When Rupert Isaacson was told his two-year-old son, Rowan, was severely autistic, he reacted as most parents would. “Nothing prepares you for becoming a special needs parent,” he says. “You never think it will happen to you, and when it does, it’s like, ‘F***! What do I do now?’”

One in 54 children in the US are diagnosed with autism, and Rowan was level three on the three-tier spectrum, with these sufferers potentially needing lifelong care. Rupert says he first bounced between “fear and denial,” worrying he might never be able to communicate with his son, who he was told could be “unreachable”, and struggling to come to terms with the challenging life his helpless, blameless boy now faced.

But what Rupert did next was far less typical, in fact it was quite extraordinary. He took his son to Mongolia, in East Asia, to traverse the rugged terrain on horseback, in scorching heat, and visit a series of shamans. And that trip was just the start of an incredible journey that has led to Rowan and Rupert both flourishing in their lives. Rowan, now 19, is self-sufficient and attending a regular high school, preparing to go to college and study abroad, while his father is sharing what he has learned from his son with thousands of young people and educators around the round.

Rupert explains, “Very early on, I had this question pop into my head, ‘What if this is the best thing that’s ever happened to you?’ And if so, what does that look like and what does that mean?”

The father and son’s adventure began when Rupert visited the scientist and activist Temple Grandin, a bestselling author, professor of Animal Science at Colorado State University, and one of the world’s leading voices in the field of animal rights, who is herself autistic. With Rowan still an uncommunicative, incontinent preschooler at the time, Temple shared with Rupert the fundamentals of what would shape his son’s education, and the father and son’s lives.

Rupert explains, “I literally said to her, ‘How does my son become you?’ And Temple said, ‘It’s relatively easy. You’ve got to follow the child. And that meant three things, you’ve got to follow him physically, because he’s not verbal, so he’s not going to say, I want to watch his TV show, or I want to play with that toy. He’s just going to do it. You’ve got to follow him emotionally. You’re going to notice very quickly, that there are times when he seems inexplicably sad, and times he seems inexplicably happy, and you’ve got to try and notice what seems to trigger one or the other. And the third thing is you have got to follow him intellectually. Follow his interests and really go with that.’

“And she did give me a clue, she said his interests were likely to be about nature. In general, autistic people have highly over sensitive nervous systems, and in nature there are very few bad sensory triggers because the human sensory system is designed to be outside.”

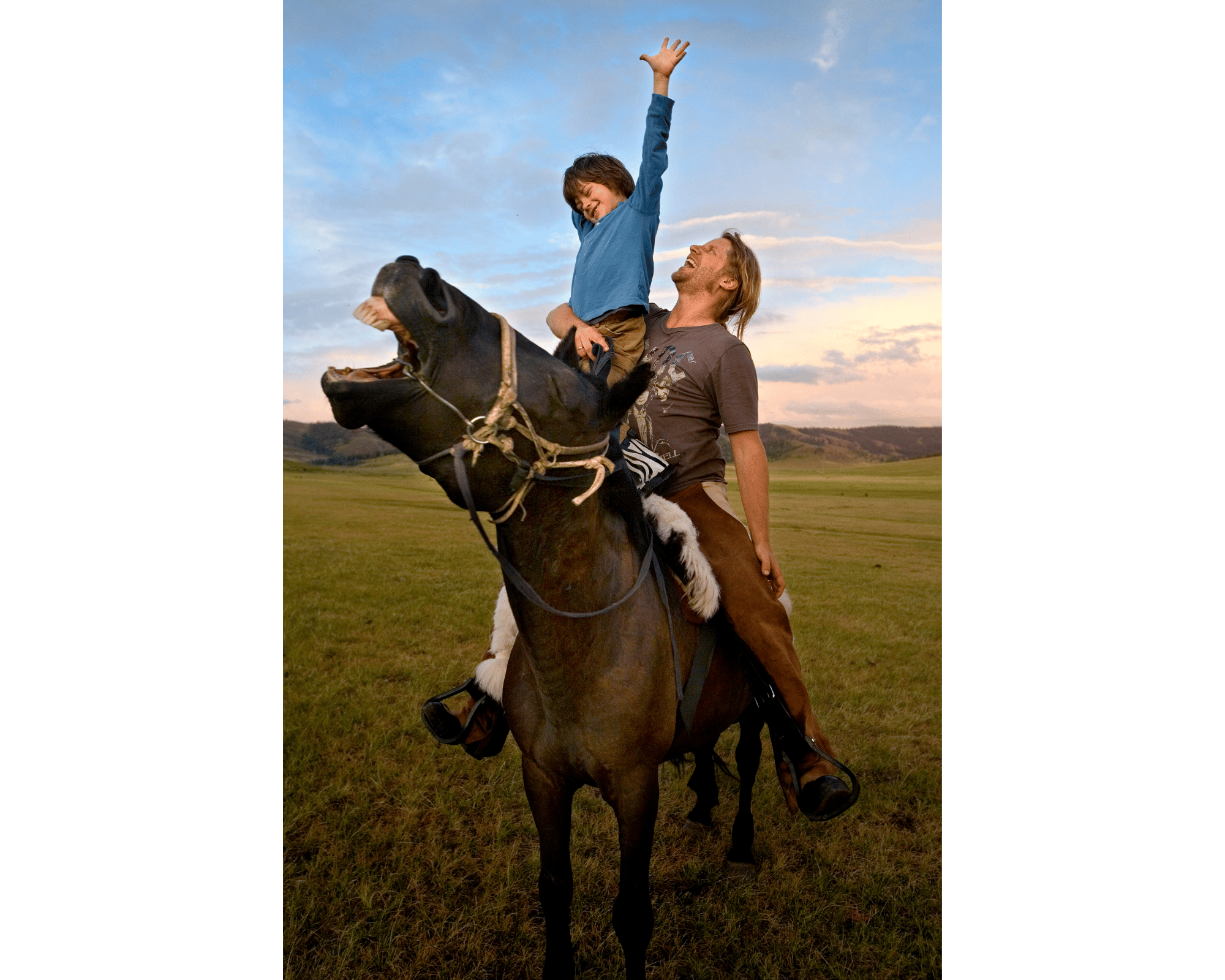

Rowan’s passion for horse lives on today

So from that day forward, it was Rowan who led the way in the pair’s adventure, which brought huge opportunity and fulfillment amid the challenges they faced. Previously, Rowan had been struggling to settle in his traditional autism therapy, called Applied Behavior Analysis, so inspired by Temple’s advice, Rupert let Rowan, then three years old, decide their next direction.

“I saw that he wanted to get out of the door,” Rupert recalls. “So I opened it, and he went into the woods behind the house. Immediately he just wanted to put stuff in his mouth.

“I didn’t want to say ‘no’ and discourage him, so instead I went online and looked up the edible plants in my area, and we started foraging together. Immediately we had communication, adventure, exploration and science, and to this day he can forage his own wild foods.

“It was then that he saw my neighbor’s horse, Betsy, and headed straight for her. What was strange was I’m a professional horseman with decades of experience, and I was keeping my son away from horses because I thought it wasn’t safe. But when I put him on the horse I noticed all of his agitated behaviors went away. And then the first day I rode with him was the first day I got proper speech. We were riding towards the pond and a heron got up and flew away, and he said, ‘Heron.’ I had no idea he knew that word, and it was a hell of a word to come out with.

“I noticed very quickly that I got more communication when I went a bit faster, and I also noticed that the more rhythmic I make the horse’s movement, the more communication I got.”

Rupert continued to build on his son’s love of nature and horses as the basis of his education and development over the coming years. Rowan learned to read from letters painted on trees in the woods near their home in Elgin, Texas, and learned to count from the horse’s footfalls. But Rupert had an urge to follow his son’s passions even further afield. A British-born journalist of southern African descent, he had extensively covered human rights stories surrounding the Bushmen in Africa, and was deeply affected by their way of life.

“I had done all this human rights work with the Bushmen of the Kalahari, in South Africa, Botswana and Namibia,” Rupert explains. “Those people are probably the most functional human beings on the planet, and they’re also the oldest culture on the planet, so they’re sort of the blueprint. I was interested in how they parented. Also, it occurred to me that a lot of the good healers that I knew in the Kalahari seemed autistic. And these people, who were like my son, were at the center of their society.

“But Africa is not a horse culture, and Rowan was really into horses. So I thought, ‘Where is a horse culture with shamans? Where does the horse come from?’ That’s Mongolia. I just had a gut feeling we had to go there.

“We did this crazy f****** trip, traveling from healer to healer, and it was incredibly hot. We were looking for a healer called Ghoste, who I knew about but wasn’t sure if we would find, but we did. And then 27 hours after the healing, which unfolded over three nights, Rowan did his first intentional poo and cleaned himself. And we went home with completely different kid.”

Rowan in Mongolia // 📸 : Justin Jin

The trip to Mongolia, where the father and son also traveled with Rowan’s mom, educational psychologist Dr Kristin Neff, was documented in Rupert’s documentary and bestselling book, ‘The Horse Boy’, a decade ago. And on the advice of the Mongolian shaman, they then took three more healing journeys, to the Bushman of Namibia, to Australia’s coastal rainforests and to America’s Navajo reservation, in the coming years, which Rupert wrote about in his next book, ‘The Long Ride Home’.

And back in Texas, Rupert now had groups of other autistic children coming to their ranch, and discovered they benefited from these methods of incorporating rhythm and nature into their education as well. He started to speak to neuroscientists around the world to find out why these methods were working, and was told that one of the issues in the autistic brain is an overactive amygdala — the part of the mind that controls our reaction to stress — which causes sufferers to produce extra cortisol which prevents them from learning. But rhythmic motions, like those Rowan enjoyed on the horse, can produce a contrasting hormone called oxytocin, which can improve happiness and communication. And movement also promotes the production of BDNF, a protein which helps to regulate synaptic plasticity in the brain and is important for learning and memory.

Rupert soon launched the Horse Boy Foundation, to help those with autism, trauma, anxiety, learning disabilities, PTSD, and other neuro-psychiatric condition to receive access to alternative education that could aid their development. And now that has grown into the New Trails Learning System, which is connecting educators and young people from all walks of life, not just those with special needs, with the lessons Rupert has learned about the powerful role movement and nature can play in education.

He explains, “It’s beyond autism now. There are lots of schools that are taking on this Movement Method, as we call it, as their regular way of teaching.

“We are working in about 30 countries and serving about 200,000 to 300,000 families. And we’ve adapted the national curriculum in Germany, the UK and US to be taught through movement. Even in a classroom with 30 kids and one teacher.

“We change the layout of the classroom and allow the kids to circulate where they’re sitting. They can get up and move at any time they want to. We have different types of seating, some revolving chairs, some rocking chairs, some yoga mats on the floor. And we teach science and maths by using the body.

“We are also changing the environment and bringing in natural objects. Your body is supposed to interact with wood, with stone, with sand, with plants. We’ve literally started putting trees inside the classroom.

“And these principles can apply to everyone. If you have a horrible row with your wife go for a walk for half an hour in nature. Get that BDNF and then you can think again and have a new perspective.”

Rowan drives his father home in Texas last month

Now Rowan travels the world as one of the ambassadors for Rupert’s work, which, of course, Rowan has really led from the start. And he’s helping his old man out in other ways too.

Rupert says, “He’s at high school and he has his own car, his own life. He likes history and art, he’s better than I am at maths. He’s starting to talk about community college and probably studying abroad.

“He’s still very quirky, he’s definitely autistic, but also so functional. A few weeks ago, we went out in Austin together to meet some friends, and I had a few beers so told him he was going to have to drive.

“So we’re on the freeway heading back to the farm, and I’m looking at him from the passenger seat going, ‘F*** man! You used to be non-verbal and incontinent. And now here am I, non-verbal and incontinent, and you’re driving me home!’”

The last 15 years have affirmed that thought that came to Rupert at the very start of this journey, that his son’s condition could be a blessing and not a curse. And he now hopes that Rowan and other autistic individuals will be able enrich the lives of others like they have his.

“Their ego is very much in the background,” he says. “I’ve had to do 30 years of rigorous spiritual practice to even possibly get a little bit past my ego. They’re born with that. They just don’t compare themselves to other people.

“So do I think that these people will pull us out of the s***? I think so. I mean, look at people like Greta Thunberg, she’s autistic. It’s these people that they have a capacity to look for solutions that we might not see.

“And they are dream whisperers. I’d written a few books before The Horse Boy, but nobody read them. Only when I put my writing into the service of my son and people like him did it take off. If you devote yourself to the service of people more vulnerable than yourself, your own dreams will start to come true. I believe that is the secret of happiness.”