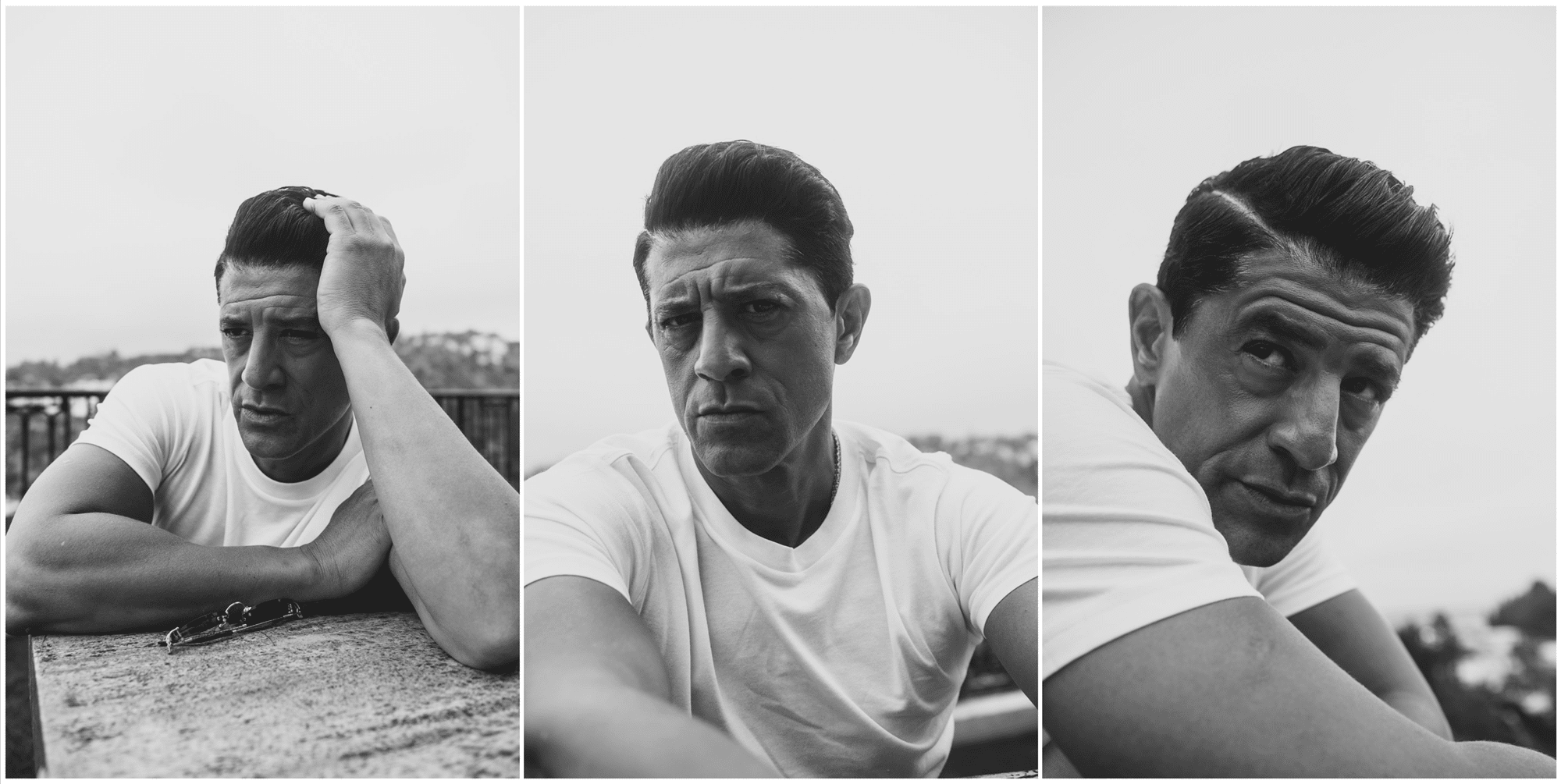

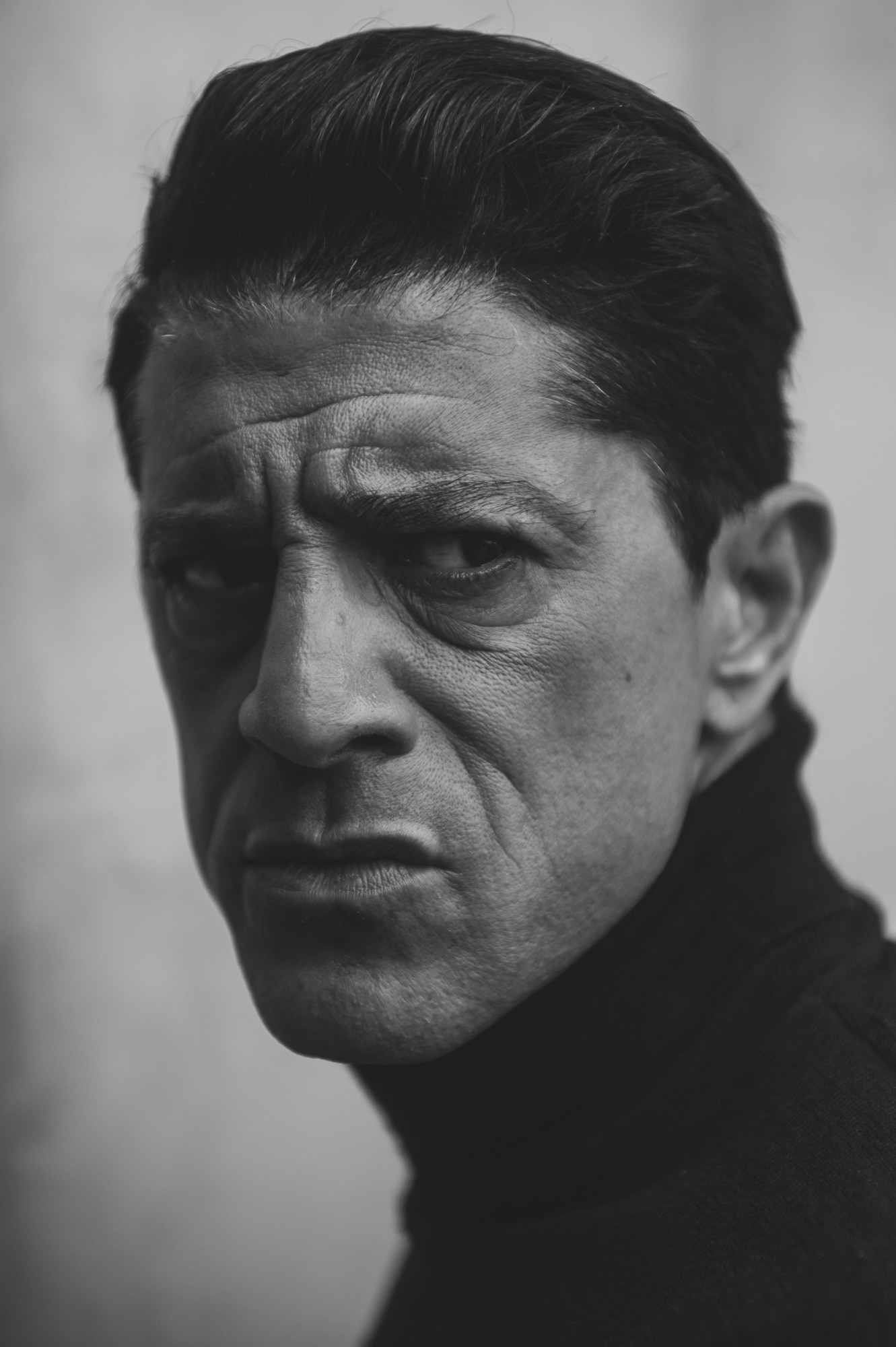

Despite spending three decades standing toe-to-toe with the Hollywood heavyweights — in a career launched with his starring role in the hard-hitting French indie film La Haine in 1995 — actor and boxing fanatic Saïd Taghmaoui has never had a publicist before. And it shows.

We’re talking inside a sleek and modern home in the hills of West Hollywood, which must be worth north of $10 million, and is owned by one of Saïd’s many high-flying friends. Reclining on luxurious sofas in the cinema room, this is not an unusual setting to meet with a movie star in this city of excess. But normally, the polished location would be mirrored by the carefully-curated content offered by the interviewee.

But not this time. Today is different, because Saïd is different. I open with some of the friendly chatter that is typical to kick-off a celebrity interview. I explain our mission at Mr Feelgood, to have honest conversations that could help our readers to navigate their own challenges, and invite him to share his story. This is Saïd’s first in-depth U.S magazine interview — he’s recently hired his first PR after a lifetime of declining to engage with the Hollywood publicity machine — but he doesn’t need warming up.

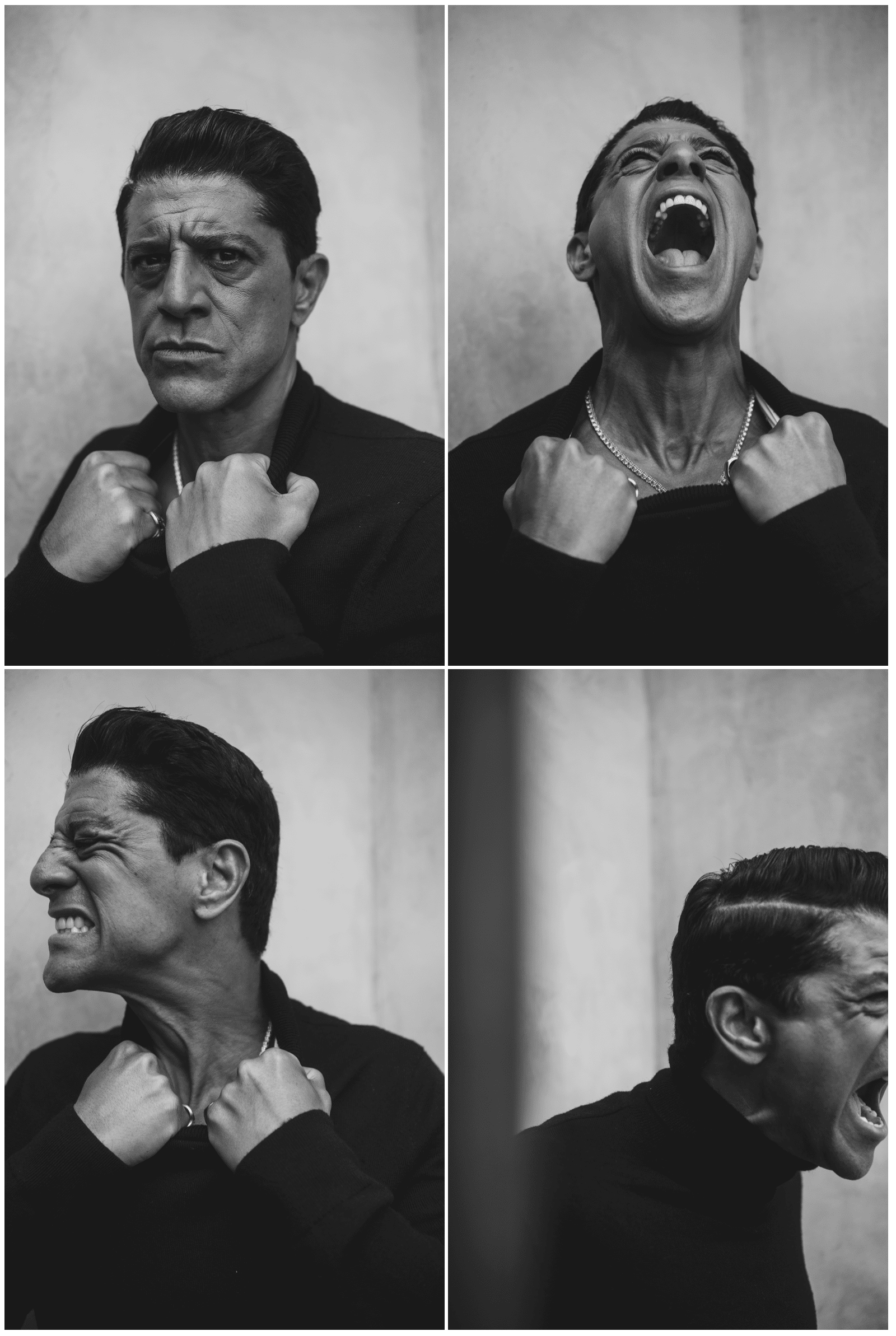

“I grew up in a ghetto in France, a very tough area,” he says. “A lot of people didn’t even know these French ghettos existed before we made La Haine. We were nowhere near the movie business, but had an opportunity to make this movie — to print our lives on film.

“The movie became such a classic, but then I had to deal with reality. There were three stars of that film: a Black guy, Hubert Koundé; a white guy, Vincent Cassel, who was the son of a big star in France; and myself, a young Arab from the hood. I co-wrote that movie, so there was my life, my soul, my blood in there. But who after that movie became a superstar? The white guy.

“It was a tough lesson that even when the subject is my own life, my own problems, my own people, my own culture — they are still going to take it, use it, and win. But I didn’t give up on my dreams, I just worked harder. That injustice became the fight of my life.”

I’m left reeling a little by Saïd’s immediacy. I’d usually expect some gentle sparring before these big swings. It is clear that, 28 years after the release of one of the most iconic films in French history, Saïd has something to get off his chest.

“Let me tell you a little story,” he continues, bouncing cross-legged in the oversized chair. “When we made that movie, we didn’t expect it to do anything. We were doing it for us. But it was such a big success they could not ignore it in the César Awards, which are the French Oscars. They couldn’t hide us away, even though we didn’t belong in that world.

“But Cassel was already part of that family, because his father was big star. To cut a long story short, the Black guy and myself were nominated as up-and-coming actors, as was Cassell. But Cassel was nominated for Best Actor too, so he got two nominations. This was a movie where the three stars all had the same size role. But for the same job, the same work, they gave him two nominations. They treated him as the lead, and us like we were lucky to be there. It was so painful. And that story says so much about the system that we entered.”

At this point, we’re just eight minutes into an arrestingly honest — and also utterly wild and unruly — conversation that would end up spanning several weeks. There would be multiple unexpected phone calls; dozens of text, video, and voice messages; and Saïd even drove an hour to my home on a Saturday morning to meet my family (without telling his new publicist — a charming act of spontaneity in this all too scripted town).

Our initial interview took place a few weeks before the riots that erupted in Paris — and elsewhere in France — following the fatal police shooting of Nahel, a local teenager of Algerian and Moroccan descent, during a traffic stop near the French capital on June 27.

That tragedy would add fresh significance to sharing Saïd’s story. He was born in France of Moroccan descent, and rose from an impoverished upbringing in the same tinderbox Parisian suburbs — known as banlieues — that were depicted smoldering on screen in La Haine after police brutality left a young Arab man in a coma, and ignited again for real in the latest political and racial unrest.

“France has a very tricky story with immigration and colonization,” he says. “My family ended up in France because they colonized our country, Morocco, a long time ago. And France f***ed up the integration, big time.

“We were very poor, and would do anything to survive. I would steal to put food on the table, or because I didn’t have a pair of shoes to wear. This was not about wanting nice things, it was about wanting dignity. I was one of eight siblings, but two died. It was the 1970s, and when the heroin started entering the ghetto no-one knew how addictive it was. My brother managed to stop, so at least he had that dignity, but he already had AIDS…”

For the first time in our breathless exchange, Saïd is sitting still, and his energy momentarily subdues.

Saïd landed his life-changing debut role in La Haine thanks to his livewire reputation on the real-life streets that the film sought to capture — coming to the attention of the writer and director Mathieu Kassovitz due to his prominence in the local hip-hop and graffiti circles. Then, after the international success of the movie, he attracted interest from filmmakers around the world. He couldn’t speak English, but took a part in the 1998 film Hideous Kinky alongside Kate Winslet. “I learned my lines phonetically,” he explains. “If you asked me anything in English outside of my lines, I was lost. After that movie, I thought, ‘If I’m capable of that, who the f*** is going to stop me now?’”

He continued to self-learn his acting craft, and the English language, on movie sets and in libraries. Despite rarely stepping foot in school as a youth, he’s now well-versed in classic literature. “The rhythm of a great author is amazing,” he says. “Literature saved my ass. Proust saved my ass. Tolstoy saved my ass. Dostoyevsky saved my ass. The way they see the world, and are able to translate it, is magical.”

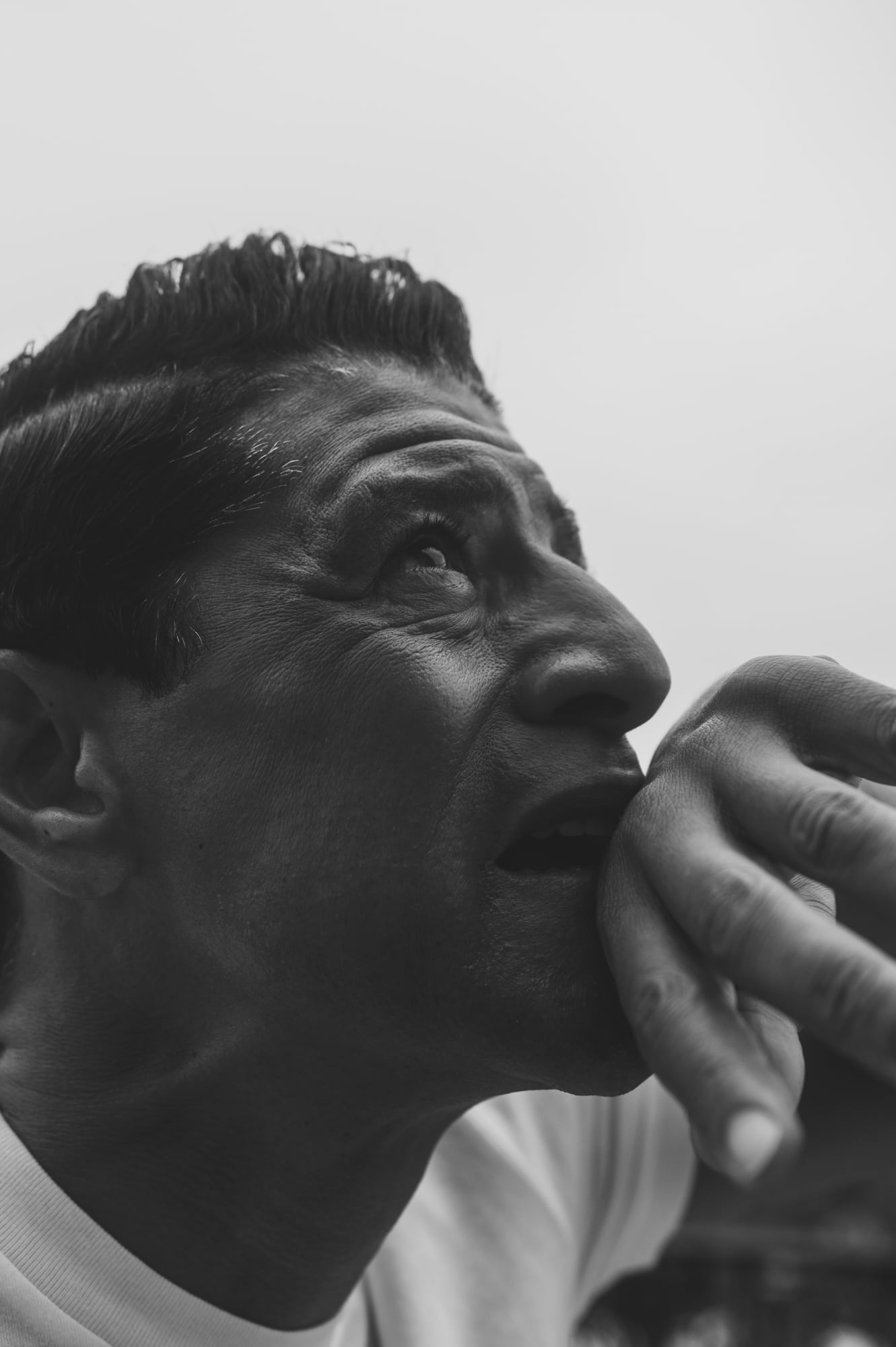

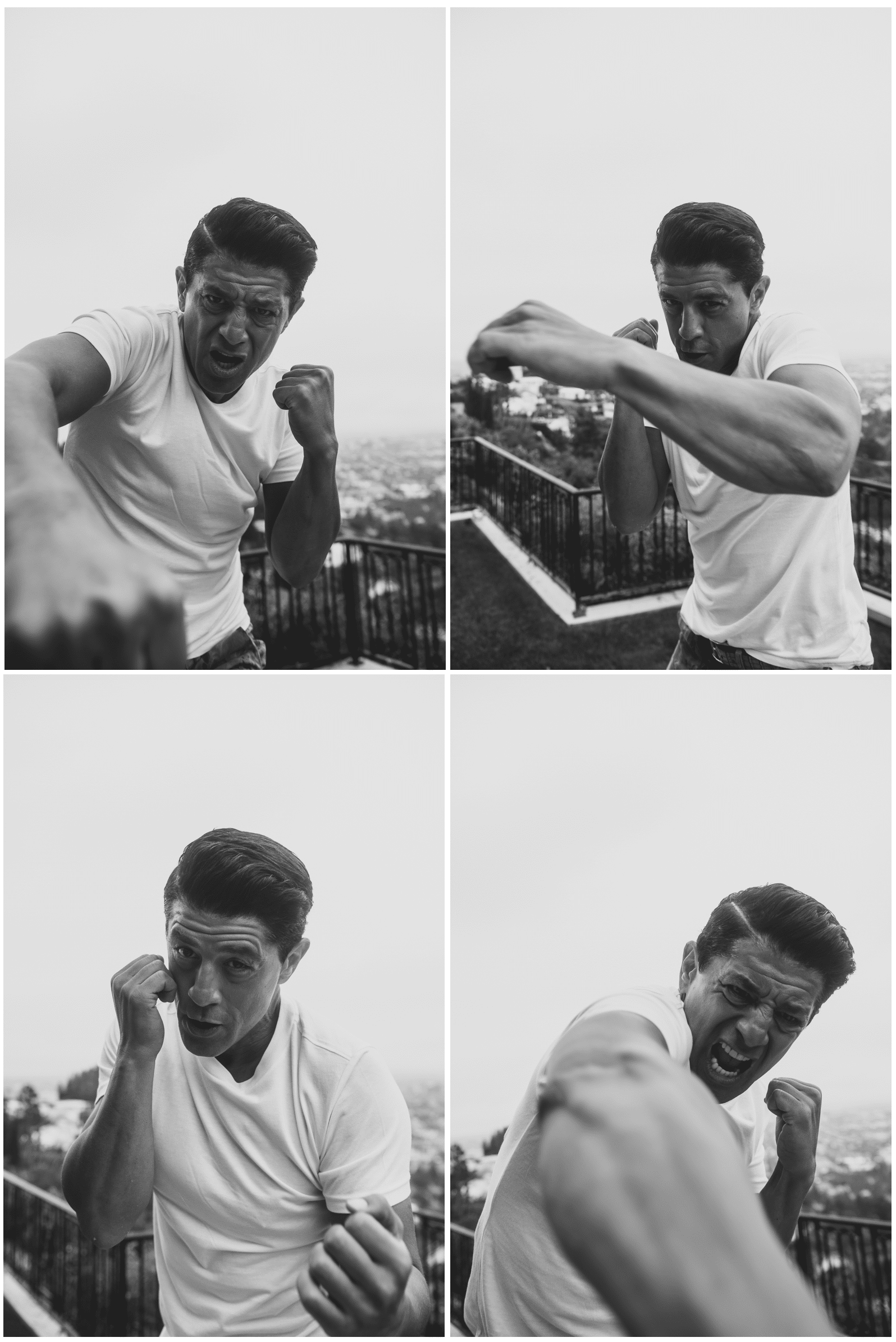

Saïd, now 50, says his mentality comes from his boxing background — entering the ring as a child into rising to second in his weight division in France. He remains obsessed with the sport, training daily and owning a slice of a management company that looks after professional boxers including Vasiliy lomachenko and Oleksandr Usyk.

“From boxing, I learned everything that helped me become a man,” he explains. “Dignity, fear, discipline, respect. All these things. Even these days, boxing is the backbone of my life. Not the movies, that world is very unstable. Boxing gives me stability in an unstable world. Success comes with no instructions, I’ve seen so many actors that went crazy on drugs. Boxing is the truth. Boxing has saved my life.”

After a rare pause for thought, he continues, “One of the secrets of life is learning to breathe properly, and boxing has taught me that too. If you know how to breathe, you know how to live. When you’re acting, and standing in front of a camera, it’s not a natural situation. But if you know how to breathe, you have control.”

Speaking of control, I rarely have any over the direction of this interview, which quickly turns into Saïd enthusiastically showing me the contents of his phone; varying wildly from videos of him boxing, to hanging out with celebrity pals including Mark Wahlberg, and riding horses on the beach in Morocco. (He learned to ride while filming Hidalgo with Vitto Mortenson and Omar Sharif in 2004, and now owns several horses in his homeland.)

And from the screen emerges another surprise. His greatest passion in life, as the hundreds of pictures and videos on his phone attests, is a Moroccan orphanage called Essaouira Darna that he began funding seven years ago, after stumbling upon the facility while riding his horse though the town. Since then he has dedicated a huge amount of his time and money to the project, giving his life new purpose.

“There are 57 kids in the orphanage,” he explains. “57 young souls, no better or worse than you. I spend two or three months every year with these kids. I’ve learned so much from them. These are kids with no mom, no dad, no brothers or sisters — nothing. And they still have happiness and joy. I give them everything that I didn’t have — education, culture, art, games. I don’t have kids, I’m not married, I don’t have a girlfriend. These kids are my family.”

Judging by Saïd’s proud smile, both now and in the videos he shares, it’s in this orphanage that he’s happiest. It’s a world away from Hollywood, because Hollywood is not Saïd’s world. But that hasn’t stopped him building an impressive body of work — in fact, it’s probably helped it. His unpredictable energy, the type you can’t teach at acting school or in media training, is what makes him so compelling on screen and in person. He’s had roles in movie hits including American Hustle, Wonder Woman, and John Wick: Chapter 3; appeared in TV classics including Lost and The West Wing; and featured in several strong projects based around America’s military engagement in the Middle East — from the brilliant 1999 David O. Russell black comedy Three Kings, to the upcoming Tin Soldier alongside Jamie Foxx and Robert De Niro.

“I love my craft,” he says. “But there’s the other side of this business that I hate — the glamour, the prizes, the bulls***, the ego.” Saïd is still fighting the system, even as he tries a more orthodox style. “For the very first time at 50 years old, I’m working with a publicist. Until now, I’ve just relied on my skills as an actor. But I thought if it could help me get some better movies, and help my other causes, then why not?”

Almost a month after our initial conversation, Saïd called me from the epicenter of the riots in Paris, where he is filming a new movie with the legendary director John Woo. The violence has echoes of the protests in the U.S in 2020 following the death of George Floyd — with oppressed groups fighting back against the police’s excessive use of force against minorities.

“It’s literally war-time in my home city,” he tells me. “But I grew up seeing violence every day, because I’m an Arab in France. Many people don’t care what you’ve done in your life, just what you look like. Is it not the quality of your soul that should define who you are?”

And referring to the death of Nahel at the hands of police, he adds, “That s*** has happened a million times. But normally there is not a camera around. That’s what was different this time.

“A policeman should be like a teacher. You need to be a very wise man because you have a gun and can take the most precious thing on earth, which is life. But they have given that great responsibility to too many basic motherf***ers.”

Despite almost three decades passing, there are sorry similarities between the plot of La Haine, set within the high-rise Parisian estates after a young Arab man is left gravely injured by police, and the real-life situation currently unfolding in France. Filmmaker Kassowitz started writing La Haine in 1993, on the day that Makome M’Bowole, a 17-year-old from Zaire, was fatally shot in police custody. So how does the current political and social situation in the country compare to that captured in this now-iconic black-and-white film?

“It’s worse,” says Saïd, without hesitation. “Way, way worse. Back then, there was less propaganda, less bulls****, less screens. There were more educated people with common sense. People cannot focus on a book these days, they are hypnotized by their phones.

“In the 1990s, there was hope that we could fix it. A few years after we released La Haine, it was the 1998 World Cup, with [the French-Algerian star player] Zinedine Zidane, alongside Black people and white people on that team. There was real hope we could all come together. But today, I feel there is a lack of great human beings to come together, talk, and make big decisions based on values not personal interests.

“France is supposed to be one of the most civilized countries, so it is sad to see that everything starts and ends with violence. We are the supposed to be the country of light — the country of Émile Zola, of Victor Hugo, of Voltaire. But we are losing our shine. It’s time for people to sit down at the table and try and fix what is broken.

“I made it out of the hood through hard work, luck, and some talent. I promised myself to never betray where I’m from. But I was a miracle. And now I want to be the light that guides others out of that situation. We need to give others like me a helping hand — to love them, and to listen.”

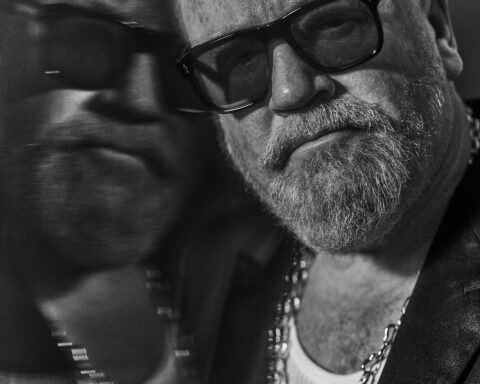

Grooming by Barbara Guillaume