What is it to be a strong man? That, to butcher a famous soliloquy, is the question. It’s a topic that has been explored for generations, from the quill and ink of William Shakespeare to the digital pages of this humble website. And it’s the central theme of ‘Fat Ham’, a Pulitzer Prize-winning riff on ‘Hamlet’ that’s about to light up Broadway.

Marcel Spears stars as Juicy, who is described as “a kind of Hamlet” in playwright James Ijames’ brilliant script, and he shares many struggles with Shakespeare’s title character — not least the ghost of his dead father returning to demand that he avenge his murder. Like Hamlet, Juicy is grappling with his identity and how to live his most authentic life amid pressure to be something he’s not. But this time, our leading man is Black, gay, and battling to break from the toxic masculinity that is rife in his household.

Our new story is set at a barbecue cookout in present-day North Carolina, rather than a medieval Danish castle. But stuck in the dark ages is Juicy’s dead dad, Pap, and his uncle Rev — who is accused of killing his brother before quickly marrying his wife, the same dirty move pulled by King Hamlet’s brother Claudius in the 400-year-old original script. “You were powerful when you were a baby,” Rev says to Juicy, between gloating about marrying his mother. “Then you grew up a bit, and you were soft. You were nothing like your daddy or like me, you were soft. The men in our family ain’t soft and I started to think — look at this little pocket of nothing.” But amid the tragedy and dysfunction of Shakespearean proportions there’s also plenty of levity and laughs, and a sparkling, spectacular finale that I won’t spoil except to say it deserves a Broadway stage.

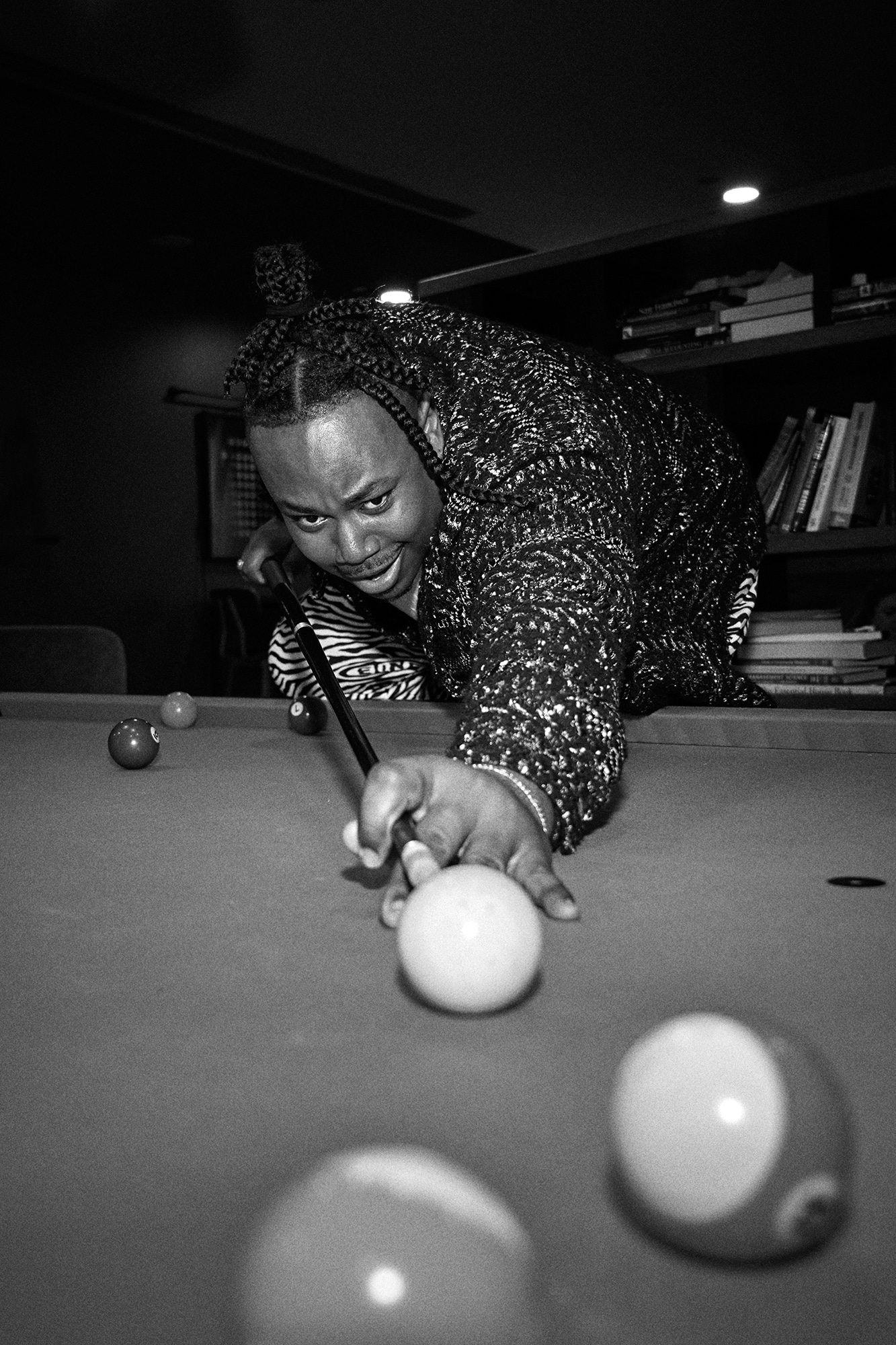

The script won a Pulitzer Prize in drama before it had even been performed to a live audience, and it enjoyed endless further deserved plaudits during its long sold-out run at New York’s Public Theater. It opens in its new home of the American Airlines Theater on April 12, where it becomes the first National Black Theatre production to transfer to Broadway. Here, Marcel — also star of hit CBS comedy ‘The Neighborhood’ — discusses the themes of masculinity and identity raised in the play, and how the evolution of attitudes is affecting both the younger and older generation. He also describes his relationship with Shakespeare, his own family, and why food is the soul of the South. ‘Fat Ham’ is fun, thought-provoking, and thoroughly delicious — please allow us to whet your appetite.

What are the similarities and differences between your upbringing and Juicy’s? I believe you were also brought up in the South, not too far from where ‘Fat Ham’ is set.

The play is set in the Carolinas, and I’m from New Orleans. My parents are both preachers and educators, and I grew up in a very unique city culturally; a melting pot of art, people, food, and all these different things. So that started to form my identity and who I am. Then I started acting more seriously after Hurricane Katrina [in 2005]. Our home was destroyed, and that pushed me and my family out of Louisiana and into Texas. I was 15 or 16, and was a fish out of water. I didn’t really know where I fitted in. So I focussed on theater and that proved to be a defining moment for me. Acting helped me to process a lot of the things I was going through as I was trying to figure out what life was in this new place and work through a lot of my shit.

The character Juicy, who is based on Hamlet, is a fish out of water as well. He’s a young, queer Black kid. He doesn’t really know if he should leave his family home or not, but home isn’t necessarily a safe place. So he’s trying to make sense of his world and define himself in a space where he feels confined. He doesn’t have the support to be his full self every day. And so that is proving to be a pressure cooker for him to figure out what’s going on. On top of that, his dad just passed away and his uncle has just married his mom, so it’s messy — like in ‘Hamlet’ — and he’s trying to figure it out.

I empathize with someone in his position. I grew up with a religious background, in a place where the idea of what a man was supposed to be was already pre-dictated for me. The script was written. And I played that role of a protector and provider really well. Then as I grew up, I had different experiences and met different kinds of people, and realized that some of those things weren’t helpful, and were actually harmful. I began to feel like the kind of man that I wanted to be shouldn’t be limited by the archetypal gender roles.

That’s what I took from this play and your role, that it examines how masculinity is changing. It’s something we talk about a lot on this site. How do you take the positive aspects of traditional masculinity — because we do want to be strong and protect our loved ones, and there’s nothing wrong with that — while also being more open to the other emotions and feelings that we all experience?

I feel like masculinity, and this idea of what a man is, has always been a mask anyway. All of the men I knew were playing a role of what they thought a man was supposed to be, but they also had all of these other elements. They had this deep wealth of vulnerability. And I feel like the moments that stick out to me between myself and the men in my family are the times when they are being softer, more vulnerable, more loving.

I feel like I’ve always had elements of that around me, but there was also this idea that a man is limited to strength and productivity. I still have this in the back of my mind. So I still feel like I’m only as valuable as what I can produce; I’m only as valuable as my ability to protect the people around me; I’m only as valuable as the amount of disrespect that I’m willing to tolerate in any given situation, and what my reaction will be. But, as I’m trying to unlearn those things, I’ve realized that’s not really the heart of what being a man is.

So what do you think the heart of being a man is?

I think the tenets are the same, but it’s the context in which we use them. Strength is wonderful, but there’s strength in vulnerability, there’s strength in restraint, there’s strength in your ability to love someone else fully and completely. Being a protector is great, but your ability to protect is not limited to the physical. How do you create a safe space in your home for your child to be able to come to you and say whatever they’re thinking? I feel like every man would want that for their children. I know I would. So I think those ideas of strength and protection — these masculine motifs that we put forward — are fine, but we have been limiting the scope of what they can be. There’s a lot more heart, love, and capacity for empathy within that.

Did you take that role within your family, that you were the one trying to progress some of these ideas of masculinity?

I would say so. It’s kind of a domino effect, each generation improves upon the last in some ways. The people raising me, Gen Xers, were some of the first ones in their family to get educated. These are people who are the product of the civil rights movement and the freedom fighting that came from that. These are the first kids that were able to start to benefit from a lot of those hard-won civil battles. So these Black kids grew up in a world where they saw more of themselves on TV, and started to have a bigger voice in the community around them. So then I come along, and I’m like, “Yeah, okay, that’s great. But also, we can improve.” I’m one of the first people in my family to go to therapy. Growing up as a pastor’s kid, therapy is church. Church is where you go to lay it out in the open. I don’t knock it, I think religion has its place. But I also think it’s important to talk to someone who has dedicated themselves to learning certain tools and techniques to help us unpack things that, especially as Black men, we just push down because we don’t feel like we have permission to feel them.

I love that you said you’re the first in your family to go to therapy. We often hear people being proud that they’re the first in their family to go to college, but we don’t hear that so much! The relationship between Juicy and his father— who is very dominant, puts him down, and uses fear to control him — is a dynamic I can recognize from fathers and sons in the era when I grew up. But I don’t think we see that dynamic as much anymore, I do think that the playbook for fatherhood has improved hugely.

Parents want what they believe is best for their kids, but you only have the tools that you have. I think my dad got it hard from his dad, and he made an active choice not to be that way with me. But from growing up in that environment, you still keep some of those things with you. This idea of being steadfast, unflappable, self-sufficient in a way that’s almost isolating, was embedded into who I was. My dad was always at work or church. In the case of Juicy, his father Pap is wrestling with the fact that he has a young, Black, gay child in the South. And Juicy is also visibly queer, visibly different, and his dad just sees it as a recipe for disaster for his son. He tries in the most unhealthy ways to get him to be someone he’s not so he can survive this world.

Tell us about your relationship with Shakespeare.

I got a theater degree in Texas then did my MFA [Master of Fine Arts] at Columbia University, so I’m classically trained. I worked a lot with Shakespeare’s material, and it was really valuable to play with those ideas and that language. But as a Black kid, it felt completely foreign to me at the start. I just felt like I wasn’t invited to that party, and when I was learning the material, I felt like I was almost being taught to be something I wasn’t. But the more you learn about Shakespeare, you realize he was writing for the people. The kings and queens would sit high above and watch, but then the regular people would watch from below and cheer and boo, and react very loudly to what was happening. He wrote to capture everyone from the nobility to the average Joe. And it has all these beautiful ideas — of grief, greed, joy, and rage — that are still relevant today. So my natural inclination was always to ground it in me and my experiences. Then fast forward to this play, our playwright James Ijames is doing exactly that. He’s taking Shakespeare, pulling it apart, unpacking it, blending the beautiful soliloquy with the language of people who talk shit like me. So when I read the play, I felt like it was written specifically for me.

Food also plays a central role in this play. And as Shakespeare’s banquets show, it has been connecting people for centuries. What was the role that food played in your home?

In the South, food is everything. Food is currency. Food is king. Especially in the Black community, and especially in the South where resources aren’t as plentiful, it’s seen as an act of love and sacrifice. You can’t throw a festival in New Orleans without food. You can’t have a meeting without food. We have food in church, we can’t even praise the Lord without eating. It’s so deeply embedded in the way we express who we are. And I think that’s universal. My favorite thing to do when I go to new places is try the food because that tells you a lot about who these people are.

Fat Ham won a Pulitzer Prize before it was even shown to the public. Tell me how that happened, and how it felt for you becoming a part of that.

James wrote this play in the pandemic, and with the theaters shut down, he recorded this filmed version of it just to get it out there. The script is just beautiful, how he weaves in Shakespeare and repurposes the language in such an intentional way. So while we were in rehearsal last year at The Public, and nobody had seen the show, he won the Pulitzer Prize for the script. Then it dawns on us that if this play is not well received then it’s because we suck, because the script has already proven itself. So we felt that pressure, but took up the mantle and think we did a great job. We got extended at The Public a gazillion times, and now we’re going to Broadway. It’s my Broadway debut, as it is for most of the cast, and the playwright, and our director [Saheem Ali]. It’s something I have always wanted, and now it’s here it almost doesn’t feel real. I’m taking it as an opportunity to tell the story as clearly as I can, so anyone who comes to see it can see themselves in it, and get something from it.

I think the artist’s job is to reflect the world around them and I think this play does in such a beautiful way. It allows people who are oftentimes forgotten the opportunity to be seen and heard on stage in a way that I think is healing. I think it gives us an opportunity to look at ourselves and reflect on some of the ideas that would lead to someone being put in this situation. This play is hilarious until it’s not, it’s sad and tragic until it’s not, and then there’s this great wave of joy and levity. And I think that ability to laugh at something that is really painful sometimes gives us access to healing.

Styling assistant Brittney King