She was walking to the Middle School one crisp autumn morning when it happened. She stopped to tie her shoelace and a van pulled up beside her. The man behind the steering wheel rolled down his window.

“Hey there,” he said with a kind smile, “It’s pretty cold out this morning. I just dropped my son off at the Middle School. Would you like a ride?”

The girl didn’t think twice. She stood up and bolted in the opposite direction, down toward some local businesses. She ran hard and didn’t look back until she reached the shopping center.

Out of breath, she ducked into a small cafe and looked out the window. She couldn’t see the van anymore but decided to sit in the restaurant for a while. The man in the van seemed nice enough, and maybe he was just trying to be helpful. But instinct told her to run.

An hour later the girl made her way to school. One of her teachers asked why she was late for school and where she had been. She started to cry and explained what happened. The teacher took the girl to the school’s main office, and administrative staff phoned the police department.

I was a young police detective enjoying a vacation day at home, when my Sergeant phoned me about the incident. He needed a drawing of the man in the van, and I was the only composite sketch artist in our police department.

Local news media got wind of the incident, probably from their police radio scanners. When I arrived at the police department, a reporter and cameraman were already there.

I grabbed my drawing materials and was introduced to the girl and her parents (who arrived at the police department shortly before I did). The girl looked frightened and nervous.

“Fear is the tax that conscience pays to guilt.” -George Sewell

I explained to the parents that I was a composite sketch artist, and that I needed to interview their daughter alone. The reason for this was to eliminate any undue influence from the parents.

Drawing a composite police sketch is a complicated, slow process. The artist must carefully interview the victim, and form a general idea of what the suspect looks like. From there, the drawing goes through many adjustments, until a likeness is rendered. It usually takes a few hours.

However, this time it was different. We were done in about twenty-five minutes. And I learned an important lesson about people of all ages.

Check your ego at the door

Early in my police career, I began drawing cartoons of my coworkers and their professional exploits. The cartoons provided some laughs and levity in an often stressful job.

Against my better judgment I sometimes lampooned our police administration with silly cartoons. Dumb move. The Chief took note of my artistic talent and sent me off to forensic art school. Next thing I knew I was in Anaheim, California for a week-long training class in forensic art.

The composite art school was fascinating and I learned a great deal about interviewing, observation, and rendering faces. One of our final exercises was to sit down with a “witness” and draw a composite sketch from his/her description.

The “witness” was merely a fellow student who was given a minute to study the photo of someone’s face. The photo was then taken away and the student would be questioned by a fellow student who had to draw the composite sketch.

It was my turn to draw a composite sketch and I began interviewing the “witness.” She described the suspect but I couldn’t believe the features she was telling me to render.

“Doubt is an uncomfortable condition, but certainty is a ridiculous one.” -Voltaire

I found myself several times asking her “are you sure,” and “did his eyebrow sit that high on his forehead?” Each time my “witness” stuck to her guns and insisted her description was accurate.

I neared the end of the sketch and my “witness” said the drawing looked a great deal like the “suspect” (or rather, the photo she had studied). Looking at the strange face I rendered, I felt sure I was going to fail the class. A bit depressed, I submitted the drawing below.

After the students completed their sketches the instructor did a critique of each one. When she got to my drawing the instructor asked the students for comments. There were a few laughs and someone said, ” It’s the Pablo Picasso of composite art.” With that, I was looking for my eraser to throw at the smart aleck.

“Check your ego at the door. The ego can be the great success inhibitor. It can kill opportunities, and it can kill success.” -Dwayne Johnson

But then the instructor said, “Actually, this student stayed true to an important rule in composite drawing, and that is to lose your artistic ego.” I perked up with this remark.

She went on to say, “Composite artists must only draw the memory being described. Resist the urge to pretty up your sketch. Lose your artistic ego.” With that, the instructor revealed the photo that the “witness” described to me.

Everyone in the class gasped, except me. I smiled.

Here’s the photo:

Needless to say, I passed the class and spent several years producing composite sketches of suspects. The artist in me always wanted to spruce up the drawings. But I remembered my lesson well. I had to let go of my artistic ego and just draw what I was told.

Some of my composite police sketches.

We all have egos. We want our work to be admired and valued by others. A little bit of ego is a good thing. It pushes us to achieve and improve. To care about what we produce.

But egos also get us in a lot of trouble. They can cause jealousy, frustration, negativity, and deep embarrassment. And it was embarrassment, I would learn, that was at the center of the young girl’s attempted kidnapping case.

They erode our strength

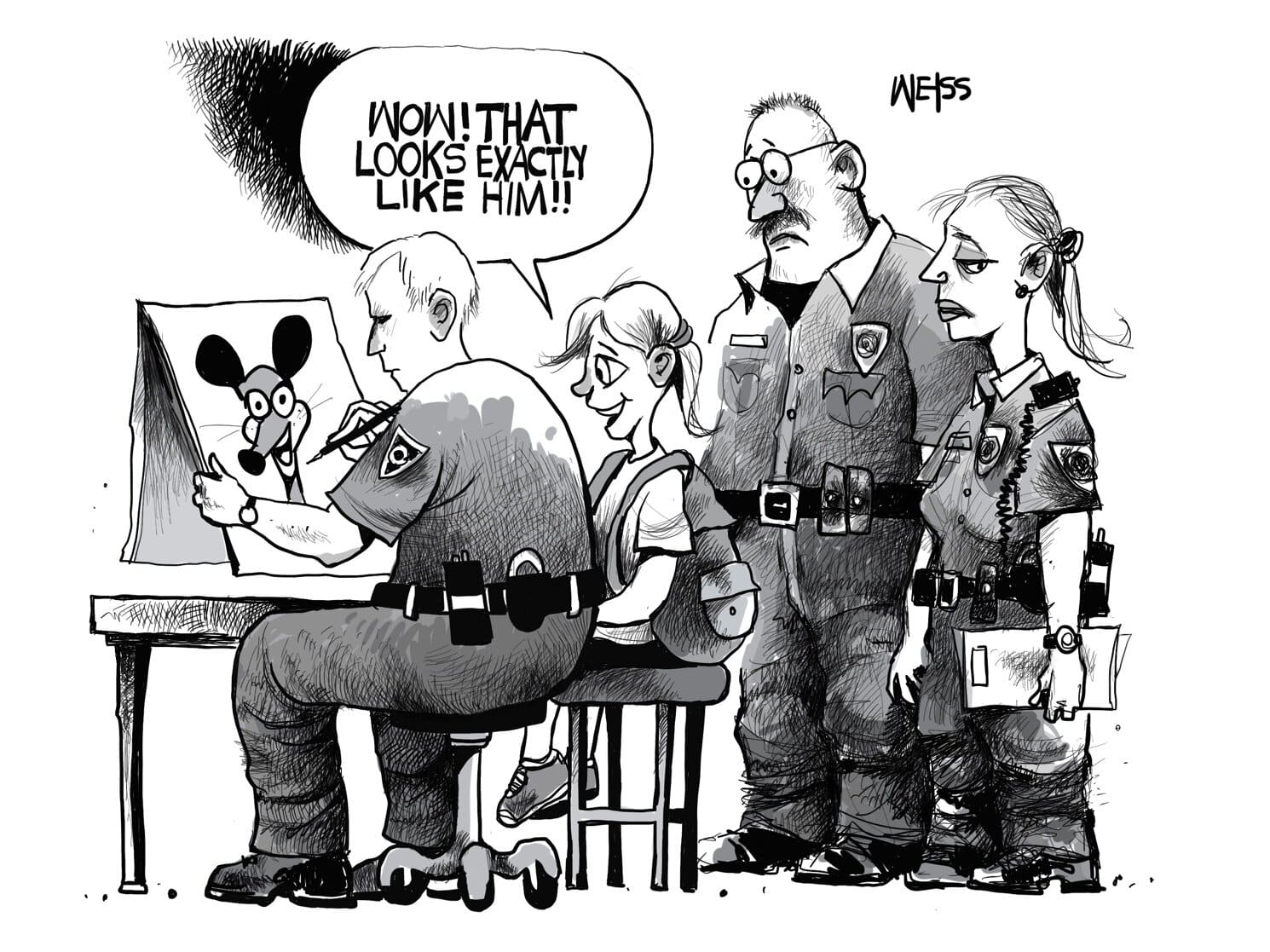

During my interview with the frightened girl, I asked some basic questions about the approximate age, race, and general appearance of the man in the van. Then I began the composite sketch.

She told me he had a round face and large nose, which I quickly rendered to her liking. Next, we focused on the eyes, which she described as “kind of squinty.” I drew the eyes and she immediately said, “Yes, that’s perfect.”

I asked about the lips and she said they were “average.” She added that the man had big teeth. I drew some exaggerated teeth and she exclaimed, “That’s perfect! It already looks like him.” With that, I sighed and put down my pencil.

“The truly scary thing about undiscovered lies is that they have a greater capacity to diminish us than exposed ones. They erode our strength, our self-esteem, our very foundation.” -Cheryl Hughes

Composite sketches usually require a lot of back and forth with the victim or witness. There are adjustments and corrections. And that was the problem. This sketch was too easy.

“You know, sometimes we make a mistake,” I told the girl, “and when we try to cover it up, it only makes things worse.” The girl stared at me silently.

“We all make mistakes. The key is to fix it, even if we’re scared or embarrassed,” I said. “Can you tell me what really happened this morning?” The girl’s eyes began welling up with tears.

Before long the girl confessed that the entire incident was a fabrication to cover up for being late for school. Her parents weren’t happy about the elaborate lie, but everyone breathed a sigh of relief. At least there was no kidnapper out there, preying on kids.

A magnet for enemies and errors

The experience with the young girl, and my subsequent years as a police sketch artist, taught me two things about people: Everybody has an ego, and everybody lies.

I know this is not an earth-shattering realization. But it’s largely true. Some people transcend these flaws, but most of us struggle with them.

When I was in composite art school, I wanted to draw amazing, detailed sketches. But composite art school is not about fine art portraiture.

A good composite sketch has one job, and that’s to capture a likeness of the suspect. It doesn’t have to be pretty, just accurate.

The composite art school instructor told us to “lose your artistic ego,” but the broader lesson is to lose your ego in life. The ego always has a way of getting us into trouble.

“Ego is the enemy of what you want and of what you have: Of mastering a craft. Of real creative insight. Of working well with others. Of building loyalty and support. Of longevity. Of repeating and retaining your success. It repulses advantages and opportunities. It’s a magnet for enemies and errors. It is Scylla and Charybdis.” -Ryan Holiday, Ego Is the Enemy

The girl who was late for school concocted an attempted kidnapping story to cover for her tardiness. Her ego didn’t want to face punishment for being late, so she lied. But lies have a way of snowballing, and soon she was in much bigger trouble.

As noted above, a little bit of ego can motivate us to improve ourselves and our work. But more often than not, our egos get us into trouble. And so do lies.

As a detective and police sketch artist, I saw a lot of people complicate their lives. Some ended up in jail or prison. All because of their egos and lies.

Egos and lies. Avoid these two flaws and your life will be better.