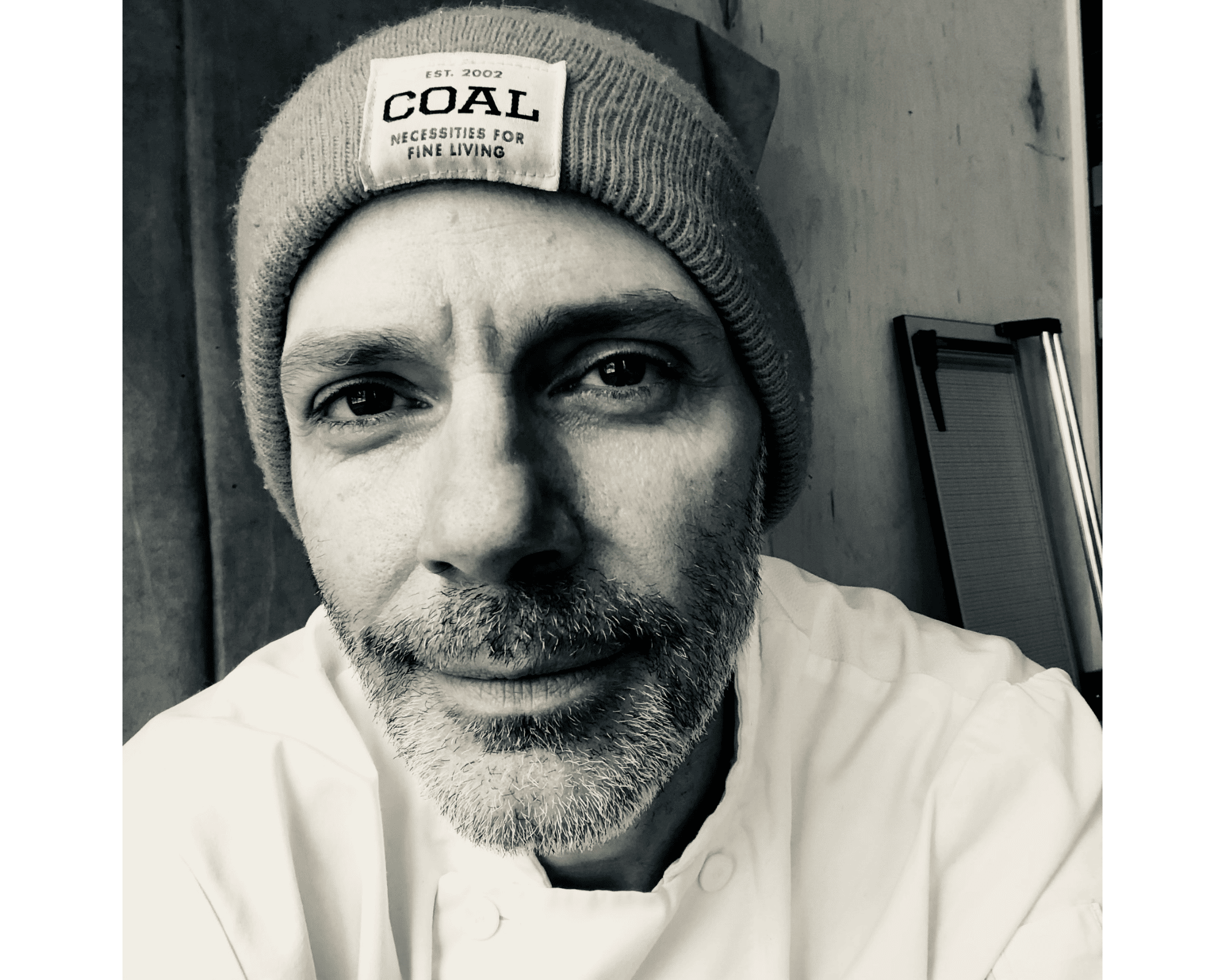

What possesses one of the most successful photographers of his generation to upturn his life, leave the status, paychecks and most of his possessions behind, and become a baker?

We pose this question to Norman Jean Roy, renowned for his iconic covers of magazines including Vanity Fair, Harper’s Bazaar and Rolling Stone, who walked away from a life littered with celebrity and glamour to go back to basics and open his own bakery, Breadfolks, in Hudson, New York.

After a period of soul searching and discomfort with his former career, Norman made the decision to open the community bakery just over two years ago. He spent seven weeks in San Francisco, California, training for his new craft, before opening Breadfolks in August last year, in the midst of the coronavirus pandemic.

It was a brave leap as he and his wife Jojo sought a simpler yet more fulfilling path, also giving up most of their possessions and embracing a life of minimalism in order to start afresh.

Here, Norman talks about his beliefs, courage and all that drives him to succeed, whether holding a roll of film or a rolling pin, in a thoughtful conversation with our co-founder John Pearson and head of creative Alison Edmond, that has lessons for us all in how to manifest change in our lives.

Breadfolks produce // 📸: Norman Jean Roy

ALISON:

So, how is it getting up at 4:30 in the morning?!

NORMAN:

You know, you kind of get used to that. Life is easy when you surrender to whatever it is that you’re in. I made this bed, I’m sleeping in it. It’s amazing. We’re kind of overwhelmed with the response that we’ve been getting. It’s still that ‘I can’t believe this is working’ kind of thing. Working, let alone working the way it is. It’s wild.

JOHN:

When did you realize that you wanted to become a baker? How did that come to you?

NORMAN:

I’ve always loved bread and flour and had this deep connection to the earth, and the soil, and what grows from that. I don’t know why but I have this real connection with flour.

Jojo and I had long discussed, the way that most couples do, “One day, when we’re older and we’re not doing this anymore, wouldn’t it be nice to…” And, because I love anything that’s bread and coffee (anyone who knows me can attest to this), wouldn’t it be so much fun, one day, to just be a baker and have a small café kind of thing, you know, in a small town?

I started going through this in my mid 40s. My agent at the time and I worked together for 15 years, and the entire time I struggled with the waste of my industry. I would get offered these sometimes ridiculous fees and I would think, “We cannot ask for that kind of money. No one is worth this.” He would respond by saying, “this is what the client offered to pay.” At some point I got to this place where it was just gross, and I wanted to find some sort of natural transition.

Breadfolks bakery in Hudson, New York

I spent two introspective years, consumed largely by a search for some way to square these feelings. Ultimately, the missing component in the whole equation was that my transaction with the person consuming the visual object that I was creating was never who I was personally engaged with. I was always one, two, three, steps removed from that intimacy. I was always longing for what I call a “closed loop transaction.”

So now, I create something where you pay me, you take it, you consume it, we’re done. The thing that’s different about this current state, something I’ve never had in my entire life, is a fixed schedule. We open at 10am. It has to be 10am. I don’t change the call time. I don’t move the shoot day one day. It doesn’t get canceled and shoot two weeks later. I don’t get to book myself out. You know, it’s all that stuff, those days are over for me. It’s very humbling.

I have worked hard in my life, but it pales in comparison to how hard I work now. We are, by any stretch of the imagination, a very successful bakery. If I can walk away with $150,000 a year in profits, I would be grateful. But we’re talking about thousands of hours to make that with no guarantee. In the past, that would have been one shoot day for me.

That welcomed contrast is profoundly humbling and deeply grounding. It beats you down to a place where you find yourself again. There’s no veneer to hide behind, no ego to protect.

At the beginning I was getting up at four in the morning, and I’d be in the bakery at 4:30, and I’d be there until seven at night. The first six months were brutal. As a matter of fact, the first month, I had many moments of, ‘What have I done?’

But then you have two days of rest, get back at it, and you’re fine. Then, you find your staff and it starts to click. Now I have five bakers and me, and another five people in front of the house.

I’ve been approached by several investors to open many more locations. What I recognize through this process is my curatorial talent for creating an experience. Breadfolks is more than a bakery, it’s an experience.

We’ve had people ask us to ship bread all over the world. All of a sudden, we realize we could open 20 or 30 locations.

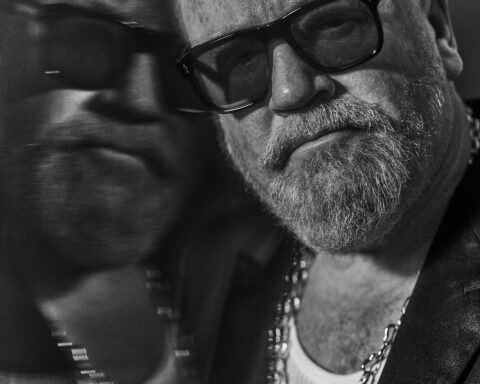

Vanity Fair Hollywood cover // 📸: Norman Jean Roy

JOHN:

You strike me as someone who is, in the best sense of the expression, a control freak. You want it all to be meticulously done because you’re a curator. Wouldn’t that take away from you being the guy who’s actually getting up, and working with your fellow bakers every morning, and supporting your community?

NORMAN:

No, not for me, because part of the love of doing this is the bringing people together. The reason it’s called Breadfolks, and not Breadfolk, is that it’s not about me. I just one of them. I am just a conductor moving an orchestra. You don’t go see the London Philharmonic only because of its conductor. You go because it’s the London Philharmonic. The conductor is there to organize the auditory experience.

Before, as a Norman Jean Roy entity, I had to protect and preserve that ‘brand.’ Your name is front and center.

Breadfolks is not. I can walk away from Breadfolks tomorrow and it can be it’s own thing. That’s the difference. It’s not Norman Jean Roy bread.

The freedom you have when something is not attached to your own name is something I’ve been relishing. There’s a great degree of anonymity provided that’s been absent in the past. On top of the fact that everything that we make gets eaten. And if we don’t sell out, the few pieces that we have left are donate.

And because we’re dealing with sourdough products to begin with, I’ve had to surrender control. There’s a living organism that’s going to do what it wants to do.

Norman with his artist wife Jojo // 📸: Will & Susan Brinson

JOHN:

It seems like you’re a man who has very few doubts, and is really here living his life, moment to moment. Knowing that you want to get the best out of every single moment, and at the same time giving everything of yourself to that moment. How do you feel about that?

NORMAN:

For me, you get up everyday and you look out at the hand you’re given. How do you want to spend that time? I don’t dwell much on the past. To me, memories have a magical way of carrying the experience with you. I always feel really sorry for people who try to hang on to an idea that they fabricated. It gets very confusing, quickly.

We all fall prey to that. I try and check myself often when I start becoming married to an idea. That’s when I find mechanisms to destroy it, to remove it completely, so this way I’m no longer bound by its tethers.

For me, inside that space is where it begins.

For many, many years, I struggled with the industry as a whole. I tried to find path that aligned with who I am rather than the idea of what I had be. And I just couldn’t, I could never square it for myself. So one day, we said “F*** it.” We literally got rid of everything, sold our house and most of our possessions. We sold almost everything we had for the purpose of removing ourselves from the attachments that came with that sort of lifestyle. We got rid of all our watches, luxuries and donated all my suits, tuxedos, shoes. Everything. And all I have now is s****y jeans and t-shirts.

Behind the scenes at Breadfolks // 📸: Norman Jean Roy

JOHN:

You still have your cameras, right?

NORMAN:

I got rid of most of my cameras. I shredded 75% of my negative archive. For me, it was never about accolades, money, or anything like that. All those things were just instruments that allowed me to go where I wanted to go with the medium. I never cared. If the accolades opened the door for me to enter into a place I wanted, I used it as such. But for my own personal satisfaction, any sort of recognition or validation is inert. It has never, nor will it ever will have any influence or weight on my own self-worth.

I live at my happiest when I’m completely invisible and I can just observe. Photography was always a mechanism to observe in that sort of way. But when the creator was bigger than the instrument, it became hard to live up to the myth. You start to create armors and protections.

To me, I was always using photography as a means to leave markers on my timeline so that I could, at some point, connect the dots and try to make sense of it all. So that period was just that, basically going through every single image I ever took — and we’re talking about millions of images. It was, at the time, very overwhelming because there was just so much content. Not overwhelming, emotionally, but overwhelming with the quantity of visual content attacking you!

When you no longer have to show examples of your work for the purpose of getting more of that type of work so that you can make money, it’s pretty obvious what’s good, what stays and what doesn’t. There were entire sessions that literally got erased from my archives, all together. Never to be seen again. Like the shoot never existed. That was deeply cathartic.

Breadfolks and Clayfolks produce // 📸: Norman Jean Roy

ALISON:

Was going through your archives the catalyst of really knowing it was time to say goodbye to this?

NORMAN:

It was trying to make sense of why I started doing it to begin with, what it meant to me today, and why I was still doing it. You really become very married to an idea of what and who you think you are.

There’s no question, my love for photography is intact. That never went away. I did two shoots last year and both times, I did it more out of curiosity. I just dipped my feet to see if I still had it. It would be like saying, “Can I still use my hands?” Of course you can use your hands! There’s a fluency to that language for me, an ease in the movement.

But over the last decade, we have been consuming visual content in these bite size morsels of information, reduced from their original formats. And that, by the way, includes me. I don’t look at magazines. I don’t read them. That sort of disposability is not what I signed up for.

L, Nicole Kidman for Harper’s Bazaar; R, Chadwick Boseman for Rolling Stone // 📸: Norman Jean Roy

JOHN:

How do you feel this change has helped your mental health? Your wellness? Your sense of self? You’re a part of this sort of ecosystem now, this community that comes to you. How does it make you feel?

NORMAN:

Well, I don’t think it makes me feel anything. For me, everything that you see, and feel, and observe is just a perception, right? You can change on a dime how you feel about anything. It’s just a perception that is informed by your own historical context. So you basically inform the moments that come in your life through that lens.

The older I get, the more neutral I become about everything. I don’t think that I feel great or not about anything, other than I feel more aligned.

You’re always where you’re supposed to be, regardless of what you think is happening in your life. When you realize that is when you become an instrument of change in your life.

Norman Jean Roy // 📸: Will & Susan Brinson

JOHN:

You were extremely respected in your occupation, and you just acted on a life change midway through life. What advice would you give to people who possibly aren’t as fearless, who perhaps don’t have the clarity or the perspective, energy, chutzpah to do it?

NORMAN:

I’ve lived my life by this simple rule; aim for your last exhale to be followed by only one word… “wow.”

JOHN:

Right on. You and Steve Jobs.

NORMAN:

That’s it. You should really aim to live a life where on your last breath you just go, with a big smile, “wow.”

I think every single person on Earth, without exception, lives every minute of their lives by their relationship with death, and what they think death is. If you think death is this final, then it informs everything you do that way. However, I think of death as nothing more than the end of a ride and I’m still inside the amusement park. For me, this moment right now is just the ride.

That’s a leveler. A way of becoming neutral, grounded, an observant and a participant rather than an emotional, reactionary beast. I can be emotional, of course. After all, I’m having a human experience. But the older I get, the more neutral I am about the state of things.

Breadfolks produce // 📸: Norman Jean Roy

JOHN:

You look very trim still, which you always were. Doesn’t owning and running a bread shop put weight on you? And how much bread do you eat, yourself?

NORMAN:

No. I mean, I eat bread all day long. That’s all we eat. It’s great. Chocolate croissants, you name it, I eat it. But I also average, on service days, around 20,000 steps. It takes seven hours. And I move fast. I’m not like a shoe shuffling kind of guy.

JOHN:

What about traveling? Do you miss that at all?

NORMAN:

No. Not at all! I have traveled over six million miles with American Airlines alone. If I never step foot on a plane, ever again, for the rest of my life… I would be very happy!

Breadfolks, Clayfolks and Roastfolks produce // 📸: Norman Jean Roy

ALISON:

Do you miss being on set or taking pictures? Or editing? Anything on the more creative side?

NORMAN:

I’ve definitely had moments… I had a moment not that long ago, where I told Jojo, “I really miss it.” And I think it was just because I was tired, I was just so tired.

There’s no arrogance in saying this, but I miss being really good at my chosen craft. I have such a deep knowledge of photography and sometimes, I miss the ease of doing something really well. Baking is still so new for me, so it’s very difficult. I don’t have enough knowledge yet to have the same kind of ease I had with photography. So, I’ve had so many moments of just going, “I just want to go do a photo shoot!” just so I feel like not such a f*** up, you know?

L, Alec Baldwin for Vanity Fair; R, Amy Adams for GQ // 📸: Norman Jean Roy

ALISON:

It is fascinating. Because I think lot of people would like to do it. But it’s frightening as well. You have to have a lot of courage to do what you did.

NORMAN:

I don’t know if you have to have courage or if you need to lack fear. I think it’s a very a different thing. For me, courage is the suppression of fear. Whereas, lacking fear is absent of suppression. When fear is absent from you life, you don’t see obstacles. To me, obstacles and problems are nothing but unsolved equations.

Fear is nothing more than a perception of something that has not happened. You’re everywhere but here.

I mean, it got ‘scary’ for us plenty of times. But I kept telling Jojo, “It’s like I have lost control of my legs and my body is walking me. I can no longer tell it to stop.” The best way I could describe it is like running towards a cliff without slowing down. Somehow, if you really are willing to run off the cliff, the cliff moves with you. It never lets you drop. But, you’ve got to be willing to do it blindly.

I told this recently to someone who was really struggling, ”Find that thing that would make it worth living out of your car, then you’ll know what you’re supposed to be doing.”

Breadfolks produce // 📸: Norman Jean Roy