I was very heavyset kid. You would call it clinically obese today. I grew up in a very loving Italian home, full of laughter, so it wasn’t something to be ashamed of. ‘He’ll grow out of it,’ they’d say. Then as soon as I hit the street, I got ridiculed. But being the son of a Marine, I knew how to stand up for myself.

At aged 12, I was walking a dog, a black labrador called Benji, for a neighbor in Foster City, Northern California, and there was a biker gang, all high on PCP and hallucinogens. Benji, who I loved, got off the leash and they hurt him real bad, and I had to pick him up and carry him back as he could barely walk. So after I dropped him off with his devastated owner, I grabbed some lighter fluid, a couple matches and I went and lit their motorcycles on fire. Being a heavy kid, I couldn’t move too easily, so it didn’t take them two minutes to catch me, throw me in the back of a van and take me to a little place where they camped out. I was tied to a tree and brutalized for three days.

When they finally found me and put me in hospital, my brother Joseph, who was five years older than me, and I decided to tell my mom and dad that I fell off the mountain on a camping trip. Then the following year, my brother — a brilliant athlete, brilliant student and amazing man — was killed on his motorcycle by a drunk driver. He was the only person who knew what had happened to me, and that died with my brother.

And I’ve since learned, through working on myself and by working with other addicts and trauma sufferers, we are only as sick as our secrets.

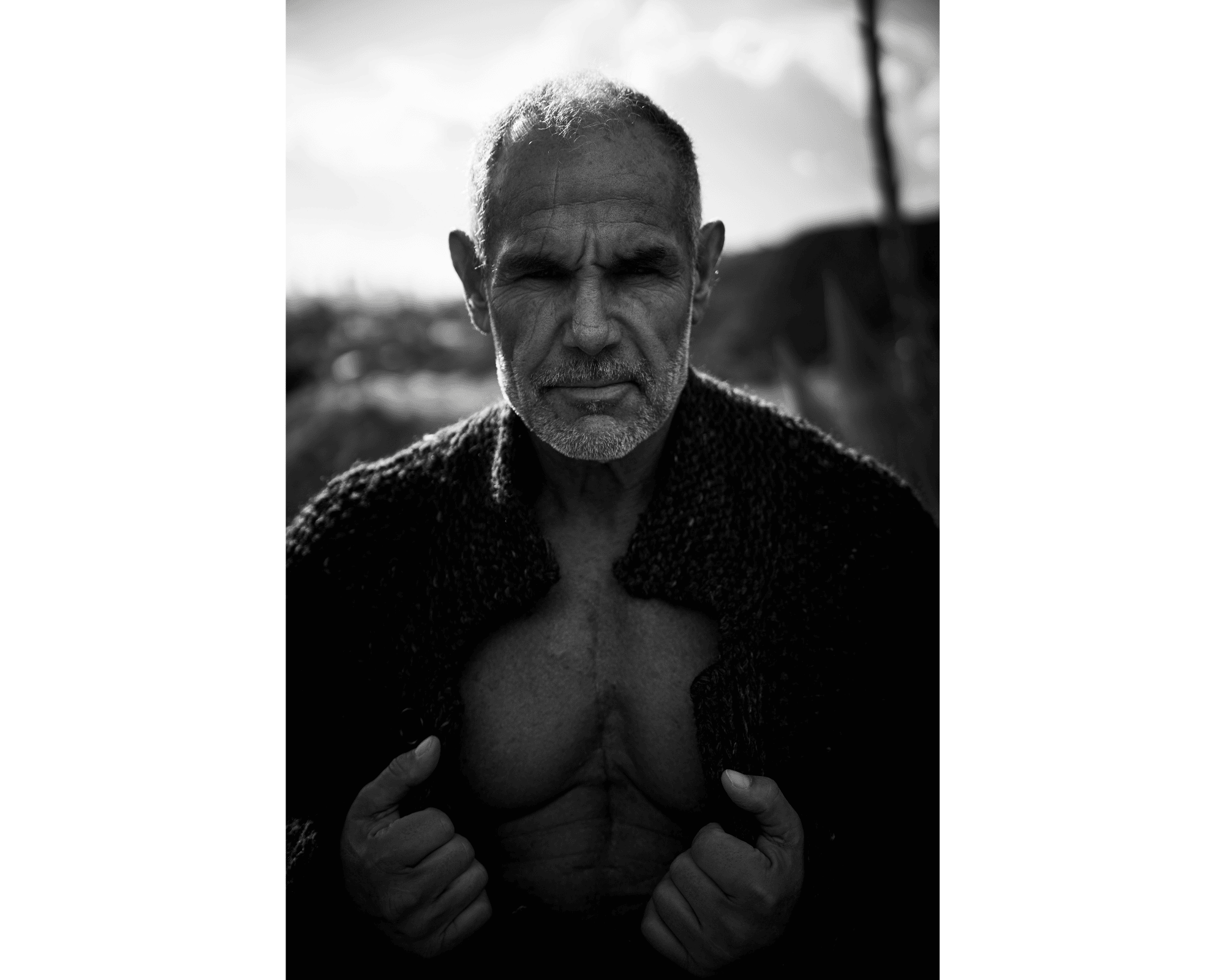

Jimmy Franzo // 📸: Kurt Iswarienko

For a couple of months after my trauma, I’d talk very little and was spinning from what had happened to me. I was already very heavy, probably 225lb at 5ft 6in, and I ballooned to 310lbs. Eating was my drug, my fix, my comfort zone. Then I met a girl, from another school, and she walked on water as far as I was concerned. I finally worked up the courage, and asked her to my junior prom. And rather than demean me or belittle me, she said, “Sweetheart, you’re handsome, you’re charming. I really like you, but you don’t take good care of yourself.” So that summer, I dropped 105lbs.

I was almost 18 when I left home, and I was walking around San Francisco when I got asked to go to a casting, and ended up getting my first modeling job in a little local commercial. And suddenly, I’m a model. I traveled to Paris, Milan and Greece and made some decent money. I then went to New York to visit a girl I met in Paris, I was probably 20, and I met Ian Schrager who owned Studio 54. I started working in the clubs, just as a meat opening the ropes, but I caught on fast and started working in the best clubs around town. New York just sucked me in. Then I headed to LA, initially for a two-night security job escorting some high profile folk for a party at the Playboy Mansion, before deciding to relocate to the city, and meeting the lady who would become my wife. That was four and a half years of being settled. I got married, was devoted, got a real job. I started fitness training people and doing the odd bodyguard job, and our kids, two boys, came one on top of the other.

Jimmy Franzo // 📸: Kurt Iswarienko

But after that marriage broke down, I ended up in South Beach, Miami, running the door of one of the hottest bars, called Rebar. It was crazy times, letting off steam after my marriage. As ever, I arrived in Miami, landed on my feet and hit the ground running. For eight months it was all business and it seemed like everything I touched turned to gold, by no genius of my own, rather simply being in the right place at the right time. South Beach was just about to boom and I was there to catch the wave. I became a partner and doorman at another of the city’s best nightspots, Velvet. And then I realized I was a high-functioning drunk. Soon after, this little thing called ecstasy was introduced into the mix. It helped me to be around my clientele and I started doing that pretty regularly, because South Beach was at its apex, and we’re open seven nights a week. Then about a year into doing this, I had started getting a tick, a twitch, and it started getting worse. So one of my buddies, the biggest promoter down there, gave me some heroin and said, “This will relax you, smooth you out.” I didn’t want to look stupid in front of him, and there were girls in the room, so I took it. It was like I was freezing cold my whole life, and someone finally put a warm blanket around me said, “Everything’s going to be OK.”

For a long time, I didn’t realize I had a habit. I didn’t realize I was a junkie. I functioned. I was still exercising like a madman. My experience with drug addicts and alcoholics is that we’re usually the last person to understand how bad it has got. But the thing is, I was killing my heart. And that was the beginning of a five-year downward spiral. I just couldn’t, as they say in recovery, surrender. Thankfully, I have a couple of really solid friends that were like, “You’re f****** up, pal. You’re not yourself.”

Jimmy Franzo // 📸: Kurt Iswarienko

I got myself clean and then, in 2013, I was caring for my dad in Los Angeles — bathing, shaving, dressing him — when my heart problems really hit me. I’d had shortness of breath, I had been dizzy, I had felt weak, but I also had built up a high pain tolerance and had so much experience simply pushing through because I needed to be some place. Today, I’m learning a little bit about boundaries, to say, “Hey, I’m not feeling so great. Can we put this off for a few days?” That would never be me before. But that day, all of a sudden, I’m changing my dad’s diaper, and I couldn’t breathe. And two hours later, the doctors told me, “You have advanced stage four cardiomyopathy and we don’t know how you’re walking around.” I was told that I had possibly two or three weeks to live, tops.

I go from fear to angry very quickly. I was disgusted with the doctors, “Who the f*** do you think you are? You’re a human being. OK, you’re a doctor. You went to school. But you can’t tell me that I have two weeks to live. I need to be here. I have two sons. My father’s dying. My mother has got nothing and no one but me. Give me another answer.”

I did not tell anybody, not my mom, not my dad, and went to find a second and third opinion. They all confirmed the first diagnosis. A few weeks later I realized I couldn’t walk up the stairs to my condo, I couldn’t see properly, I wasn’t sleeping well, I was breaking out in sweats, I couldn’t hold food down. And I started losing weight rapidly. I went from about 210lbs to 175lbs in six weeks. I was getting sicker and sicker and I was killing myself. I literally believed that on a cellular level, the secret was aiding the process of my body breaking down.

Jimmy Franzo // 📸: Kurt Iswarienko

I was on the transplant list for almost two years. I had an artificial heart that I was wearing, 7lbs of steel and plastic in a fancy little fanny pack that failed on me a number of times. I was six years clean when I got my heart diagnosis, but then I started abusing the opioids, Dilaudid, I was being given by the doctors following my surgeries. I was not in a good emotional state to make the right choices and the opioids had woken up the 300lb ape again. My heart stopped six times during that time. I collapsed in Whole Foods, then in the gym, and then on the beach. Wanting to be transparent, I admitted to doctors I’d been abusing the medications they had given me, and they came in a few hours later with paperwork saying I’d been taken off the transplant list.

Then one day in hospital, in March 2015, I pulled the cord out of the machine that was keeping me alive. I just wanted it to stop and death felt like an amazing reprieve. I didn’t care what was next. The buzzers went off and the next thing I know I had all the clinicians around me and they had started me up again. And that’s when I had a moment of clarity. That’s when I finally found acceptance and surrender. About whether or not I was going to go be with my dad who had just died, and my brother and many of my friends that passed, or if I was going to get a heart and live. I now had a plan for all of the scenarios. The plan is you live by every single day and try to make the best of it — and I hadn’t been making the best of it.

I sobered up from that point. I went on a cold turkey two-week detox that I wouldn’t wish on anybody. And I found a mentor who told me, “Do you want to go out like a dope fiend, or do you want to go out with some honor and with your sons’ respect and your mom’s respect?” Then a miraculous series of events took place. I showed up at the hospital every week, looking better, having a great attitude, being positive. And after four months, they put me back on the transplant list.

Jimmy Franzo // 📸: Kurt Iswarienko

On August 22, 2015, I got the call from this nice secretary at the hospital, who says, “Mr Franzo, we have an organ donor offer for you. How quickly can you get to the emergency room?” I said, “I’ll be there in five minutes.”

Someone had to die for me to live. I found out that he was 41, that he was a competitive cyclist and he had two young daughters and he was an honorable man from Sevilla, Spain. So now we’ve got the issue of, “Am I worthy?” And up until that point in my life, I didn’t believe I was. And then God — or the universe, or whatever you’re comfortable with — says, “Here’s somebody, else’s heart. I’m sacrificing their life. Their family will mourn them. Their time here is over, so you can go on.” So I knew I had some work to do, I needed to give back, to make my life a homage to this most insane bestowment.

I have been a volunteer on the heart transplant floor of a Los Angeles hospital for the last four years, and the comfort and encouragement I can give people waiting for a donor is one of the most fulfilling joys in my life. I also work with addicts and those who have suffered trauma in their lives, and created the men’s group, the Break True Camp, for men to support one another to find and express who they truly are. This is the purpose for which I believe I am still here. My job is to be a safe space for anyone who sits opposite me.

Jimmy Franzo // 📸: Kurt Iswarienko

When I’m doing a one-on-one with one of those men, who is sharing their secrets with me, who has come to that invisible wall where they don’t want to talk anymore, I can use my experience. And my experience tells me that in those moments, when we choose to be vulnerable, to release ourselves from our secrets, we can reach the next level of freedom and fulfillment.

True vulnerability is my strength, is your strength, is anyone’s strength. And I just think that’s a universal truth. If I had a mantra, it would be. ‘Holy s***, this is not going to be fun. But let’s move through it.’ Every ounce of pain and suffering that I experienced, I wouldn’t trade any of it. It’s all necessary for me.

I’m impeccably clean now, very little sugar even. I’ll have a cheat meal a couple of times a week and I’ll have a piece of cheesecake on my birthday. I get a green giant juice with beets every single day, and I know every kid at four different Whole Foods.

I started taking salsa classes six months after my transplant, before I found out my donor was Spanish and loved salsa, and my teacher said after my first class, “You must have done this before, you’re a natural.”

And I’ve always loved a sunrise and a sunset, but never like I do now.

Jimmy Franzo // 📸: Kurt Iswarienko

Learn more about Break True Camp here and follow Jimmy on Instagram @jimmyfranzo