audience that wanted to see it, despite it being an indie film. So this meant that we could capitalize and create some kind of resistance movement. And we did just that.

We had six days because the film was banned on the 11th or 12th of November, and was supposed to be released on the 18th. So we were like, “We’re not going to sleep, we’re not going to react emotionally. Whoever needs to go and cry, there’s the other room!” We were literally huddled up in my apartment in Karachi, the cast of the film, the ADs, everybody. And some of the cast members were not on Twitter, so they created their accounts there and then, the day the film was banned, for this very reason. It was like a war zone in a certain way and we were kind of getting a kick out of it. “Oh it’s trending now, the Prime Minister has taken notice, this is happening, that is happening.” To be able to get the film unbanned within five days was something that I take a lot of pride in.

How did Malala become involved?

We premiered the film at Cannes, and she heard about it and met one of our executive producers. She asked for a link, was super-generous in her response to the film, and got in touch with us. We got on a Zoom and she said, “I want to help in whatever way I can.” Literally two weeks later her credit was on the film and a deal was signed. She’s such a down-to-earth, gentle human being and has really been the most beautiful force behind the film.

Why is storytelling so important to you?

Pakistan and particularly Punjab, which is the state I’m from, has a long history of storytelling as a tradition. But growing up, I wasn’t very familiar with it. My family isn’t artistically inclined at all. It was something I picked up from within myself because it was my only way of making sense of the world. I think the ability to lose oneself into a story, to have a profound connection and find things about your life even though what you’re seeing on screen has nothing to do with you, is something that only movies have done to me. And I think that’s true for a lot of people. Movies teach you about humanity, and foster empathy and compassion for people that you would have no way of meeting in your life. For example, ‘Joyland’ is now playing in New York and LA. There is no way you are going to encounter a trans person, a housewife, or a timid and meek middle class man from Lahore while sitting in LA if not for a movie. To see how their life functions, and how similar they are to you. I think it’s something that restores your belief in our collective human experience.

‘Joyland‘ is in theatres now