Journalist, writer and editor Jay Fielden has met everyone. From politicians and novelists to rock stars and Oscar winners, his career trajectory has taken him deep into social circles that most of us can only imagine by reading his words. As noted for his impeccable sense of style as for his classically biting wit, Fielden has certainly left his mark on the New York literary world.

Born and raised in Texas, growing up with a love of magazines and writing heroes such as F Scott Fitzgerald and JD Salinger, Fielden moved to New York after graduating from Boston University, where he landed a job as a typist at the New Yorker, in 1992. Over the next eight years, he worked his way up the editorial ladder, editing pieces by the likes of heavyweights George Plimpton and Edna O’Brien.

In 2000, he jumped to Vogue, most notably as founding editor of the short-lived but much loved and influential Men’s Vogue, which, like many other Condé Nast magazines, closed in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, after four years.

In 2011, Hearst named Fielden editor in chief of Town & Country, where he took on the task of modernizing a dusty elitist society magazine with his uniquely intelligent and buzzy take on the modern-day hierarchies of the American social scene. His five year tenure increased revenue by 46 percent by appealing to a fresh male readership as well as retaining the long established ladies-who-lunch crowd.

In 2016, he switched floors at Hearst Tower to edit Esquire, known as a writer’s magazine and seemingly the perfect and logical match for Fielden, marking a return to more serious and sometimes controversial journalism, combined with covering fashion and menswear. His triumphant run was cut short however, following rumors of a rift with Hearst president Troy Young (who resigned in 2020, following allegations of inappropriate and toxic behavior in the workplace) and amid reports that Hearst executives had, against Fielden’s wishes, intervened to kill an investigative story on sexual misconduct accusations against director Bryan Singer — commissioned by Fielden and two years in the writing — which was eventually taken up and published by The Atlantic in January 2019, causing Singer’s downfall.

Check out Fielden’s stylish and elegant — and, of course, tongue-in-cheek — Instagram exit photo in the pictures below, with a visual nod to Jack Nicholson and a tip of the hat to his moving on from legacy media, after almost 30 years in the paper trenches.

With new opportunities now in his sights, Fielden has since embraced the freedom of his unaffiliated life, living in Connecticut and writing for publications such as Airmail and The Wall Street Journal (his recent WSJ piece on Ernest Hemingway is a must read). Following a devastating fire at his home in 2009, he said that what it taught him as an editor was to stop hanging on to things “that would keep you from doing something dangerous.” For him, that dangerous thing might just be writing that book he’s been thinking about for some time but never had time to write, about, he says, “a kid from nowhere who betrays his past to be accepted by a culturally elite organization that itself turns out to specialize in betrayal.”

Here we ask Fielden the 20 questions that get to the heart of who we are, as the latest subject of our ‘Who the F*** Are You?’ profile, where he talks about no longer having a job that owns him, how an early encounter with Ralph Lauren spurred his love of clothes, and always trying to master something new.

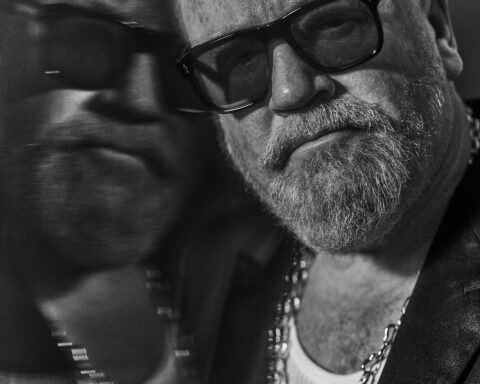

Jay Fielden // 📸: Laspata DeCaro

Who the f*** are you?

I met a mysterious woman once, a Christian who worked with the great theologian and writer Tim Keller, and she said to me, “You know what you are?” It was a rather direct thing to say two-minutes into a conversation. “A gatekeeper. You stand at the door, between two worlds.”

It caught me up short, like an epiphany. Here was this complete stranger putting her finger upon something I had always known to be true without ever having consciously realized it.

I’m a lot of other things. A husband to the wonderful Yvonne. Father of three crazy miracles. An editor, a writer. A Texan in Connecticut. A clothes horse. But above all, I think she’s right — I’m a gatekeeper.

How are you feeling right now?

I feel free for the first time in my professional life. From the age of 22, I’ve worked in magazines: The New Yorker, Vogue, Men’s Vogue, Town & Country, and, finally, Esquire. I don’t know how, but I somehow walked some pretty legendary halls. And I loved it truly, madly, and deeply. But those jobs own you, now more than ever, especially when you’re the editor in chief. It’s all you can think about; it’s all you want to think about. For the time being, at least, I’m very happy thinking about other things.

Jay Fielden in San Antonio aged 17

Where did you grow up and what was it like?

I was born in Odessa, in West Texas, a boom-and-bust oil town in the high desert. It’s a wild place where all kinds of people have gone hoping to make a fortune. About two years ago, I ran into George W Bush; his dad moved the family there in 1948, so I mentioned the connection. “Bullshit!” he said. Tony Blair was standing next to him. “This guy was born in Odessa, Texas,” he cackled. “Moving there’s one thing — being born there, though, that’s harsh.” He’s right, but we later moved to San Antonio, and that’s where I really grew up. It’s a city that takes its architectural character from Spanish colonialism, its food from Mexico, and some of its street names from settlers who were German. It’s got a mixed, old-world heritage, and, unlike Dallas or Houston, is less flashy. As it turns out, it had one of the first, stand-alone Polo Shops. In high school, in the late 80s, I got a job there. As far as American taste goes, I still consider Ralph the top.

Jay Fielden at the New York Conde Nast offices in 2005 as he worked on Men’s Vogue’s first issue // 📸: Pascal Perich

What excites you?

I’m a learner. I hate to be nagged by things that make me feel dumb or lazy for not knowing, so I’m always trying to master something new.

I got to know Harold Bloom in the last years of his life. “Reading is a race against the brevity of life,” he told me, by which he meant that knowledge enriches life, especially the kind of knowledge that’s unveiled in the great books by the great writers. When I remember that, I feel pretty guilty, even embarrassed, to have spent as many hours as I recently have watching “The Walking Dead.” That’s why one of my favorite mottos is from Thoreau, which goes something like: “Just because I don’t do what I say doesn’t mean what I say is wrong.”

What scares you?

Boredom terrifies me. I think it is a glimpse of the underside of eternity. It’s evil in the sense that if you’re bored, you’re not doing or creating or providing what you’ve been called to do, create, or provide. It’s a signal, like hunger, that you need to fill that hollow feeling with something substantive and good, not frivolous and cheap.

Jay Fielden // 📸: Laspata DeCaro

What is your proudest achievement?

I recently wrote a piece about Hemingway for the Wall Street Journal. That was very hard for me, as I’ve felt, like so many writers have, as if the guy’s been sitting on my shoulder my entire life. There were more times than typical while I was writing it that I just wanted to believe some excuse in my head and give up. But I didn’t. I said my piece. And I’m proud of getting all those thoughts, banging around in my head all those years, down on paper. It was, as my late friend Robert Hughes once said, “like squeezing glue through a sock.”

What is the hardest thing you have ever done?

We had a house fire in 2009 that destroyed almost everything we owned. My wife and I, and our three kids, walked out in our socks and had to rebuild our lives again from there. It was terrible, horrific, though it was, as we discovered, also liberating. You don’t really want to find this out, but you can live without your stuff. You own it, but it owns you, too

Every once in a while, I’ll be looking for something — a book, a tie, a memento from some trip — and I’ll realize that the reason I can’t find it is because it was lost in the fire. The moment is always more than a little painful, but it’s important not to forget.

Actor Daniel Day Lewis on one of Fielden’s favorite Men’s Vogue covers, February 2008 // 📸: Mario Testino

Who was your greatest mentor and what did they teach you?

I tell every young person I know to find a mentor. It’s so important. I had many, so very many, and I still do.

This might be a funny way to answer, but I was speaking to a friend, a very accomplished guy who recently stepped away from a big job, kind of like I did, and who also got there in an unlikely way. He asked me once what my motivation was back then, in Texas, that made me believe in the dreams I had. I told him I didn’t really know. I just kept pushing myself. “Thank the young Jay for that,” he said. That was very good advice. I’ve since looked back on myself as a kid who didn’t know much, and I’ve learned a lot from him.

Who are your fictional and real-life heroes?

Let’s stick to real life for the moment: I play a lot of tennis and Arthur Ashe is someone who I find to have been a remarkable, inspiring man. You want to look at two amazing examples of what it means to be a dissident? Read up on the anti-Nazi Christian theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer and the anti-communist Aleksander Solzhenitsyn. The journalist Glenn Greenwald strikes me as very brave, and I think Ricky Gervais has guts and is hilarious. Tulsi Gabbard also speaks her mind, a courageous thing to do these days.

Actor Lily James on the March 2016 cover of Town and Country, an issue in which Fielden’s two daughters Clara and Eliza also appeared // 📸: Lily James by Vincent Peters, Clara and Eliza by Max Vadukul

What is your favorite item of clothing in your wardrobe?

Right now? A pair of burnt orange Champion sweatpants by Todd Snyder.

What music did you love aged 13 — and do you still love it now?

Duran Duran — and I’ve never stopped loving the music. I thought John Taylor was — and is — the coolest. Great musician, great guy, great style.

Jay Fielden // 📸: Laspata DeCaro

What is the most inspiring book you have ever read?

Man, really? It’s like asking me to choose my favorite child. Impossible! But I’ll give it a shot: ‘The Brothers Karamazov,’ by Dostoevsky. It took a while, but when I put it down, I genuinely thought, why did anyone ever try to write another novel after that?

What is a movie that left a lasting impression on you?

‘A Room With a View.’ I still love it. I don’t think there’s one weak moment in it, and it stands up to watching again and again. One of my favorite scenes is when Daniel Day-Lewis, playing Cecil Vyse, says, “There are some chaps who are no good for anything but books” about the time he gets hit in the head with a tennis ball.

Fielden’s final Esquire cover, featuring Brad Pitt, Quentin Tarantino and Leonardo DiCaprio, Summer 2019 // 📸: Alexi Lubomirski

What is your favorites word or saying?

Julius Irving once said, “Being a professional is doing the things you love to do on the days you feel like not doing them.” I keep that tacked to my office wall–and tattooed on my brain.

What do you want people to say at your funeral?

I’ll be looking for you when I get to the other side.

Fielden’s tongue-in-cheek exit photo from Hearst, with Jack Nicholson as his inspiration

And finally, a quickfire five favorites …

Car?

1965 Aston Martin Volante. Green, please, with saddle-leather interior, and deployable outrigger skis.

Sports team?

Football: Dallas Cowboys. Basketball: Baylor.

Meal?

A Chianina bistecca and bottle of Siepi, at Sostanza, in Florence.

Grooming product?

I sample a lot of things, but I’ve been sticking with this for a while: Kiehl’s exfoliating Daily Cleanser followed by Acqua di Parma Essenza face lotion.

Clothing label?

Jay Fielden // 📸: Laspata DeCaro