Like millions of others, at the beginning of the pandemic I found my working life as an advertising photographer in Los Angeles suddenly stopped.

The experience felt similar to being in New York City on September 11, 2001. What had been important one day didn’t matter at all the next, as we learned the world was now confronted with a still to be understood, potentially deadly virus.

As I had in New York 20 years ago, I headed out with my camera. It’s my way of understanding life and the world, through a lens; if you can photograph it, it can be described. For a couple of weeks I photographed life on the street, so many people suddenly wearing masks, seeing the homeless whose situation, already dire, facing new difficulty and danger. And I started to read about the courageous people who were being conscripted to the front lines to fight the virus, the doctors and nurses.

I have a friend who is a doctor and her husband, Marcus Carty, is the sole physician at a group of Urgent Care clinics in the Coachella Valley, seeing up to 90 people each day and caring for an underserved community where one in five people live in poverty. I asked Marcus if I could photograph him and ask him about his experience in this moment. Marcus agreed, and then suggested I might want to speak to a good friend of his, another doctor.

Andrew Southam

And so it went, each doctor or nurse or social worker or citizen helping support people on the front lines of care and treatment for Covid-19 referred me to someone else they admired and knew was doing great, unheralded work. Marcus’ wife also reached out to a neighbor on my behalf, who had very recently lost her husband, a wonderful man who worked in an acute care nursing home devastated by 20 Covid deaths early in the pandemic, when the risk and danger the virus presented were not yet understood.

I drove over a thousand miles to spend time with these incredible people and make their portraits. The people I met were heroes, but none of them would ever describe themselves that way. Doctors and nurses and the other people I met who were supporting the effort to contain this virus in different ways spoke in clear, undramatic words. Doctors don’t tend to embellish their accounts with emotional language, the way most of us might when confronting death and serious illness. Some of them had been in the room when a patient had died in isolation, quarantined away from their loved ones, comforting terrified patients in their final moments.

I won’t ever forget their stories or their faces.

Dr Moazzum Bajwa is a physician and teacher at Riverside University Health Systems (RUHS) in Moreno Valley, California, the county hospital for Riverside County, covering a huge area of mostly underserved, vulnerable population from the eastern edge of Orange County, to the border of Arizona.

Dr Moazzum Bajwa // 📸: Andrew Southam

A question we all ask ourselves as physicians is how can I just mitigate the damage right here and right now to these patients? And that engenders a lot of anxiety, it makes you feel inadequate in the face of a pandemic. No matter how good your clinical skills are, you may not be able to help these particular patients. And I think that’s compounded by the abject isolation that these patients with Covid are dealing with.

When I would go into the rooms to see patients who are isolated with Covid, it might be just myself and the nurse are the only human contact a patient will have for a 24-hour period. And it’s such a different, harrowing level of isolation that you really can’t fathom. The patients are overjoyed to have human contact, but you can also see desperation in their eyes, of praying for some good news that you frankly may not have for them. They’re just waiting for some updates, waiting for some information. I may talk on the phone with them later on, or video chat, but it’s not the same thing. And that weighs on you so heavily.

It’s a dangerous game because when things go badly, as they inevitably do sometimes, we take that very, very personally. I can say unequivocally the most down and depressed I’ve felt as a clinician was during the first week I was taking care of Covid patients. Not because the work was so demanding or because I was doing so many crazy things, but really just because I was feeling very isolated and seeing how lonely those patients were made me feel like there was nothing I could do to fix that situation. And I felt a ton of despair.

But what I realized was that the more that I could actually focus in on my little world, and the community in which I exist and the work I’m passionate about, I felt much more hopeful and confident about what we could do. And then seeing the beautiful community response that came out in so many ways to the initial onset of the pandemic, and just watching how my neighborhood has responded in positive ways, it’s allowed me to re-center and say, “Okay, well, here’s what I can control, here’s what I can do. And this is my impact,” instead of focusing on all the things that I can’t control.

Mark Hyk succumbed to Covid-19 in May last year, after a heroic 38-day fight on a ventilator. 66 years old, energetic and in great health before his illness, he was a former firefighter who was working as an occupational therapist at an acute care nursing home facility when he contracted the disease. The day he became ill, the facility had its first Covid death, and it would go on to have 20 deaths and become the early epicenter of the outbreak in San Bernardino County. Mark’s wife Carol Bunz tells his story.

Carol Bunz // 📸: Andrew Southam

“Mark loved helping people, patients, family and friends. He’s the guy that ran into burning buildings to save people. He’s the frontline healthcare worker that you read about. He’d come home sharing success stories, what his patient had gone through, what they had to overcome to be able to get back home.

“Mark would say, “I believe in the power of rehab!” He was looking after his patients when he got sick, that’s who he was. He took care of his family and mine too. He loved his daughter, grandkids, sisters, nephew, grandnieces and nephews, my sons, grandchildren and great grandchildren. He made all of them his own, and they loved him in return.

“The hardest thing was not being there with him. Had he fallen ill three months earlier, I would have been there with him, holding his hand, talking to him and trying to help him through it. After one month, I was allowed to see him for just an hour, and afterwards he rallied. He had the strength and fight. I just kept on praying.

“I can’t say enough about the medical people who tried so many different things. The virus just went on a rampage through his body. I feel that for the frontline healthcare workers who went like Mark, there should be some acknowledgement. They’re the unsung heroes.

“I can’t do a memorial now. I’ll take Mark’s ashes to Rochester to be by his parents, that was what he wanted. I have had wonderful loving support from family, friends and neighbors. I just take one day at a time now. The hard part for me is I miss him so much.”

Born in Zambia, Dr Madalitso Chundu is an internal medicine physician at Loma Linda University Hospital, California, and assistant professor in the school of medicine. He was diagnosed with Covid-19 after attending patients in the ER, and rounding on the coronavirus isolation floor.

Dr Madalitso Chundo // 📸: Andrew Southam

“I came down with symptoms on April 3, 2020, feeling tiredness like having run a marathon, when I’d just woken up. After day one, I didn’t need testing to confirm the virus. Then I began occupational health processes our hospital manages work-related exposures with, involving multiple nasal swabs and serology until I tested negative for the virus and was safe to return to clinical duty.

“Getting ill, it’s struck me how unfairly this virus has affected society. Most of the people getting sick where I work are from long-term nursing facilities. The most disadvantaged by disease, age or economics are bearing the heaviest burden of suffering and death.

“I had one patient, a 50-year-old man who came into the hospital a week before I got sick. He came into the ER with an unrelated medical issue, but screened positive from exposure to the infection at his nursing facility. On the second day he developed respiratory symptoms, becoming very confrontational with the staff. He’d been polite the first day and when I talked to him he said, “I came from a nursing facility and the night before I came in two people around me were drowning in their own lung’s fluids. I’m scared that since you guys are starting to give me oxygen, it means I’m going to die and I can’t speak to my family or have anyone next to me.”

“Unfortunately, his words proved to be true. By the time I left that day, he required so much oxygen he was intubated. He developed acute respiratory distress syndrome, the lungs fill with fluid and scar down making it hard to breath, and he did not survive. And that’s just one of many stories of people succumbing to this virus.

“When I contracted the virus, I wasn’t shocked. I knew roughly what the arc of my illness would look like. There was a moment where I thought, “Maybe I won’t make it through this.” But, never at any point did I second guess my choices. Like most other medical professionals, I feel this job is a calling. In fact, this has reminded me my job is to be there for people in their moments of illness. It’s reinforced for me why I chose to be in medicine.”

When the coronavirus pandemic first took hold, Dr Marcus Carty was the sole physician assigned to a group of Urgent Care clinics in the Coachella Valley. I photographed Marcus with his son Dean. Many of the frontline healthcare providers have families that, though they take every precaution, they put at some risk, in order to do the work they do. Marcus’s wife, Melissa, also a doctor, is six months pregnant with their next child.

Dr Marcus Carty and son Dean // 📸: Andrew Southam

“Once the pandemic really hit initially, it was chaotic because there weren’t policies in place. We were making up our own rules on what to do with patients with guidance still emerging: How many people we could have in the clinic at one time? To screen outside or inside? What questions to ask? Because the urgent care wasn’t set up for this, we were scrambling to figure out what to do. Scrambling to find proper protective gear.

“Multiple people I saw were in the healthcare field, nurses and nursing assistants. Some of these people were working in emergency rooms where their absence would be greatly missed. And these sorts of things were life altering for other people; people who might not have their unemployment claims processed for a month or longer if they had to stop working. We’re talking about a very underserved community that I’m supposed to be protecting. And were they not going to be able to pay their bills, or afford groceries, because of a decision I had to make?

“Where my family and I live, a lot of people are angry about their rights, about being told to stay at home or wear a mask. There’ve been protests for reopening, celebrations when a store is reopened. Meanwhile, our neighbor’s husband and our friend’s family member just died of Covid last week, and they must cope with the reality that there wont be a funeral or community to support them. I worry if people aren’t directly affected, it isn’t real to them. They’re just sick of being restricted.”

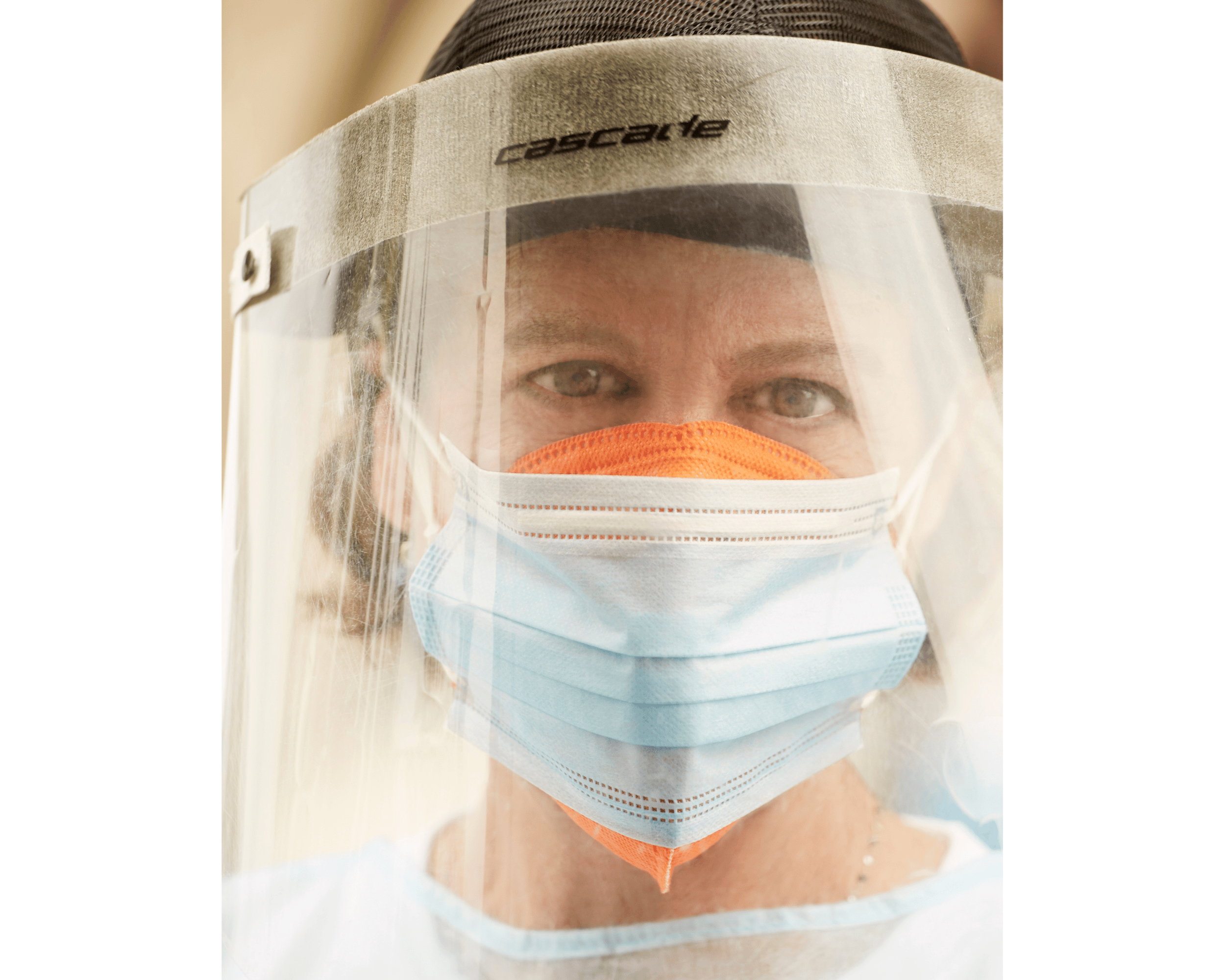

Over and over while I was working on my Frontline Portraits project, doctors have told me I should be talking to nurses, that they’re the front of the frontline. Charee Stewart is a nurse coordinator for the County of Riverside. She’s been a registered nurse for nearly 14 years, and prior to that she worked in healthcare for over 10 years. If I were ever to be critically ill, hers is the face I would hope to see.

Nurse Charee Stewart // 📸: Andrew Southam

“A consistent observation among many disciplines is how Covid-19 has forced us to change how we communicate. Healthcare workers experience sensitive encounters daily. To connect and express empathy is paramount to the best experience and outcome for the patient. But to protect everyone, the wearing of face masks as a society is imperative. The trade off now is sometimes the inability to interpret facial expressions, which are the foundation of how we convey feelings and understand interactions with others.

“In terms of visitation, Covid-19 is a highly contagious disease with the ability to spread rapidly and lead to deadly outcomes. A person can have Covid-19 with zero to very mild symptoms and unknowingly spread it to others. Critically ill patients with chronic medical conditions are the most vulnerable and a large percentage of those presented to us for care. Many facilities have restricted visitation to virtual meetings, phone or video in many instances. But we also know the support of patients’ families is equally important. To hear their voices and be physically comforted is a vital piece to a patient’s care and outcomes. Research shows that patients experience better outcomes when touch and family support is factored. They’re just as important as any medicine we can offer.

“So loss of connection has really affected healthcare for us all on an emotional level as well.”

Annie McGuire is an executive producer who lives in Palm Springs, California. She normally works in the world of events, and when that world shut down she found a way to play her role in the battle against the disease at a testing facility.

Annie McGuire // 📸: Andrew Southam

“I had a full work calendar, traveling internationally through October 2020, and then everything was just postponed or cancelled. So I spent most of March and April watching all the pain; loss of life, of human connection, feeling uncertainty about my future, and anguish about our federal ‘leaders’ heartless negligence.

“I numbed myself on Netflix for a while, but one day felt I needed to help somehow. I researched Covid-19 volunteer groups and found CORE, created during the Haiti earthquake. They provided support on the ground in the Bahamas after the 2019 hurricane and continue to regroup in times of emergency.

“I was assigned to the VA Center testing site in Santa Monica. The first day was an orientation for supervising testing and how important it is to give directions as clearly and gently as possible, as people coming in for testing are often nervous. There are different positions on the team; directing traffic, scanning and handing people their test kits. We stand outside their car and walk them through it. Because we supervise a self-test, we don’t have doctors and nurses on site, although we have police officers and EMT’s, in case someone gets a little aggressive or agitated. One person, instead of following directions just took the test tube of solution and drank it so the EMT had to escort them to the hospital.

“CORE keeps us very safe with PPE, and separation from the test subjects. We wear a long gauze cover up and an N95 mask, a regular surgical mask over that, then a space shield on top of that, and have gloves on. The work is voluntary. CORE provides us with a number of therapy sessions, in case we have anxiety or depression during this crazy time. I had my first session yesterday and I’m going to continue.

“The test is free, provided by LA County. About 1,500 cars come through a day. After I took one guy’s test, he held up a sign that said, “Thank you, Hero”, with colorful hearts around it. I almost started crying. People are very grateful we’re here. It makes me feel I’m making a difference.”

Dr Nikki Mittal specializes in pulmonary and critical care at Riverside University Health Systems. She lives with her husband and five year old son. I talked to Nikki last July about how she handles end of life discussions when people can’t easily visit family. Her colleagues say she has a gift for handling this impossible moment with great care and respect for patients and family. Nikki and her team are also treating inmates from the local big jail outbreaks.

Dr Nikki Mittal // 📸: Andrew Southam

“At the beginning of the pandemic I took charge of Covid response in ICU. When things started going crazy in Italy I went to my group’s head, because a lot of our critical care research comes from Italy, it’s a very advanced medical system.

“If they’re overwhelmed by Covid deaths, that’s very worrisome. I said, “I’m putting plans in place or I’ll have a nervous breakdown. I can’t handle knowing it’s coming and sit here unprepared. How are we going to separate patients? What to do to build teams to respond?”

“Patient’s families trust you less when they can’t meet you. They don’t see how much care we give their family member.“ Last week in ICU six people died, a few quite young. We’re calling family to say, “Now they’re dying you can come in, let me get approval from admin so you can visit.” It’s so hard to have this conversation on the phone, not in person where they can feel your compassion. I had classes in med school but really I learned in residency, sitting in on every family meeting I could. You see a lot of really bad ways to do it and a lot of amazing ways, you pick up the sprinkles. I try to make that transition a little bit easier for the family.

Division Chief for the largest division in the department of medicine at Loma Linda University Medical Center, Dr Michael Matus administrates 38 internists, who have borne the full impact of the Covid-19 patients there. I spoke to Michael last June, in the relatively early days of managing his hospital through the disease.

Dr Michael Matus // 📸: Andrew Southam

“Prior to the pandemic, half my work was administrative, half was doctoring; providing patient care. Since the pandemic began, administrative time has gone to nearly all day, in addition to caring for patients, sometimes 14 to 16 hour days.

“The middle to end of March 2020 was far worse. I’d see patients, then run to a meeting to figure out how we’re going to allocate our N95 masks, who and how are we screening for testing? We had our first in hospital exposure to Covid-19. We then had to perform tracing determining who saw the patient. Initial estimates were 50 people. Is anybody symptomatic? Do they get pulled from service? It’s hard to overstate just how destructive an exposure is in the hospital. The nurses, nurse aids, kitchen, respiratory therapists, residents, the physician, consultants, all those people are potentially infected. And we have to move on that immediately.

“In terms of containment, I tend to see the glass half full. My professional assessment is I’m still quite concerned. The level of infectiousness of this virus is impressive. When you consider in just one day how bad a focal outbreak could be, leading to another surge at the hospital.

“The nervousness and anxiety the public feels, physicians and healthcare providers are not without that. Often that sentiment is shared by health care providers. I’m seeing patients, going into their room, examining them. I’m wearing all the gear, but consultants are very nervous that they’re going to get Covid as well. It’s very hard to get patients appropriate care, if they need an ultrasound, a CT scan, if psychiatry needs to see them.

“Patients are still getting sick with other diseases, we’re kicking the can down the road. But it’s been more than two months and we’re adapting. With appropriate testing we can get back to helping people.”

Dr Leanna Wonoprabowo is a family and preventative medicine resident and part of a close-knit family with Chinese and Indonesian parents. I photographed her from the front yard of her house in Redlands, California, through her front window, before she headed to work at Loma Linda University Medical Center.

Dr Leanna Wonoprabowo // 📸: Andrew Southam

“I was actually scheduled to be in the emergency department from a year ago and it just happened to be at this time.

“In the ED, it’s a little more tense. There’s an air of uncertainty. People are very concerned for each other’s safety. That was the case before, but it’s even more so now, like making sure that everybody’s covered in terms of protective gear.

“This has been hard on my parents and I know they are scared on my behalf, even though I feel like I should be more scared for them, given their age and history. That’s one of the hardest things for me during this time. I’ve chosen not to spend time with them since it all started because I don’t want to potentially risk passing it to them if I was a carrier.

“But all of this has made me think about our patients more. Many of my patients in San Bernardino have a lot of socioeconomic difficulties. They have a lot of uncertainties at baseline, and a lot of them struggle so much with anxiety because of it. And to think how anxious this one uncertainty has made me has definitely given me more empathy when talking with my patients.

“I think one of the things that I’ve seen that frustrates a lot of people in healthcare is we sense an indifference to the situation by some of the public when they are not personally affected. That’s a little bit hurtful to people on the front lines.”

Kristee Benedetto is the emergency and ICU social worker at California Hospital Medical Center, in Los Angeles. She lives with her husband, 15-year-old daughter and 10-year-old son.

Kristee Benedetto // 📸: Andrew Southam

“Once a patient is identified as Covid positive, if they’re in the emergency room, I can talk to them on the phone, but I can’t go bedside. There are no bedside assessments. In ICU, I’m unable to speak with the patients directly because they’re either on a ventilator or they have a high flow mask on, so they’re not able to speak to me. So all of my interactions are really with the family members.

“That’s where I feel really useless because I don’t have a lot of resources for people who now don’t have paychecks. I give them information on food banks, I make sure they know how to get their stimulus check, but there’s not a whole lot more I can do.

“I do help facilitate accommodation in collaboration with the Department of Public Health if a patient comes into the emergency room with mild symptoms and they need quarantine and isolation, and can’t isolate at home safely. I had a situation with a husband who had a baby with health needs. His wife was in hospital and he couldn’t afford the hotel any longer. He didn’t know anything about the quarantine and isolation housing, and couldn’t go home because there were too many people for him to isolate and keep the baby safe. I was able to get him into quarantine housing for him and the baby. Two days later I found out his wife had died. So yes, we got him to a safe place, but then there’s a loss that can’t be mended.

“I’ve worked in a variety of healthcare positions, from hospice to ER to ICU to oncology. There’s a sense of desperation and overwhelming sadness that I feel now, because there’s no rhyme or reason to any of this. I’ve had at least 10 patients who died of coronavirus. I had interactions with their family members that were very emotional and desperate.

“I’ve talked to my kids about what’s happening. My daughter is worried about me emotionally, and my son’s more worried about me physically, he doesn’t want me to get sick. I don’t think I’ve really been able to reassure my daughter because there are days that, at the end of the day, I just can’t anymore. I come home and shower right away and I cry, and some days I just get into bed and I’m done. I’m feeling emotionally drained and that I really don’t have much to offer these families on the other end of the phone except my voice, and to normalize their feelings and their fears and try to have them feel heard and supported. But none of that is concrete and tangible.”

Chris Sey, a screenwriter, married to an ER doctor, joined with friends to launch Dine11 and provide meals for healthcare workers and support imperiled local restaurants.

Chris Sey // 📸: Andrew Southam

“My wife, on the frontline as an ER physician, became sick with every Covid symptom imaginable except needing to be hospitalized. When Rachel went back to work the atmosphere in her cohort was anxious, very worried they were about to see a huge influx of patients, and didn’t know what they were dealing with. Just a ton of uncertainty.

“Her superiors at Cedars asked her to lead a mental health initiative, addressing what doctors and nurses themselves might be dealing with. We kept returning to morale. How do you keep morale up in an emergency department? Once the pandemic hits, how do you do it? How do you keep staff feeling safe and appreciated?

“I sent an email to six people I felt like knew other people, in manufacturing, movers and shakers. It began as a mask drive. In the process I talked to my partner in crime, one of the principals in Dine11, Lola Glaudini. She said, “Why don’t we raise some money to send the ED at Cedars a meal?”

“We called every restauranteur we knew. They all said, “Yeah, we’d love to do whatever we can.” Lola recruited Judy Han, a chef with a long history in restaurant management, she knew everybody in town. We started recruiting money, restaurants, volunteer drivers and people to help. In three weeks, we raised about $40,000 to push back into the restaurants. We joined a nonprofit, March On, so donations are tax deductible. So far we’ve raised about $250,000, and sent out about 20,000 meals. We’ve helped save between 800 and a 1000 restaurant jobs. We realized a week into it that the physicians and nurses didn’t have food at the hospitals. We were able to make things a little bit more convenient for them.

“The whole experience has been profound for me. Service is a really positive lesson to learn. It improves your own life.”

LA restaurant veteran Judy Han is another of the people behind Dine11, getting meals to frontline caregivers and supporting local restaurants. When we met last year, Dine11 were in plans to feed organizers of Black Lives Matter protests, and provided meals for 200 people on the protest team from black owned business Post & Beam. As Judy described it, “A double win!”

Judy Han // 📸: Andrew Southam

“When Covid hit, I texted “How can I help?” I took over logistics and became restaurant contact, working with the hospital contact to set up catering, coordinate restaurants, get them paid and decide timing. At our peak we were doing 12 or more deliveries a day.

“The restaurant industry is where my heart is. Chefs and owners are a particular breed. When times get tough we try to be there for each other.

“When protests started and it became violent, Josef Centeno posted photos of his restaurants windows broken and graffitied. I realized it was serious. I contacted all the restaurants and even if they suffered damage, they all still wanted to do it. Then one of the core members of Dine11 met organizers of Black Lives Matter, can we divert some food to them? It’s a protest, and a lot happens in secret, but now protests have become more peaceful we’re working it out.

“We’re in a strange time. A lot of very skilled people aren’t working, want to work or do something productive. I can’t think of a single person who doesn’t feel the same way; we don’t support rioting, but we support the protest. We’re going to try to at least feed them.

“It’s amazing how people have responded. Josef, and Nancy Silverton from Mozzas restaurants, were ransacked and burned. But even if they suffered from rioting, restaurant owners feel the protests are absolutely necessary.

“The protests are not surprising, a lot of people don’t have much to lose. When it was just Covid, something was brewing because of joblessness and insecurity about the future. Now it’s an idea we can latch onto, a cultural change for us to focus on. Of how and what ways we can change.”

Dr Daniel Patton is an orthopedic surgeon and assistant professor of orthopedics at Loma Linda University, California. In February he replaced the ankle bone of a patient, damaged beyond healing in a car accident, with a new bone created with 3D printing, allowing the man to walk without pain within two months. He’s also a trail bike enthusiast.

Dr Dan Patton // 📸: Andrew Southam

“Since this pandemic began, I haven’t had a day off. I recognize that in the current economic environment, to have work is truly a blessing. Many people currently are out of work and with more free time comes the ability to hurt yourself.

“What I do at work has massively shifted. With this pandemic, my focus has shifted to very time sensitive surgeries such as broken bones and open wounds. If someone breaks their leg and the bone is sticking out, we can’t wait for the pandemic to clear.

“This pandemic is absolutely something to be respected. I think that life as normal will be shifted; it will be changed. My wife and I have been personally touched by it. One of our neighbor’s husband died last night after six weeks of battling this. My wife’s godfather died two days ago after six weeks of battling with complication of Covid-19.

“That being said, we need to continue on with life in a new, safe way. Figuring out how to do that appropriately requires a fluid approach.

“I’m going to take care of patients as a calculated risk, no matter what. I was in Haiti a month after the earthquake hit in 2008 and experienced several aftershocks while I was working in the hospital. And I feel that this is the same environment. This challenge is not as physically tangible as a crumbling hospital in an earthquake ridden part of the world, but it is just as real.

“I’m going to take care of patients even though it does come at a personal risk and risk to my family. Taking appropriate precautions and caring for my patients, that is what I took an oath to do.

Dr Rachel Pearl is an ER physician at Cedar Sinai, Los Angeles, practicing for 20 years. She lives with her husband, and three sons.

Dr Rachel Pearl // 📸: Andrew Southam

“At the very beginning of the pandemic, I became ill myself for four weeks. It gave me opportunity to get my arms around this, support my colleagues, and learn about the disease. Frankly it was terrifying at times. Before I got sick, I cared for very sick people, I knew what that looked like. I knew the disease didn’t manifest worst state until a week into symptoms. The first week was a lot of anxiety, insomnia, meditation, and just working through thoughts about mortality.

“I try to see the positive. This is an opportunity for us to look within to find solutions to this that are sustainable and healthy for us and the planet in the long run. I find it stressful and I’m sad for the massive toll it’s taking, especially on marginalized people I have a fondness for taking care of. The homeless, economically challenged, developmentally, physically impaired folks with chronic illness, immigrants, illegal immigrants without resources many of us have. Psychiatric populations are high risk. Groups we in the ED are accustomed to advocating for and taking care of. Those people will be most severely affected. It’s hard to know that that’s inevitable, there’s still a lot of devastation coming. I don’t fear as much for myself, my family, or friends.

“I’m interested in end of life care, and death. This is an opportunity to address goals of care, for patients who haven’t wanted to think about or discuss those things with their physicians. At the beginning of the pandemic it was a discussion at the hospital, when we thought we were going to have a flood of patients and would have to decide who was going to get ventilators or be resuscitated. What if someone is very ill, needs to intubation or CPR, but is at end of life already, when you’re not quite sure what you’re fighting for, if quality of life can’t be improved, but you’re exposing multiple people to a potentially lethal illness.

“It’s an opportunity now to become aware of our own mortality and what we want our lives to look like. It’s an opportunity to live your life if you want to have a good death.”